|

→ December 2007 Contents → Column

|

Nuts & Bolts

December 2007

|

|

|

Bill Foley, freelancer, Pulitzer Prize winner, university teacher, bike nut and old friend, sent me an e-mail the other day.

"... at the college where I am currently imparting vast sums of wisdom … they want to look at resurrecting the darkroom which students walked away from 3 years ago and never looked back. It's actually cool, looks like a neutron bomb took out all the students and left all the enlargers, trays, etc. in place."

Let's hope they succeed. Film and the darkroom are more suitable to teaching some of the very basic photographic controls that can up your quality and separate you from the pack in this competitive profession. While many of us old dudes shoot very little film these days, much of the craft we learned and now apply to our digital work came from shooting film cameras without automation and producing negatives and prints in darkrooms with little tolerance for our errors.

Our mistakes (light pictures, dark pictures, flat pictures, contrasty pictures, pictures with motion blur, grainy pictures) weren't the pictures you would get with a camera on P and Photoshop tools set on Auto. But sometimes they were interesting. We started out stupider than our machines and ended up smarter. Some of us liked our dark mistakes; some of us liked our contrasty mistakes. After awhile, we stopped calling them mistakes and called them personal style and vision. (That remark, of course, was the only real mistake, branding us as pompous asses.)

But, later, as cameras evolved and automatically took care of things like exposure, and as Photoshop replaced the darkroom and automatically took care of things like contrast and brightness, we realized we didn't always agree with our tools. Canon, Leica, Nikon, Adobe, etc., might have a different sense of the qualities of a successful picture than we did. To put it in its cruelest terms, the machines might be playing a statistical con game where the goal was to produce a high yield of acceptable images at the sacrifice of different and exciting images. But how would you know if you had never seen anything outside of automatic and acceptable?

If it hadn't been for the memories of our personal style and vision (excuse me, analog errors) there's a good chance we would have accepted the statistical high yield of acceptable images produced by our digital auto tools and held to the belief that auto exposure can't be wrong, auto levels can't be wrong and that you will be smited down if you disagree with something so powerful and expensive as a digital camera or a computer program. We wouldn't have noticed the manufacturers also put other control settings on their cameras and computer programs.

If not doing this seems unreasonable, remember that a few columns back I mentioned that I had actually met two working professionals who had never gone off the program mode of their DSLRs. I suspect they don't adjust their "film" speed either. In my world, using a TTL meter like that means a lot of blown out highlights and, on occasion, just to make life interesting, some empty shadows.

I suppose part of the problem comes from the tendency to accept the manufacturers' suggestions as absolute gospel.

I suppose one of the benefits of film and a darkroom is that if you refuse to adjust the gospel (like the manufacturer's film speed or development time) to your personal standards you may get obviously bad results. I always halved my film speed when using a negative film and my handheld incident meter. TTL camera meters took a variety of adjustments. As a news shooter, I always favored shutter speed over f/stop and shot at 1/500 at f/2.8 when a lot of folks were at 1/125 at f/5.6. So adjusting the TTL meter suggested exposure and selecting a shutter speed and aperture appropriate to the subject was second nature by the time I started using digital. As to the final prints (prints, not reproduction in newspapers or magazines) silver, inkjet from scans or inkjet, from digital camera files. They all look alike, a little darker, a little more highlight detail and a little less shadow detail than you would get on autopilot.

Unfortunately, one problem faced by anyone who wants to use film as a teaching tool is the lack of cheap, no-frills cameras. In 35mm, I only know of one: the Vivitar V3800N with a 50mm, f/1.7 lens costs about $150. Outside of that (and please correct me if you know of another "student" camera) we start getting into expense and automatic features. And that means students might start using AUTOMATIC when the teacher isn't looking.

For years the scholastic starter setup was an inexpensive 4x5 view and sheet film; using it, you had no choice but to deal with each step of the photographic process and come to terms with how each step would affect the picture. Perhaps a school should invest in a brace of economical view cameras for the freshman class. They make you slow down, evaluate everything you are doing and teach you how, when you graduate, to use an 8x10 view, one of the few affordable film cameras that can still whip digital's butt.

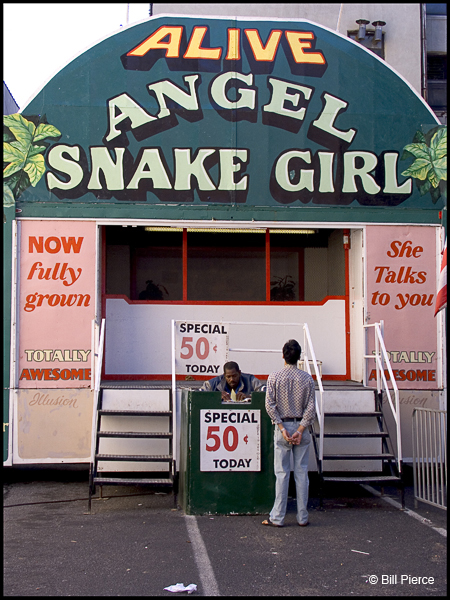

As to this month's "Picture which has nothing to do with the column," I like it because it's a picture of a real, rather than symbolic, freak show in New York City. And, yes, it is a digital picture.

© Bill Pierce

Contributing Writer

|

|

Back to December 2007 Contents

|

|