|

→ October 2007 Contents → Feature

|

Capa and Taro:

Together at Last October 2007

|

|

|

They started on a journey together in Paris that would sadly end in her untimely death during the Spanish Civil War, and for him immortal fame as possibly the greatest war photographer who ever lived.

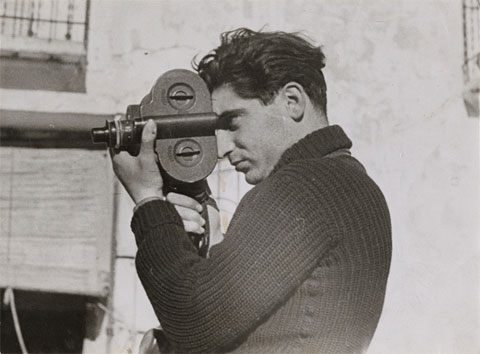

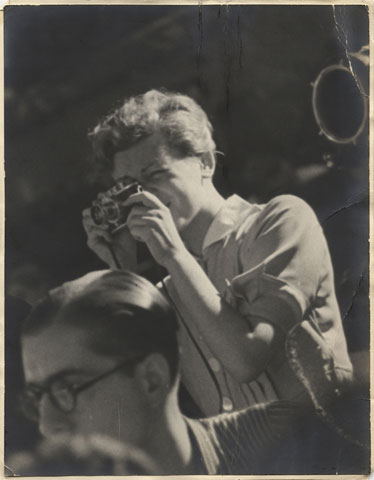

The work of Robert Capa and Gerda Taro, two remarkable photojournalists forever joined creatively and major figures in the history of war photography, is currently on view in separate twin major exhibits at the International Center for Photography in New York from September 26, 2007 through January 6, 2008. It is always important to see Robert Capa's work again. Here, in the exhibit called "This Is War! Robert Capa at Work," the photos and documents are from six important wars Capa covered between 1936 and 1945. These are: The Falling Soldier, 1936; The Battle of Rio Segre, 1938; Refugees from Barcelona, 1939; China, 1938; D-Day, 1944, and the Liberation of Leipzig, 1945. We see the photos and documents that are a testament to the power of Robert Capa's ability to see war, and the men who fight it, from a perspective few journalists then were able to capture, and from which many now still get their inspiration. However, this exhibition is different because for the first time it ties his work in Spain to that of his friend, lover and collaborator, Gerda Taro.

When the Spanish Civil War started on July 17, 1936, Taro, 25 at the time, and Capa, only 22, went to Barcelona to cover what for many was the military and political rehearsal for World War II. The Spanish Civil War? Here is a reminder of what happened. Fearing that Spain would become socialist, the army attempted a coup d'etat against the new government of the Second Spanish Republic. Elements in the military thought the government would crumble against the professional army, but it did not. Each side had its sympathetic supporters. Republic forces had the backing of the Soviet Union and, thus, believers in socialism, or communism, everywhere. Those who rebelled against the government and its followers had overt military and financial assistance from Fascist Italy and Nazi Germany. Fighting was intense and gory. The war dragged on for three destructive, atrocity-filled years, ending in victory for the Nationalists under General Francisco Franco. Gerda Taro and Robert Capa were both enormously sympathetic to the leftist cause in Spain, understandable because of their backgrounds. Both knew instinctively that they would have the opportunity to photograph war as it was happening, rare in those days in Europe. During the first days of the war, they often worked side by side, documenting the same action and events. Interestingly it is easy to see who took which shot because of the different cameras they used – Taro the "square-format Rollei and Capa the rectangular Leica." At first they published their photos together in major magazines that, under their mutual agreement, the magazines credited only to Robert Capa, but it was a collaborative effort only recently made clear from their contact print notebooks from the period. Looking at the notebook provides fascinating insight into not only how they worked, but also the attitude they brought to their work. What they photographed was sometimes startlingly similar, as if they had the same eye. They returned to Paris and after a second trip to Spain in 1937, they started publishing under the name "Capa&Taro." By then they were also both using the same 35mm format, thus making it more difficult to differentiate between their photos. At this time, Taro was also starting to publish her photos in the French leftist press. Her credit "Photo Taro" started to appear regularly in the left-wing French newspaper Ce Soir. Though their romance had cooled, their dedication to their profession and their ardor to leftist causes only grew, especially by Gerda Taro, seemingly more dedicated than Robert Capa. In Madrid, Taro had become part of the international community of anti-fascist artists and intellectuals, including Ernest Hemingway and John Dos Passos, who had also come to Spain to cover the war and protest its direction. After they made their second trip to Spain in early 1937, Capa stayed only a month. He soon returned to Paris. Taro remained in Spain to continue working. It was then she made some of her most powerful photos in a hospital and morgue after the brutal bombing of Valencia. Those photos in harsh, deep-contrast black and white are as strong as anything any photojournalist would produce in future wars. These include World War II, what we saw in Vietnam and what we are now seeing in Iraq. Many of her shots have the look of portraits, but instead of having been posed calmly in a studio, these happened on the run, caught in the moment, the way of the best in photojournalism. Gerda Taro has the sad distinction of being the first woman photographer to be killed in action. In July 1937 while covering a retreat, Taro hopped on the running board of a car carrying casualties. A tank smashed into the car and badly injured her. She died the next day. She was only 26 years old. Many thousands turned out for her funeral in Paris, where people proclaimed her an anti-fascist martyr. Until this exhibition, though known, we have not been able to see Gerda Taro's work in full. For the first time we can now gain a greater understanding of the person she was. It is too bad she never lived to become the person and the photojournalist she could have been had destiny taken a different turn. These photos by Robert Capa and Gerda Taro, especially from the Spanish Civil War, establish without question that every war in any age is the same. Its face, no matter the war, will never change. In these neatly, clearly mounted exhibitions at the International Center for Photography we see the faces of men under stress. We witness men with their weapons in fields, by ruined buildings and near broken walls. We watch men in machine gun nests looking to kill their enemy. Everywhere there are dead and wounded in the countryside and in hospitals and morgues. This powerful and enlightening exhibition is one that no one who cares about photography, history and the work of two great photojournalists – one immortal and the other rediscovered – should miss.

View The "Capa and Taro: Together at Last"

© Ron Steinman

|

|

Back to October 2007 Contents

|

|