So please please please

Let me, let me, let me

Let me get what I want

This time.

So please please please

Let me, let me, let me

Let me get what I want

This time.

Credit Morrissey of The Smiths with the lyrics and Leica for finally making it come true for Leica M rangefinder photographers everywhere. Leica has finally delivered (albeit in very small quantities so far) the camera many were hoping for three years ago when Leica delivered its first digital rangefinder.

The Leica M9 is the world's smallest 35mm-equivalent full-frame camera. Introduced on (hint, hint) September 9, 2009 (i.e., 09/09/2009) at (close to the announced time of) 9:09 a.m. via a worldwide Webcast from New York City. It was a huge moment for Leica as they announced two more completely new camera systems at the same time – the quasi-consumer X1 point-and-shoot (quasi because is there really a market for a consumer point-and-shoot that carries a $1,995 price tag?) and the professional S2 system. The S2 system, Leica's alternative to medium-format digital cameras from the likes of Hasselblad, Mamiya, and Phase One, had been talked about for months but this was its formal announcement.

Support our sponsors

The M9 was something of a surprise. Its predecessor, the M8.2, itself an update to the M8 originally introduced in 2006, was just released earlier this year. Less then eight months later, the M8.2 was obsolete and discontinued (along with the M8).

Many considered the M8/M8.2 to have been an extended beta release anyway. The original M8 was plagued with numerous problems that were patched along the way and were successfully (but only partially) resolved with the introduction of the M8.2.

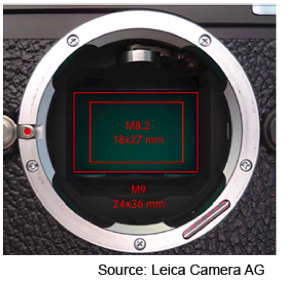

Many, myself included, thought the M8.2 would be our best digital rangefinder option for quite some time. You see, we were first told by Leica that a digital version of the venerable M rangefinder film camera was impossible (the Japanese proved that this was not the case with the release of the first digital rangefinder camera, the Epson R-D1, in 2004). Then we were told that the very narrow design of the Leica M cameras (which requires lenses with a very short flange focal distance) was an insurmountable technical challenge to accommodate a full-frame, 24x36mm sensor. Basically, the lens sits too close to the surface of the sensor for adequate edge-to-edge, corner-to-corner coverage without serious vignetting taking place.

The M9 incorporates an 18.5 megapixel 23.9x35.8mm CCD image sensor manufactured by Kodak – the fourth Leica camera to use a Kodak sensor.

Perhaps there was a technological breakthrough in Rochester, N.Y,. that helped to bring the M9 to life so soon on the heels of the M8.2. Once the 09/09/09 rumors began this past summer, there was little doubt what Leica had in store – prior to that few expected to see a full-frame digital M camera until sometime in 2010, especially since the M8.2 was so fresh.

Let Me Get What I Want

With its full-frame sensor, the M9 user once again has virtually the entire armada of Leica M-mount lenses (some dating back to the 1950s) available at their intended focal length – no more 1.3x crop factor to consider. The familiar field of view and depth-of-field characteristics of a given lens that a film camera user came to know was back. There is no more "effective focal length" mumbo jumbo where a 35mm lens, for example, was cropped down to something close to a "50mm lens" which then had more depth of field than a legit 50mm would have.

With its full-frame sensor, the M9 user once again has virtually the entire armada of Leica M-mount lenses (some dating back to the 1950s) available at their intended focal length – no more 1.3x crop factor to consider. The familiar field of view and depth-of-field characteristics of a given lens that a film camera user came to know was back. There is no more "effective focal length" mumbo jumbo where a 35mm lens, for example, was cropped down to something close to a "50mm lens" which then had more depth of field than a legit 50mm would have.

This behavior alone kept many Leica film camera users from considering the M8 and M8.2. In fact, with the improvements that came with the M8.2 (which were significant), the crop factor issue was arguably the single largest barrier to adoption of the digital M for those Leica users willing to embrace digital imaging.

Then there are those who will have to have their M6, M7, or MP film cameras pried from their cold, dead hands but that is another story.

So, I think it is safe to say that the M9 is the digital M camera that most everyone wanted from the beginning. We got the "beta" M8 for two and half years and the "beta 2" M8.2 for approximately eight months while Leica and Kodak engineers worked to solve what was originally called a technical impossibility. Now (or as soon as Leica can ramp up production), the "perfect" digital M camera will be available – to those who can afford it.

