|

→ August 2007 Contents → E-Bits

|

Ebits:

Black and White and Read All Over August 2007

|

|

||||

|

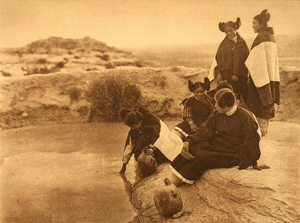

A correspondent who paints queried me the other day about color photography, saying that he remembers being ecstatic the day Kodachrome ASA 64 film came out because it made possible saturation of the blues and reds never achieved before. Then he pondered my age, suggesting that I was old enough to have started in black and white and the darkroom, which indeed I did. In fact, had it not been for the way black-and-white photography used to be and all that went with it in the old days, I wonder if I would have fallen for photography at all. The whole Brownie camera craze completely eluded me as a child. I couldn't have cared less about photography then, although I always did like to see snapshots, and loved our subscriptions to Life, Look and The Saturday Evening Post. It was not until I was 28 that I became betrothed to photography. I discovered Edward Curtis' North American Indians, bought a Nikkormat and a brick of Tri-X, and decided to leave my job as assistant to the publisher at Texas Monthly to take pictures. It was my leap of faith into the void, the setting sail into uncharted waters, or whatever else one might call such an embrace of the unknown and uncertain. One might also call it descent into the unconscious or glimpse of eternity, or some other similar term, but what it really was, was love. I fell in love with photography.

Because I was drawn to discover this world of the unconscious, I found at the same time an increase and requirement to be disciplined. I no longer had a time I had to report for work every day, nor anyone lording over me as a taskmaster, and I became my own boss -- artist, technician and publicist -- I was on my own in every way. It was expensive to have my film developed and prints were prohibitively costly so I settled for film developing and contact sheets only, but even that soon threatened my savings. I didn't have a clue how to develop film myself, so I called a photographer I'd known from Texas Monthly and offered to exchange work as an assistant for hanging around his darkroom. This fruitful trade prompted me to go to the lumberyard and plumber's supply to get enough materials to build a darkroom sink, and I took my credit card that had an $800 limit and charged it up half-way, buying an Omega B-66 enlarger, paper, chemicals, bottles, trays and a safe light. After two months assisting and observing photographer Michael Patrick both on the job and in the darkroom, I once again struck out alone in the wilderness to find out more about what had me completely infatuated and firmly in its grip: black-and-white photography.

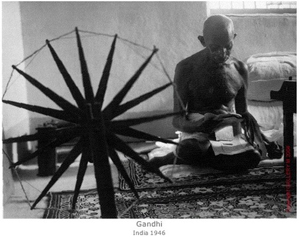

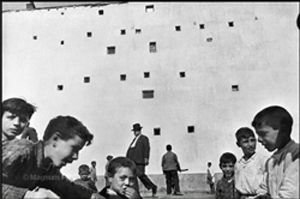

At the same time I started shooting and doing darkroom work, my new best friends became the Austin Public Library and the libraries at The University of Texas. At any one time I had at least 10, sometimes 20 books checked out, and I wore out my back and a canvas bag toting books from the library to my car, then from the car to my house. I spent all my free time voraciously reading every page, and more importantly, internalizing every image. I didn't give a hoot for color, don't ask me why -- I lusted after black-and-white photos. I couldn't get enough. My first heroes? Edward Curtis, Margaret Bourke-White, Henri-Cartier Bresson, Eugene Smith, Yousef Karsh, Eve Arnold. Karsh's Portraits and his Canadians were astonishing to me. They were printed on platinum paper, and the light in his photographs caused me to swoon as if I were looking at a Vermeer. I wanted to print like that. I wrote letters to Karsh and Arnold, asking for assistantships. I wanted to meet Henri Cartier-Bresson, and when I found out he started as a painter, I was nearly delirious, since I've always drawn or painted, doodled and illustrated. I shot during the day and printed at night, starting at 10 in the evening and going on until 5 in the morning. Every night. The wee hours were the quiet time in any 24-hour period. I could sleep anytime, but I couldn't get uninterrupted time except in the middle of the night, and the dark helped any bothersome ambient light in the darkroom. It was the most romantic time of my life. I ate, drank, slept, dreamt, talked, shot, developed, breathed and LOVED black-and-white photography and everything about it. The more I loved photography, the more I loved mankind, and became convinced that photography could save the world. Apparently that was not an original thought, but I didn't know that. It was my own personal discovery. I would save the world.

