We were all standing on the highway when the tanks appeared, cresting the hill in the distance and rumbling right for us.

"The Russians!" everyone yelled at once, in dozens of languages. Maybe a hundred journalists from around the world were gathered on this main road, just outside of the besieged Georgian city of Gori, and we all knew that journalists had been brazenly robbed and even killed in this war by Russian forces or their associated militia elements. So everyone scrambled for their cars, piling inside and shouting at drivers to flee. Then hapless Georgian refugees carrying ad hoc cloth bags emerged from the trees alongside the road and started running away in terror from the approaching Russians, causing photographers who had packed into their cars to awkwardly scramble out again to take pictures. In moments the tanks (actually armored troop vehicles) were upon us.

© Chris Hondros / 2008 Getty Images

Russian armored vehicles on the move on Georgia's main highway.

I found myself in the chaos next to a European journalist I didn't know, both of us frozen on the side of the road as the first vehicles arrived in our midst. But nothing happened; the Russians simply continued on ignoring journalists and refugees alike as they motored in the direction of Tbilisi, about 40 miles away. Some of the soldiers piled on top of the troop transports even smiled and waved.

"The Russians are waving," my new friend said, staring straight at the convoy.

"Yes, they are waving," I replied tonelessly. It occurred to me that I probably should be photographing something. We watched as dozens more vehicles rumbled past. Finally he shrugged.

"Let's follow them," he said.

"Good idea," I answered.

So we did, the international press corps piling into our rented cars, many driven by terrified Georgians hired by the day from the Marriott Marquis in Tbilisi, and more accustomed to ferrying foreign businessmen around the capital than they were to chasing Russian armored vehicles in the middle of a war. (More than one driver panicked and skidded off without their fares back to Tbilisi at the first sign of the Russians, leaving their stranded journalists on the side of the road looking for rides.)

© Chris Hondros / 2008 Getty Images

Georgian women crush against a bus where food aid was handed out in the besieged town of Gori, Republic of Georgia.

We weren't sure what might be happening: was this the invasion of Tbilisi happening before our eyes? The armored column continued its march down the highway for many miles. Photographers leaned out of windows and stood in sunroofs shooting pictures alongside as the armor rolled. But then, about halfway to the capital, the troops turned left off of the highway onto a side road, disappearing into the hills in the distance. The Russians were deep into the Republic of Georgia but there would be no invasion of Tbilisi this day.

**

The start of a war is a little like the early stages of a romantic relationship: always intense and inclined to make people too likely to believe the things they hear even when they have the experience to know better. So when the Russians reported on the first day of the war that 2,400 of their allied Ossetian comrades had already been killed by Georgian forces, it couldn't help but gather the world's attention and I scrambled to get from New York to the conflict as fast as I could.

But that number, so confidently offered up by the Kremlin, of course in the end turned out to be wildly inflated. Numbers are still not precisely certain but in fact it seems that less than 200 Russians and Ossetians were killed in the course of the whole war—a grim tally but hardly the "genocide" alleged by Moscow, a word that's quickly becoming meaningless through overuse in the parlance of international relations.

The Georgians joined the misinformation fray. "CITY OF GORI RAZED TO THE GROUND," boomed one headline of an English-language newspaper in Tbilisi which, as I saw for myself, was hardly the case. (Georgians ought to know better: Chechnya borders it to the north, and they need to look only as far as Grozny to see what a truly razed city looks like.)

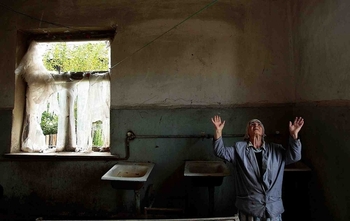

© Chris Hondros / 2008 Getty Images

A Georgian woman prays as she stands in the deserted kitchen of an apartment complex that was bombed by Russian forces in Gori.

But even if it wasn't leveled, Gori did suffer heavily in the war and it's where I spent most of my time for the two weeks I covered the conflict. Most of the city's 150,000 residents fled as Russian forces stormed and occupied it, leaving an eerie ghost town of broad boulevards and broken windows, wandered forlornly by the occasional old man or woman too poor or stubborn to leave. And several apartment complexes, at least, were indeed demolished by Russian air bombardments; at least dozens died in these attacks and maybe hundreds.

One communist-era apartment complex on the main road out of town was especially savaged and it became the backdrop for many journalists' reports on the war. I headed there myself, traveling with fellow photographers Ron Haviv, Michael Robinson-Chavez and Jared Moossy. (Having had enough of mutinous drivers we ended up renting an Avis car in Tbilisi and driving ourselves for most of the trip.)

© Chris Hondros / 2008 Getty Images

A Georgian man carries a donated cot up to his family in a room of an old ministry building in Tbilisi.