It is certainly what I have wanted for the past five years or so.

Why an M9?

Before getting into commentary about the new Leica, I want to go back to something I wrote about in the second paragraph.

Before getting into commentary about the new Leica, I want to go back to something I wrote about in the second paragraph.

What makes the M9 an important development beyond providing long-term Leica stalwarts with a dream come true, is its size. It is no small feat of engineering to bring forth a full 35mm-frame digital camera in such a compact camera. I was struck by this image in a Leica training document comparing the M9 footprint to those of DSLRs.

This sums up the size issue very clearly. Certainly there are times when the speed and telephoto lens capabilities of a DSLR are necessary. But for photographers who carry their camera everywhere, every day, and who demand the highest image quality, the choices are limited. When purchase price is set aside (the M9 carries a list price of $6,995 as of this writing), the diagram above makes a pretty compelling case for the M9.

One more thing.

Look at the images to the right. That's the M9 on top, the Canon 5D Mark II, and finally the Nikon D700. The 5D and D700 correspond to the white frame outline surrounding the M in the relative size comparison image above.

Look at the images to the right. That's the M9 on top, the Canon 5D Mark II, and finally the Nikon D700. The 5D and D700 correspond to the white frame outline surrounding the M in the relative size comparison image above.

Okay, say you are a cave man. Which of these cameras do you think you could operate? The bottom two, especially the D700, look more like computer terminals than cameras.

The larger gray silhouettes in the size comparison image above represent the Canon 1D and Nikon D3 (or similar models) which have even more controls, buttons, and levers.

Again, as I have said, all these cameras have their well-deserved places in the overall scheme of things but the more analog control approach taken by Leica with the M8/M9 (and with the forthcoming X1) is a distinctly different approach to digital cameras than that taken by the Asian camera manufacturers. And one that I think strongly appeals to many photographers who remember what a camera felt and looked like before the digital revolution. Dare I say, what a camera should look and feel like.

What's New in the M9

Not every reader of this review will be upgrading from an M8 or M8.2 but I don't think that any review of the new M9 would be complete without describing how they differ. The most significant differences are listed below (in no particular order).

- The M9 has a full-frame sensor equivalent in size to a 35mm film frame (the M8/M8.2 has a 1.3x crop factor).

- The M9 is an 18 megapixel camera (the M8/M8.2 is 10 megapixels).

- The M9 supports uncompressed (14-bit) DNG image storage and with the provided copy of Adobe Lightroom, a 16-bit workflow (the M8/M8.2 supported only 8-bit DNG files).

- The M9 has an integral UV/IR cut filter covering the sensor (the M8/M8.2 required UV/IR cut filters to be attached to each lens).

- The M9 returns to the traditional focal length frame line pairings of its film cameras (28/90, 50/75, and 35/135). (The M8/M8.2 required different groupings to accommodate the crop factor and omitted the 135mm frame lines altogether).

- The M9 permits the manual selection of the lens type attached to the camera (the M8/M8.2 required a special 6-bit code to be engraved on the lens mount); the M9 still recognizes the lens coding if it is present.

- The useless Snapshot mode of the M8/M8.2 has been replaced with a new Snapshot Profile which simplifies the camera's menu presets.

- The selection of the Snapshot profile is now a menu selection (the M8/M8.2 had an "S" setting on the shutter speed dial); the "S" position on the M9 dial has been replaced by an additional slow shutter speed of "8"s.

- As what most likely was a cost-cutting move, the M9 loses the scratch-resistant Sapphire Glass Cover over the LCD that was introduced with the M8.2 – no great loss there.

- The M9 weighs 40g (0.8 oz) more than the M8.2.

- The M9 adds an Exposure Bracketing feature of three, five, or seven frames in (+/-) 0.5 EV increments (the M8/M8.2 had no such capability).

- The M9 histogram display adds indication for underexposure (the M8/M8.2 had only overexposure indication).

Addressing a concern still left around after the introduction of the improved M8.2, the M9 permits the self-timer mode to be disabled. A frequent complaint of the early models was that the rotating control around the shutter release button could be accidentally slipped into self-timer mode which effectively disabled the camera unexpectedly (the M8/M8.2 did not have this option).

Addressing a concern still left around after the introduction of the improved M8.2, the M9 permits the self-timer mode to be disabled. A frequent complaint of the early models was that the rotating control around the shutter release button could be accidentally slipped into self-timer mode which effectively disabled the camera unexpectedly (the M8/M8.2 did not have this option).