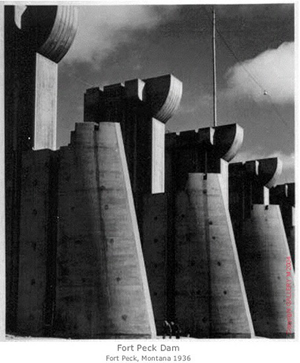

I was thinking big, but I was in a smallish town in Texas, nothing like New York, and did what I could think of here. Since I had worked in publishing, it was my good fortune to be hired almost immediately for various types of jobs. So I shot postcards and posters, portraits and weddings, advertising and food and landscapes and architecture, basketball games and the symphony. My boyfriend was a musician and I shot jazz and classical concerts and ballets and the circus. Whatever it was, I would try, and if whoever hired me didn't like what I did, I told them they didn't have to pay. Everybody paid and hired me again. I found I didn't care for commercial work, and I didn't care for setting up shots or studio lights or anything that wasn't real. I only liked available-light, candid, black-and-white, editorial photography. I soon dropped everything but the jobs I wanted to do with three lenses and available light, and before long I was getting newspaper and magazine work. I was so in love with photography. National Geographic was wonderful, but it was color. I realized I could never shoot for them because they wouldn't have me, though I admired the work of their photographers tremendously.

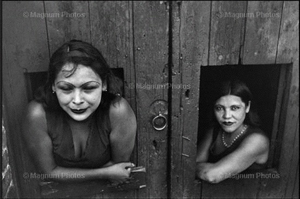

Beyond National Geographic, my heroes extended to an endless lineup of notable and great photographers, living and dead. Imogene Cunningham, Ansel Adams, Edward Weston, Minor White, Philip Jones Griffiths, Robert Doisneau, Berenice Abbott, Mary Ellen Mark, Arnold Newman, Diane Arbus, Edward Steichen, Alfred Stieglitz, Eugene Atget, Brassai, Julia Margaret Cameron, Paul Caponigro, David Douglas Duncan, Robert Capa, Carl Mydans, Walker Evans, Robert Frank, and later, Elliot Erwitt, Susan Meiselas, James Nachtwey, Sebastiao Salgado. I took workshops in Maine with David Burnett and Robert Pledge of Contact Press Images, and with Gilles Peress of Magnum. I attended photo conferences and met an enormous number of photo luminaries, but somewhere in there I became a cartoonist, keeping an illustrated diary when I wasn't shooting in Texas. Kodak hired me to record and illustrate Maine Photo Workshops' ambitious yearly International Photo Congresses, and we sent the journals I produced to all the participants. It was fun, and it was about photojournalism, but it wasn't doing, but thinking about photography. Art became a very important substitute, and pretty soon, I fell in love with that too.

I had become fixated on documentary photography, and I spent quite a bit of time – years in fact – fantasizing about being a war photographer. I thought I would be a good one. My mother was a heavily medaled, state champion riflewoman; my father had been a Marine in WWII, and our family was in the funeral business. I thought I had the compassion to cover suffering, and the funeral home had operated an ambulance service my whole young life, so there was always an emergency, or worse. What, really, that had to do with qualifying me to shoot war or the stories of the people in the Middle East, I'm not so very sure. I mean, where was I going to get the bravery? No matter -- I thought I'd worry about it when I got there. My friend who now paints beautiful watercolors worked as a journalist with photographer Catherine Leroy in Iran, and said she was a tiny stick of dynamite, bravely going out in front of the nervous journalists to get the story when all hell was breaking loose. If Margaret Bourke-White or Susan Meiselas or some tiny person like Catherine Leroy could do it, maybe I could too. I was free, and thought like Bobby McGee, I had nothing lose. For a while, I thought I would absolutely die if I didn't get to do international work. I didn't, on either count.

Eventually, I ended up going back to school in architecture at the age of 47. I thought I was giving up photography forever, and wrote my thesis, which later was published, about as big a thing as I could think of: the Ka'bah in Mecca. Just after I finished graduate school, I signed the book contract for The Ka'bah in August of 2001. Then, September 11th came along. Everything, everywhere changed, photography too. Since the mid-'80s, almost all photojournalism has been in color. I say the word 'almost' with great reverence and thanks to Sebastiao Salgado for his exceptional black-and-white work. Nowadays, photographers are embedded with troops rather than on their own in war zones, and more journalists and photographers have been killed in conflicts since 2001 than ever before. Dirck Halstead has for years been warning photographers they must know video journalism and be prepared to shift back and forth between still and video techniques. His Platypus Workshops – he's in Maine conducting one right now – are all about preparing photojournalists to shoot video stories. None of that is my cup of tea.

I still draw and I still shoot photographs, but I do these two things largely for my personal amusement. I carry a small digital camera, and I have it set on black and white, but I don't want to do war photography any more. Somewhere in there I fell in love with the written word, so now I write. I blog for Earth and Sky, the syndicated NPR radio show. I still want to save the world just like everybody else, but I don't know how. It doesn't seem that anyone else does either, but if somebody out there has any ideas, please send them our way. We are all ears.

© Beverly Spicer

The links that appear in this column are from the World Wide Web. Credit is given where the creator is known. The Digital Journalist and the author claim no copyright ownership of any video or photographic materials that appear herein.

|

|||||

Back to August 2007 Contents

|

|