|

Tokyo Calling

October 2007

|

|

|

"The telephone number you have dialed is inoperative." I dial again and double-check – the same response. I look in the e-mail for a mobile telephone number and there isn't one. My agency just e-mailed me a magazine assignment to shoot a reportage on mobile telephone usage in Japan and I'm trying to contact the journalist by phone – it's proving hard, not the best of starts.

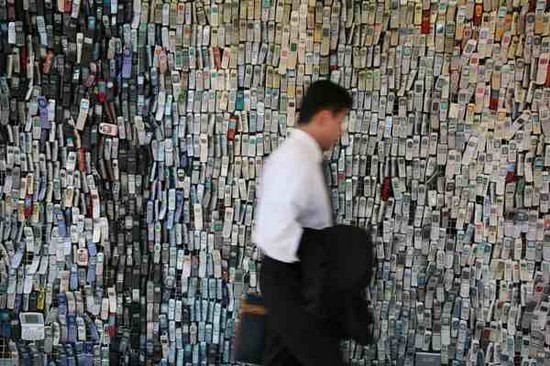

A man walks past the mobile telephone shop owned by Masanao Watanabe, in Edogawa-Ku, Tokyo, Japan, August 2007. Watanabe-san has more than 6,000 mobile phones which he has been collecting since 1994, some of which he has used to decorate the exterior walls of his shop in a bid to attract customers.

This is Japan and it's hard to escape from mobile telephones; they exist like appendages on people's arms. Sit down on a Tokyo train and you can be sure that half (if not more) of the people around you will be playing with their phones, using one of the many applications they provide. In a country of 127 million people there were, as of March this year, 117 million contracts for mobile phones. A high figure, and the numbers are reported to be steadily increasing. No wonder the line quality often sounds bad.

So a few days of not speaking with the journalist on the phone and a few e-mails later we meet. We go out into the streets to fulfill our by-now slightly toned down brief. A translator accompanies us and between her and me we feel we know enough people and places to get what we need – we hope.

Commuters use their mobile telephones enabled with prepaid financial credit to pass though the ticket gates of the Shinjuku JR East train station, in Tokyo, Japan, on Thursday, Aug. 23, 2007. The use of mobile phones as "i-wallets" is on the rise now that more and more of the required technology is being installed by transportation companies, shops, supermarkets, cafes and in vending machines.

Back into the city the team spends time in Shinjuku train station, which sees over a million commuters a day pass through it. We loiter by the ticket barriers shooting people using their IC-Card-enabled phones to swipe across a pad on the ticket barrier, paying by financial credit prepaid onto their phone for their train ticket access. I'm surprised at how many people already use this function, a function that is growing in popularity as more ticket barrier machines, vending machines and cash registers in shops have the technology installed.

Outside the station we find a businessman with two cell phones: one personal, one for work. His work phone has fingerprint recognition technology allowing him to lock and protect the information within. Incredibly in this country where people are often media-shy, he is happy to be photographed and interviewed.

Aya Matsuzaka, 29, conducts a mobile phone video call with her sister Maki Furuno, 25, and her niece Hina, 3, in Kobe city, from the Harajuku district of Tokyo, Japan, Aug. 23, 2007. Matsuzaka-san, who has recently married and moved to Tokyo, uses her phone's video call application to keep in touch with her family in Kobe and she does not find the cost prohibitive.

The following day we visit the flagship store of the Softbank mobile phone company: a gleaming white and bathed-in-light place. It's in the trendy area of Harajuku where kids wear fashions that make you think they'd dressed hurriedly in the dark, instead of actually spending hours preening themselves in front of mirrors. The Softbank store sells mobile phones in every shape, size, color and pattern, this application, that application, some with 5.1 MegaPixel phone cameras and price plans to suit every pocket. My head was swimming with all the varieties, the numerous lifestyle options for the ever-reachable-Tokyoite-on-the-Go, and I found myself saddened that we need so many choices in life.

Kenichiro Yamamori (a banker) and his 16-year-old daughter Julia, standing in front of a numerical digital display wall in the upmarket district of Roppongi, in Tokyo, Japan, Friday, Aug. 24, 2007. Yamamori-san uses his mobile phone for calling, sending e-mails, taking photos, shooting video, checking the Internet and watching television. His daughter has a mobile phone equipped with GPS (Global Positioning System) so that her father can find out her location should he wish to check. Julia also uses her mobile phone as an MP3 player for audio music.

On our last day we're in Shibuya, neon and video screens all around us blaring out the product of the day, thousands of pedestrians pushing along the sidewalks and we spot two young boys walking alone, colorful children's phones around their necks. We speak with them; they're 9 and 10. We go with them to meet their parents a few minutes away to check if it's OK to photograph and interview the boys. The parents are unconcerned about their kids being in the center of Tokyo on a Friday night by themselves – the parents can locate their sons with the GPS within the phones or the boys could activate the phone's 'rip-cord alarm' should they feel threatened.

My brief called for photos of people in "futuristic streets." Pictures in 1970s-looking streets would be easier in Tokyo but on our last evening we head for Roppongi where I know of a huge numerical digital display wall. It's as futuristic as I can think of and there we meet Kenichiro Yamamori, a banker, and his daughter. He tells us of using his phone for the Internet, e-mailing, shooting videos and photos, watching television, listening to radio and in particular, he explains that he uses GPS (Global Positioning System) to find his whereabouts or to guide friends to his locale. More interestingly, like the two boys' parents, he uses it to find out the whereabouts of his daughter Julia via her mobile when she is out at nights with friends. Sixteen-year-old Julia quietly tells us of updating her 'mixi (social networking site) blog' and of writing novels, all via her phone. Her dad listens with astonishment, not knowing she had a blog and novels. "We'll talk about this later," he responded, half jokingly.

My assignment was nearly complete; after four days of shooting I felt I better understood the use of phones in the nonstop, long-commute lifestyles of Tokyoites. I played with my own mobile on the way home, looking to see if it had an "assignment images download, edit and then send invoice" function. But it doesn't – that was still up to me. It was time to call my agents and tell them what I'd shot.

© Jeremy Sutton-Hibbert

|

|

Back to October 2007 Contents

|

|