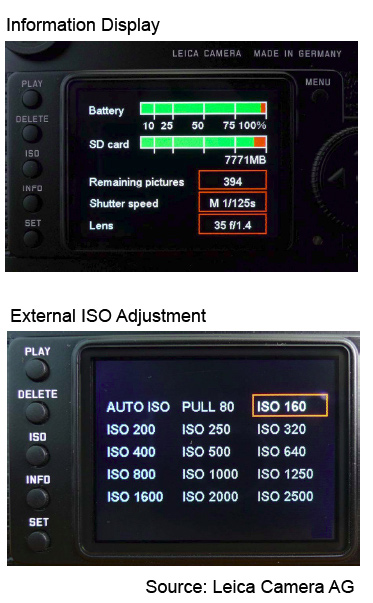

- The M9 loses the top plate battery and exposure counter window of the M8/M8.2. This information is now incorporated into the New Information Display on the rear LCD screen. This new screen also displays the shutter speed currently set and which lens is on the camera.

- The M9 replaces the rather useless Protect button of the M8/M8.2 with a new ISO button that activates what Leica calls External ISO Adjustment. This makes it easier and quicker to set the camera's ISO sensitivity. The M9 also includes many more ISO levels as you can see in the figure (the M8/M8.2 were limited to 160, 320, 640, 1250, and 2500).

- The M9 introduces the Soft Advance feature. When enabled via a menu selection, this permits the shutter to be released with a much softer touch of the shutter release button – this can be useful when using slow shutter speeds at the expense of AE (auto-exposure) lock when the shutter button is depressed halfway.

- The M9 introduces a direct method to adjust (+/-) exposure compensation for the next exposure without using the Set button and the menu system by depressing the shutter release button halfway and using the setting ring on the back of the camera.

- The M9 shutter blades differ from the M8/M8.2. The M8/M8.2 has a single center-most blade of light gray among otherwise black blades while the M9 has the same (or similar) center gray blade surrounded top and bottom with slightly darker gray blades. Since the camera's light metering system reads reflections off of the shutter blades to determine exposure, one would assume that this change improves center-weighted metering accuracy.

This is an impressive list. To be honest, until I did my research for this review, I did not realize how many improvements beyond just the larger sensor were done to the M9.

Don't get me wrong, the M9 still has some issues – one major – that reinforces the notion that the M9 is not ready for prime time as a pro's tool when compared to advanced Canon and Nikon DSLRs (more on this later). Still, the M9 is nevertheless a significant step forward to digital rangefinder photography and in a broader sense, digital camera design in general.

Using the M9

M9s are still in very short supply. Thanks to Jerry Sullivan at Precision Camera and Video in Austin, Texas, I was able to borrow a loaner from Leica for a couple of days in mid-September.

M9s are still in very short supply. Thanks to Jerry Sullivan at Precision Camera and Video in Austin, Texas, I was able to borrow a loaner from Leica for a couple of days in mid-September.

As a long-time M7 user and an M8.2 user since February, I was immediately right at home with the M9. Learning curve = 0. My favorite lens for my M7 is the Tri-Elmar that delivers a 28mm, 35mm, and 50mm lens in a single compact package. With its 1.3x crop factor, however, I never liked using this lens on the M8.2.

With the Tri-Elmar on the M9, it was like back to the future. With the LCD preview turned off, a photo session at Austin's Pecan Street Festival with the M9 and Tri-Elmar was all but indistinguishable from any that came before it with the same lens and an M7.

Strangely, a simple change in the design to the M9's top plate (compared to the M8 and M8.2) added to this experience. The left side of the top plate is notched to more closely match the appearance (if not the ergonomics) of its film predecessors. I like to think that this was someone's brilliant idea to more closely mimic the look and feel of an M7 – because that certainly is what it did for me. I doubt that this change has any functional purpose.

Strangely, a simple change in the design to the M9's top plate (compared to the M8 and M8.2) added to this experience. The left side of the top plate is notched to more closely match the appearance (if not the ergonomics) of its film predecessors. I like to think that this was someone's brilliant idea to more closely mimic the look and feel of an M7 – because that certainly is what it did for me. I doubt that this change has any functional purpose.

To me, the M9 represents total success for Leica in bringing the "M camera experience" into the digital age.

