|

→ August 2007 Contents → Column

|

|

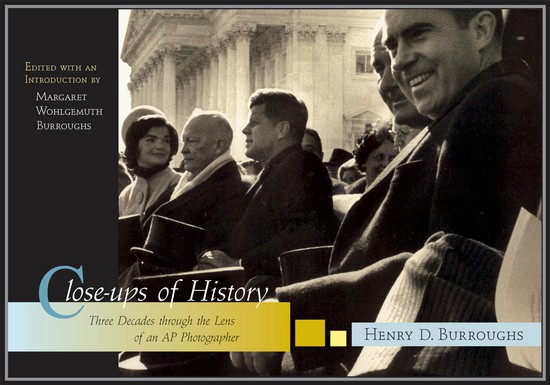

"Close-ups of History" by Henry Burroughs University of Missouri Press, 2007 240 pages, illustrated. A Shooter:

Henry Burroughs August 2007

|

|

Citizen journalism and citizen photojournalism are today both the flavor of the month. A person is not a photographer, however, just because all he or she does is turn on a cell phone, point and shoot. But these days, image, no matter how poor, seems to be all that counts. Quality means almost nothing. It was not always that way. It took training and an apprenticeship to become a photographer. For those who really aspire to be photojournalists, it still does, and still is the way to success. The book I am about to describe, Close-ups of History: Three Decades through the Lens of an AP Photographer by Henry D. Burroughs, is a book for all budding photographers in this digital age who will never pick up a camera that uses film. Henry Burroughs' memoir, in some ways, is a last march down memory lane by a man proud to be nothing more, nothing less, than "a shooter."

I have known many photojournalists who thought of themselves as shooters first. Usually they were faceless men and women who worked for photo agencies, newspapers or magazines. I saw them everywhere in the world covering events as they unfolded, anxious to get that one shot that might make the front page, or, if not, at least a place somewhere else in the newspaper or in the magazine. We should not forget that print was once a force in our lives despite today's rapidly changing landscape. These "shooters" were not artists. They were journalists with cameras covering events large and small as they unfolded in front of their lenses. These men and women still exist, but today the camera of choice is digital; their means of getting their pictures where people can see them is a laptop and entry onto a satellite. But what they do and how they do it is the same. Their job is to get the best shot they can to entertain, inform, and even shock an audience.

Henry Burroughs had the reputation as a photographer who "always came back with the picture." The picture! What makes a good picture? According to Burroughs, it's "a good photographer with lots of luck and good timing. Instinct and keen sense for the news play a great part also to capture the moment."

Burroughs started in the business of making pictures in 1935 in Baltimore at the height of the Depression. After graduating high school he needed a job and found one as a photographer's assistant in a commercial studio for eight dollars a week, not a bad salary in those days. He learned how to process film, how to light, how to shoot. After his job ended a year later, he went to work as a photographer at the Washington Post in advertising and promotion, not in news. In 1944, he learned about an opening at The Associated Press as a war correspondent. Though he had the title, and was on the list for either Europe or Japan, he first worked in Washington and at the White House. Franklin Delano Roosevelt was president. There were only three wire services permanently assigned to the White House -- AP, Acme News Pictures and International News Photos. Other news organizations came and went as needed.

When World War II ended, Burroughs got his break and was on his way to Europe and what would be a 33-year run at the AP. He covered postwar Germany from 1945-1949, including the war crimes trails at Nuremberg, the Berlin Blockade and airlift. Covering Nuremberg was a cumbersome job. He used a big 5/7 Graflex camera, nicknamed Big Bertha, custom-built to carry a huge telephoto lens, about the only way to get shots of the trial because of where the authorities positioned the press. For normal coverage, he used a Speed Graphic, also a big, lumbering camera well before the mass use of smaller, more mobile equipment. Instead of just clicking to get a picture Burroughs recalls, "If you were really fast, it would take 7 seconds to replace the slide, turn the 4x5 holder, pull the slide, cock the shutter, and remove and replace the flashbulb. On a hot story, those 7 seconds could seem like a lifetime."

Soon Burroughs was back in Washington, assigned to the White House where over the years he covered Presidents Harry S. Truman, Dwight D. Eisenhower, John F. Kennedy, Lyndon B. Johnson, Richard Nixon and Gerald Ford. In 1972, doctors discovered he had cancer behind his left eye. He had treatment but says the treatment virtually destroyed the vision in his left eye, prompting him to retire early in 1976 when he started to find it impossible to be the shooter he had become.

Henry Burroughs died in 2000 before he could finish his memoir. Completed by his wife Margaret Wholgemuth Burroughs, it is chatty and enthusiastic, the story of one man's life as a photojournalist, an eventful journey through history from a man who says, "I had always been and loved being a shooter."

© Ron Steinman

|

Back to August 2007 Contents

|

|