Rewind: Wars and Memories

by Dirck Halstead

PART I(The Present)

Surin, Thailand, October 17, 1997

Tales of war, as seen through the eyes of photographers; this was one of the subjects I wanted to feature on this website.

In July of 1954, through an amazing series of events, I became the youngest war photographer in LIFE magazine's history. I found myself at the age of 17 in the middle of combat during the Guatemalan revolution.

In the mid 1960s, I opened the UPI picture bureau in Saigon.

Vietnam would continue to call me back...in 1972 and 1975 for TIME.

I photographed the first United States Marines landing on the beaches in DaNang, and the last Marines to leave from the roof of the embassy in Saigon in 1975.

There is an old saying in this business, once Indochina has got you, it will never let you go.

I had planned to start writing the first part of what will be a continuing series on my experiences on battle fronts, and of the good friends I met and lost.

At 3:00 a.m., Monday morning of the Columbus Day weekend, I was wakened by a phone call from Sam Roberts, the head of new media for the New York Times.

"Dirck, it's a go...we have an exclusive interview with Pol Pot in Cambodia. Can you be on a plane for Bangkok this morning, to meet up with Elizabeth Becker, ready to go into Cambodia tomorrow?"

I had a brief discussion with Roberts the preceding week. He was looking for a "Platypus Photographer," someone who could do both stills and video to accompany their foreign editor, Elizabeth Becker, on what he described as a trip to Vietnam. By the weekend, I had heard nothing further. It was not uppermost in my mind until that early morning call came.

Nothing was packed; no clothes, no camera gear. A quick check of plane schedules found a United flight leaving for Bangkok at 9 a.m.--check-in at Dulles was at seven.

Somehow I managed to pack some human essentials, get to the office and throw my gear into a case, and stumble onto the plane .

Twenty four hours later I was in Bangkok.

Elizabeth Becker, an energetic reporter who looks like a cross between Faye Dunaway and Cissie Spacek, had covered Cambodia since the early seventies for the WASHINGTON POST, NATIONAL PUBLIC RADIO, and now was eager to get back into the field from her desk job at the TIMES.

Elizabeth had been contacted by a friend from her old Cambodian days, Steve Header, who had received a call from a Khmer source he had known for almost twenty years.

Header had worked with Elizabeth in the early seventies, later with Amnesty International, and then with the United Nations in Cambodia, from 1992 till 1993. Header is generally considered the world's leading authority on the Khmer Rouge.

Fluent in the language, Header would be able to provide the necessary translation to Elizabeth's questions.

The only other sighting of Pol Pot in this decade was by a journalist working for the Far Eastern Economic Review, Nate Thayer, who had won world-wide attention with his exclusive articles, photographs and video earlier this year.

The hotel in Surin (six hours northeast of Bangkok) would be the base from which we would cross the border, into the mountains of Cambodia. During check-in we encountered a shocked Thayer. He had also been contacted by the Khmer Rouge and promised another exclusive interview.

Thayer, with his glistening bald dome, looked like a leaner version of Marlon Brando as Col. Kurtz in "Apocalypse Now." His remark to us, " it's nothing personal...I just have to do what I have to do," were a warning that we were getting into dangerous territory.

At daybreak the next morning, we awoke to find that Thayer and his TV crew had already left the hotel. The guides who were supposed to meet us were nowhere to be found.

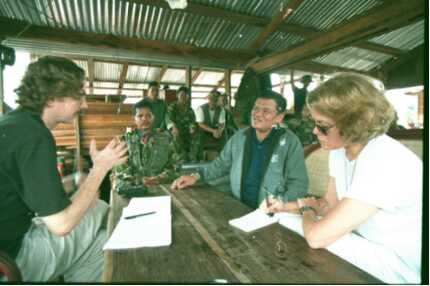

After a morning of frantic phone calls, we were finally led to a meeting across the Cambodian border with General Nhek Bun Chhay. He had been deputy chief of the Royal Cambodian Forces and had to flee for his life during a recent coup. His base camp had been attacked. Fleeing with 400 of his troops, only he and one other soldier managed to make it to safety alive.

It was Chhay who had been largely responsible for the call to the New York Times.

We met with him in one of his few surviving strongholds, only a mile from the Thai border. His camp was in ruins, testimony to the continued heavy shelling. As we talked, we could hear incoming mortar rounds getting ever closer, and the bark of his guns replying.

It soon became apparent that he could not deliver the Pol Pot interview as promised...he would say "if you meet with Pol Pot..."

Elizabeth and I began to worry that things were falling apart.We also began to suspect that Nate Thayer had somehow managed to put in a fix to keep us at bay.

As the incoming mortar rounds got closer, General Chhay called an abrupt end to the interview, and we were escorted back across the border in a driving rain.

Now we had to report to the TIMES and ABC, which had come on board to get the television rights to our story, that we had failed to see Pol Pot.

The next morning, we awoke with renewed hope that we would get to Pol Pot's camp.

However, as the morning slipped into afternoon, calls to our contacts remained unreturned. We also discovered that Thayer had managed to get a two hour interview the day before with Pol Pot. Thayer and his TV crew were already on the way back to Bangkok.

Elizabeth and Steve were burning up both the hotel and their cellular phones contacting everyone from the State Department to "heavy weights" from Singapore to Phnom Penh.

Meanwhile, ABC had flown a producer, Ray Homer, in from Tokyo to handle our tapes. AP was on standby to process my film and transmit the pictures to New York.

By 5:00 p.m., the handwriting was on the wall.

All attempts to contact either the Thai authorities, or the Khmer were failing. The phones, which had been in constant use, fell silent.

For those of us who know Asia, we got the message...somebody had decided the New York Times was not going to interview Pol Pot.

In this part of the world, nobody likes to say "no." So, they just say nothing. Silence becomes eloquent.

Why did this happen??? Anybody's guess. Nate Thayer may have somehow cut us off at the pass. The Khmer may have decided that the combination of Elizabeth Becker's journalistic skills and Steve Hander's fluency in the language and his knowledge of their culture and history was just more than they could handle.

Whatever the reason, the outcome is that for the Khmer, their hopes of convincing the West that they had mended their ways and deserved support, have been put on hold.

Once again, the mysteries of Southeast Asia remain as inscrutable as ever.