Users of non-automatic-exposure Leicas like the M6 and MP (and, okay, M5), can enjoy the digital M experience by turning the shutter speed dial off "A" and manually setting their shutter speeds just like the old days. Taking this to the logical, if not silly extreme, even completely manual M2, M3, and M4 users can join the fun by simply ignoring the exposure meter indicator at the bottom of the viewfinder.

Regrettably, I had to return the camera sooner than I wanted to. However, with its significant similarity to the M8.2 and after capturing some test images, I am prepared to offer a pixel-peeking review of the M9's image quality compared to several other cameras, plus a few other facts, figures, and opinions.

The Major Flaw of the M9

For all there is to recommend the M9, there are a few things where cameras selling for thousands of dollars less put it to shame and may affect the suitability of the M9 for certain pro applications.

These include the following:.

- Capable of only 1-2 frames per second

- Lack of weather sealing

- No live view

- No integrated dust removal system

- Absence of any video mode

Whether these are deal killers for you depends on what type of photography you do and how willing you are to overlook certain things so you can continue to justify paying $7,000 for a camera that maybe should know better.

Of these, however, only one amounts to much as far as I am concerned – and becomes the only major (though hardly fatal) flaw of the M9.

I think it is safe to say that few Leica M photographers care that the M9 cannot fire off pictures at five frames per second (or at whatever rate that some of the better DSLRs are capable of). This just doesn't fit into the modus operandi of a rangefinder photographer.

But shouldn't the camera be able to process and save images as fast as the camera is able to take them?

The M9 is generously rated at two frames per second. Okay, but after seven or eight exposures, the camera clogs up and forgets about taking more for what can seem like an eternity if you're missing the action – just watch the blinkity-blinkity of the red LED for awhile. During this time you can rationalize why it's okay to miss the pictures you can't take right now because the M9 is "so cool" and/or explain to your subject that they can take a break while the camera "is thinking."

This is not a matter of a larger frame buffer in the camera. A larger buffer would also eventually fill up and you'd have to wait even longer.

This is a matter of an under-powered image processor – basically, the M9's "brain" is way too slow.

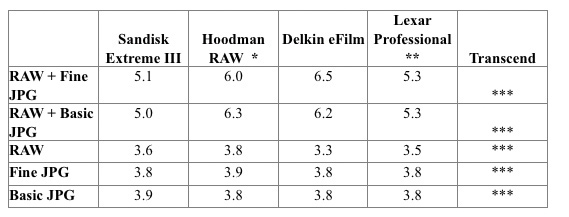

And it's not a matter of slow SD cards. I have tested the M9 (and M8.2) with a variety of cards (results below) and there is little difference (or improvement) from one card to another.

For all that Leica got right when they went from the M8/M8.2 (which had that same problem) to the M9, this is their single biggest failure. If there is a reason NOT to buy an M9, this is it.

I shoot compressed RAW + fine JPG and it happened very frequently during my test of the M9 just as it does with my M8.2.

Inexcusable.

When I press the shutter button, I expect the camera to take a picture. Every time.

Why Leica failed to upgrade the M9's processor to one that could keep up with the camera's meager two frames a second boggles the mind. More than anything else this is the camera's most serious flaw.

Will I live with it?

Yes.

SD Card Test Results

In hopes of discovering a way around the "slow brain" problem described in the previous section, I acquired five major brand 4GB SDHC cards and tested them. I timed how long it took between the time the shutter was pressed and when the flashing red LED went out, indicating that the camera had finished processing the captured image and saved it to the card.

Timings were not obtained using rigorous scientific methods but are representative of real-world experience with the camera.

With the exception of the Lexar (see note below) all cards were formatted in the camera before the tests. The times are averages of three or four exposure/write cycles.

* The camera won't power on with 8GB version of the Hoodman RAW card installed.

** The camera fails to format the Lexar Professional card.

*** The camera fails to recognize the Transcend card

As you can see the measurements are not drastically different from card to card. It is interesting to note the various failures. My experience has led me to choose the Sandisk card for my personal use.

The sad truth revealed by this test is that the M9's "major flaw" described in the previous section is not related to the brand of SD card used in the camera. In fact, it appears that if the card works at all, the performance of the camera will not be significantly different.

The High ISO Trade-Off

As mentioned above, the M9 tops out at ISO 2500.