The buildings were scarred by fire and torn by explosions, the all-too-familiar scene of tangled steel rebar and fire-blacked concrete. There are places in the world where it's more shocking to see a live person than a dead one and so it was here, when amidst the rubble and doom, the face of an old woman appeared in a first-floor window, staring blankly outside. We made our way inside, carefully picking our way through the rubble.

The woman was distraught and terrified, but seemed intent on staying in what was left of her apartment in the destroyed building. She had some water in plastic bottles but hadn't eaten in days, so Jared Moossy ran out to the car and grabbed the plastic bag of pastries and sandwiches he had pilfered from the Marriott's breakfast buffet that morning and we left it with her. When we ventured back to check up on her the next day and bring her more supplies, she was gone.

**

But most Georgians didn't stay at all, fleeing Gori and the Georgian villages in South Ossetia in the first days of fighting. These thousands of people ended up mostly in Tbilisi where the government struggled to find shelter for them. Many ended up in dilapidated Communist-era ministry buildings that were hastily turned into makeshift refugee camps; we visited one near downtown Tbilisi.

Hundreds of refugees were gathered in the once-ornate lobby waiting for a handful of beleaguered officials to pass out green cots that were part of the U.S. government donation of aid that had arrived the previous day. Once a refugee got his or her cot, they made their way upstairs to claim a room in the sprawling complex, one room per extended family.

The refugees from Gori, I knew, would go home eventually; Russian forces already seemed to have no desire to permanently seize the city, lying as it does on unchallenged Georgian territory. But just a few kilometers north of Gori lies the provincial border of South Ossetia beyond which the lands have long been in dispute. Thousands of Georgians lived in South Ossetia province up until Aug. 7, the beginning of the war, but almost all of them now have fled, and some of those were sitting on crates in front of me in the spare rooms of this refugee camp. These Georgians from north of Gori seemed to sense that the world they had known had come to an end: the territory around their villages was being permanently fortified by Russian forces even as we spoke there. Those people will probably never go home.

**

© Chris Hondros / 2008 Getty Images

Georgian refugees looking for shelter stand and wait to be placed in a camp at a resettlement office in Tbilisi.

All in all it seems to me that the world is underestimating the sea-change that occurred in international politics as a result of the Russian-Georgian war of 2008. Russian forces seized territory and projected power on foreign soil in ways they haven't since the end of the Cold War. The international community looked impotent and naïve in the face of the crisis, with President Sarkozy of France huffing about Georgia's territorial integrity (which, as far as South Ossetia is concerned, is long gone) and George W. Bush solemnly announcing that Russia's actions were "unacceptable in the 21st century" -- as if something magical had happened at the stroke of the year 2000 that disinclined countries from their age-old hunger for resources and territory. We might no longer expect war between, say, France and Germany, but most of the rest of the world lives in more dangerous neighborhoods and I see nothing in the geopolitical tea leaves that leads me to think that this will be the last invasion and war we see in the coming years. In fact, with the thirst for energy and resources reaching a fever pitch, the pace of invasions and occupations could very well pick up, all over the world. It might well be the start of unquiet times.

Chris Hondros was born in 1970 in New York to immigrant Greek and German parents, both survivors of World War II, and moved to North Carolina as a child. After taking a Masters degree from the School of Visual Communications at Ohio, Hondros returned to New York in 1998 to concentrate on international reporting. He's covered most of the world's major conflicts since the late 1990s, including wars in Kosovo, Angola, Sierra Leone, Lebanon, Afghanistan, Kashmir, the West Bank, Iraq, and Liberia. He is a senior staff photographer for Getty Images, and his work frequently is published in the leading newspapers and magazines of the U.S., Europe, and Asia. Hondros has received dozens of awards, including multiple honors from World Press Photo in Amsterdam, the Pictures of the Year Competition, and the John Faber Award from the Overseas Press Club

In 2004 Hondros was a Nominated Finalist for the Pulitzer Prize in Spot News Photography for his work in Liberia, and in 2006 he won the Robert Capa Gold Medal, war photography's highest honor, for his work in Iraq.

In addition to his photography, Hondros is a frequent essayist on issues of war.

See hundreds more of Chris Hondros' images at: http://www.gettyimages.com/Editorial/News.aspx.

Click on the links below to read some of his previous Digital Journalist dispatches:

• http://www.digitaljournalist.org/issue0712/going-to-court-in-iraq.html

• http://www.digitaljournalist.org/issue0701/grave-and-deteriorating.html

• http://www.digitaljournalist.org/issue0511/dis_hondros.html

• http://www.digitaljournalist.org/issue0401/dis_hondros.html

• http://www.digitaljournalist.org/issue0308/ch_intro.html