Actually, this is not a huge deal for me. With the high-end DSLRs (like the Nikon D700 and Canon 5D Mark II) you get pretty amazing performance up to ISO 6400 but usually you are stuck with heavy and slow zooms that open up to f/2.8 if you are lucky – f/4 to f/5.6 are typical. Okay, there are fast primes too for these DSLRs but it is a rarified breed that actually uses them.

In the Leica M world f/1.4 prime lenses are available in focal lengths from 21mm to 75mm, albeit at a princely price of course. F/2 and f/2.8 lenses through this same range are much more commonplace and many are well within the reach of the average Joe price-wise. More rarified f/0.95, f/1, f/1.1, and f/1.2 35mm and 50mm lenses are also available in the Leica M mount – a couple of these are priced in the $1,000 neighborhood.

The available lens pool for the M9 includes current and past models made by Leica, Cosina/Voigtlander, and Zeiss. Older lenses made by Minolta and Konica (before they merged) can still be found.

So, the argument goes that the DSLRs offer amazingly clean high-ISO performance so slow zoom lenses can be used in more lighting situations. The same can be said for the image stabilization phenomena.

Leica doesn't have to bother with this fancy and expensive image processing technology and image stabilization because there are so many fast lenses available – and hand-holding a Leica M camera as slow as 1/8th of a second is possible for many.

I swear I can hear people whispering something about relationalization at this point.

Would an image-stabilized M9 with the high-ISO performance of a Nikon D700 be a good thing? Well, of course. So would a 12 megapixel APS quality image from my iPhone camera but I'm not holding my breath for that either.

Is the M9 topping out at ISO 2500 acceptable?

Yes, but … well, maybe.

High ISO Performance

I've lost count of the number of M9 reviews I've heard about bouncing around the Internet. I've made a point not to read any of them once I was scheduled to write what you are reading right now.

I'm sure that many of them are more techie than this one.

I already know that Leica lenses (Voigtlander and Zeiss too) are some of the best available for any camera. I know that the M9 (like the M8/M8.2) has no anti-aliasing filter over the sensor.

For those reasons, there is no question that pictures captured by the M9 are going to be sharp. It astonishes me sometimes how sharp some of my M8.2 images are straight out of the camera – there are times that capture and/or output sharpening actually degrades the image. My limited experience with the M9 produced the same results.

So, I don't need to see any sharpness comparisons of the M9 against other cameras.

What does interest me is how M9 images look at high ISOs. And not just in color. How many times have you heard that in black-&-white "high ISO noise looks like film grain," implying that it is okay. Since I pretty much pretend that my M8.2 (and future M9) is loaded with digital Tri-X or Neopan 1600, this presumption is important to me.

I set out with a collection of different cameras to form my own conclusion about the M9's high-ISO performance – both subjectively and how it compares to other full-frame digital cameras on the market today.

I took a variety of test photographs with the M9, a M8.2, a Nikon D700, and a Canon 5D Mark II. To keep things simple for this review, I will be comparing just the lowest and highest comparable ISOs of each camera. The final comparison of the M9 at ISO 1250 and ISO 2500 does a pretty good job at filling in the blanks.

I'm not going to declare a winner. I'll let the tests speak for themselves. You decide what you find acceptable.

The image I settled on as the source of noise comparisons is below.

The first comparison shows four crops at the lowest comparable ISOs of the M8.2, M9, 5D Mark II, and D700.The comparisons that follow are of a crop of the light fixture right in the center. This is a fairly dramatic crop so noise (if visible) will be pronounced. All test images were derived from the camera's RAW file. Other than selecting "Auto White Balance" in Lightroom and some minor levels adjustments, the crop, and saving the result as a JPG, the test images are otherwise unprocessed.

The first comparison shows four crops at the lowest comparable ISOs of the M8.2, M9, 5D Mark II, and D700.The comparisons that follow are of a crop of the light fixture right in the center. This is a fairly dramatic crop so noise (if visible) will be pronounced. All test images were derived from the camera's RAW file. Other than selecting "Auto White Balance" in Lightroom and some minor levels adjustments, the crop, and saving the result as a JPG, the test images are otherwise unprocessed.

Noise-wise they all look very clean to my eye. The one interesting thing is the blown highlight in the lamp's dome in the M8.2 image. This may simply be a poor exposure on my part or it may reflect that the M8.2 has less dynamic range than the other three cameras. (The relative lack of sharpness of the Leica images is due to poor manual focusing combined with a slow shutter speed.)

The next comparison shows four crops at the highest comparable ISOs of the M8.2, M9, 5D Mark II, and D700.

The next comparison shows four crops at the highest comparable ISOs of the M8.2, M9, 5D Mark II, and D700.

Despite rumors to the contrary, the M9 noise at ISO 2500 looks pretty well managed. Reports that the M9 has improved noise characteristics over its M8/M8.2 predecessor are hard to confirm from this single image since to my eye they look pretty much the same. The blown highlights remain in the M8.2 image and are more evident in the M9 image compared to the ISO 160 image. Once again, this suggests lower dynamic range in the Leica cameras. It is safe to say that the M9 is not as clean as either the Canon or Nikon.

Okay, how about that "noise looks like grain in black-&-white mode" claim? You be the judge. The images were converted using the Adjustment -> Black and White control in Photoshop CS3.

Okay, how about that "noise looks like grain in black-&-white mode" claim? You be the judge. The images were converted using the Adjustment -> Black and White control in Photoshop CS3.

The M8.2 image looks more "grain-like" to my eye. Neither the M8.2 nor M9 images look terrible but neither contains what I'd describe as a nice grain pattern. Perhaps some sharpening would help. The Canon and Nikon images remain virtually "grain-less."

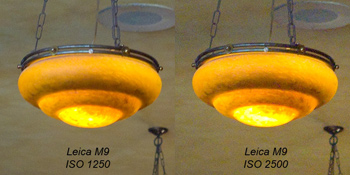

Finally, a comparison of the M9 at ISOs 1250 and 2500 is very interesting.

Finally, a comparison of the M9 at ISOs 1250 and 2500 is very interesting.

The M9 at ISO 1250 looks very clean – quite a dramatic difference from ISO 2500. Perhaps my statement ending the previous section should be revised.

Is the M9 topping out at ISO 2500 acceptable?

Kind of … but ISO 1250 is more than acceptable.

The M9 and Infrared

The biggest scandal of the M8 (which was introduced in the fall of 2006) was the camera's increased sensitivity to light in the infrared (IR) spectrum. The problem remained in the M8.2.

This flaw rendered the camera incapable of capturing true black (as our eyes perceive it) of certain surfaces, particularly synthetic fabrics of clothing and furniture. These reflect IR radiation and result in a magenta color cast in areas that should be rendered black. This color cast is extremely difficult to correct in post-processing.

The solution was to add a UR/IR cut filter on each lens. A solution, yes, but a hack no matter how you look at it.

Finally with the M9, Leica created a filter covering for the sensor that has resolved this issue without degrading image quality – presumably why this filter was absent in the M8/M8.2.

This meant that the M8/M8.2 was a pretty good camera for artistic IR photography. Some photographers serious about IR work send their cameras to custom shops to remove the IR filters installed by the manufacturer. Here, the M8/M8.2 came without one to begin with.

As an interesting exercise, I compared the IR sensitivity of the M9 against that of the M8.2. Placing an 89B filter on my Tri-Elmar, I photographed the same scene. The resulting photographs are below:

Clearly the M9 is four f/stops less sensitive to the same scene when only IR light is admitted to the sensor. Also, the Wood Effect (the rendering of green foliage as glowing white) is less pronounced in the M9 photograph.

Clearly the M9 is four f/stops less sensitive to the same scene when only IR light is admitted to the sensor. Also, the Wood Effect (the rendering of green foliage as glowing white) is less pronounced in the M9 photograph.

Doesn't have much practical application unless someone is interested in IR photography with one of the digital Leica M cameras – if that is the case, the M8 or M8.2 is your camera.

Conclusion

The M9 is a cumulation of a dream for many photographers.

Considering the nature of rangefinder photography and the history of the Leica M family, the M9 is as close to perfection as modern technology allows.

Individual wish lists abound and no camera can be all things to all people but the M9 is a hot commodity right now. Leica will sell a lot of them – to frustrated M8 and M8.2 owners; to film Leica camera users who could never accept anything less than a full-frame camera; to photographers new to the Leica camp who are looking for smaller, more discreet alternatives to their Nikon, Canon, and Sony full-frame behemoths.

Funny, the Leica community is a strange place. The M9, a surprise on the market in 2009, is still not quite good enough to some and the murmuring for a perfect digital Leica, the M10, has already begun.

Well, friends, the M9 is da bomb. Other than a fix for the "major flaw" described above, it is difficult to envision why an M10 is even going to be necessary.

I'm finally going to get what I want this time, this time.