|

An Exclusive Book Preview with RealAudio commentary. A Multimedia Presentation

of

|

|

An Exclusive Book Preview with RealAudio commentary. A Multimedia Presentation

of

|

When Walter Iooss was a teenager in East Orange, New Jersey, he couldn’t imagine that anything would ever replace the joy and intensity of the stickball games that absorbed his summer days. Four decades have passed, and now Steve Fine, Sports Illustrated magazine’s director of photography, calls Iooss the foremost sports photographer of his generation, "a fixture in American journalism to a degree I think people who see the cover of Sports Illustrated don’t know."

They might be forgiven, although Iooss’s shots have graced the cover of Sports Illustrated over 200 times. Half of those readers weren’t even born in 1959 when Walter got his first assignment. He was told to go to Groton, Connecticut to photograph an octogenarian sailor named Arthur Chester, a man who had built a boat with no plans. The picture made the back page. Iooss has built his own craft, four decades long in the making, also with no plans, just an intuitive gift for light and composition, and a restless internal compass that has pointed him back to the basics. In the fall of 1997, the compass pointed him east to the dimly lit ritualistic world of Thailand’s kick-boxers. The Thai retreat proved to be what the photographer hoped cleansing passage back through the "three Walters." Steve Fine’s short-hand term for Iooss’s artistic evolution, an assessment the photographer accepts.

The first Walter is the one who ran along the sidelines, a guerrilla armed with a Nikon focusing short and long lenses with amazing eye-hand coordination, while the old guard sat in the press box with their fixed-focus Graflex’s. He captured action in a way never seen before, and created a new, freer perspective. It was basic journalism but with a difference: extraordinary backgrounds. Iooss realized that while a 1,000 millimeter lens isolated the tennis player, golfer, outfielder, or wide-receiver he was shooting, the right background created the graphics that often clinched the shot.

There was a favorite background he exploited as he morphed into his second, and subsequent, incarnations. Iooss is like Gulley Jimson, the eccentric painter in Joyce Cary’s "The Horse’s Mouth." He never met a wall, especially a curiously-lit one, he didn’t like. "I love walls. If there isn’t one there, I bring one with me." The kind of shots taken by the second Walter evolved from the raw black and whites that are downright sweaty, playful - pure sport - to the color saturated, "posed" action portraits - pure athlete. This Walter began cataloguing walls and other backgrounds in his head, their best light and shadow, and then waited for the right colored, or action to come their way. They always did.

The second Walter matured with his swimsuit work. Ah, the Sports Illustrated swimsuit issues for which the Iooss lens has born fruit, all the riper for the backgrounds. As in the action shots, the portraits of SI’s swimsuit issues reveal an uncanny graphics sense and Rembrandt-like reverence for light and shadow. He sought and found more control in his swimsuit photographs, especially in the early days traveling light with only cameras and beautiful women, without the interference of art directors.

In his wildest dreams, the 16-year-old Walter could not have foreseen such a future as he pulled himself from the stickball field for the trips to Manhattan to attend photography classes. The most memorable featured a model - the first naked girl he’d ever seen. They eye approved. The die was cast. Thank you, Walter.

The third Walter began to emerge in 1982 when he was approached by Fuji film. The teaming unleashed an epic, two-and-a-half-year project to photograph Olympic athletes up to and during the 1984 games. This required a traumatic severing of ties with Sports Illustrated, "my psyche, my life since I was 16," as he put it. He has since re-upped.

During the period of advertising work that followed Fuji, with its emphasis on portraiture and its opportunities for technical control, the intense essays of individual athletes he’d created at the Olympics played on his mind.

In

the fall of 1992, Iooss approached Michael Jordan with the idea of just

such an essay. It would contain both historic and artistic value, he told

the star Chicago Bull, like the old photos of Elvis, the young Muhammad

Ali. Jordan agreed. The results show the god of basketball in full flight

and, perhaps more importantly, as an earthling, a human after all, amid

the trappings of the upper-class athlete. Walter’s studies of Michael Jordan

are classics. More than the sum of their parts of f-stop and shutter speed,

they reveal a relationship between artist and athlete, each in top form.

In

the fall of 1992, Iooss approached Michael Jordan with the idea of just

such an essay. It would contain both historic and artistic value, he told

the star Chicago Bull, like the old photos of Elvis, the young Muhammad

Ali. Jordan agreed. The results show the god of basketball in full flight

and, perhaps more importantly, as an earthling, a human after all, amid

the trappings of the upper-class athlete. Walter’s studies of Michael Jordan

are classics. More than the sum of their parts of f-stop and shutter speed,

they reveal a relationship between artist and athlete, each in top form.

The third Walter drew the essence of sport from superstars like Jordan, Cal Ripken Jr., and Ken Griffey Jr., with whom he helped create the books Rare Air, Cal On Cal and Junior. The athletes he chose were self-made, he says, not the product of hype or conceit, and their strength of character shows. Iooss was able to draw out their individualities and capture them on film.

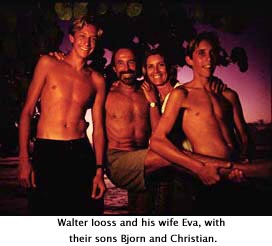

He’s

good with people - a trait his wife Eva attributes in part to a natural

gregariousness, but also to his school days at multi-cultural East Orange

High. His instincts are those of an athlete. He is a gifted one, once a

competitive tennis player. (He once even participated in a doubles match

with Bjorn Borg.) Surfing grabbed him hard, and he follows the waves with

his sons Christian and Bjorn from his home on Eastern Long Island, New

York, to the West Indies and the South Pacific. The surreal beauty of the

sport and the environment moved Iooss toward abstraction in his photographs

and introduced him to another breed of possessed sportsmen whose

souls were ripe for capture.

He’s

good with people - a trait his wife Eva attributes in part to a natural

gregariousness, but also to his school days at multi-cultural East Orange

High. His instincts are those of an athlete. He is a gifted one, once a

competitive tennis player. (He once even participated in a doubles match

with Bjorn Borg.) Surfing grabbed him hard, and he follows the waves with

his sons Christian and Bjorn from his home on Eastern Long Island, New

York, to the West Indies and the South Pacific. The surreal beauty of the

sport and the environment moved Iooss toward abstraction in his photographs

and introduced him to another breed of possessed sportsmen whose

souls were ripe for capture.

Iooss likes to call himself "a photo-investigator - Sherlock Holmes with an eye." Perhaps it’s why he felt a certain anxiety - "I photograph millionaires" - in deciding to go to Thailand. He wanted to rediscover the raw desire of athletes, unadulterated by money or fame, and to document it using a variety of styles. The chiaroscuro black-and-whites from the kickboxing collection place the teenage warriors in the same smoky ring as the young Ali, and the same timeless pantheon as the baseball players he loves the most. But he found a connection between the Thai kickboxers and his friend Michael Jordan, the chance "to be free," Walter says, "to go anywhere you want with no media. It’s almost like you’re welcomed, whereas you’re not a welcomed guest necessarily in a lot of locker rooms or fields. They’re just tired of you. It’s not you personally. They’re just tired of you as a group - the media."

Sadly, the jaded spirit, he has found, is photographable.

His longtime friends call him "coast-to-coast Iooss," and Eva calls her husband "a human Fed-Ex package" for his frenetic travel schedule. He now travels, but with discrimination. The big events like the Super Bowl lost their allure. It’s a more contemplative Iooss, a fourth Walter, the human light meter, who’s bringing forth the land and waterscapes of extraordinary color and clarity that he began taking in the 1970’s.

And,

there’s a recent urge to make collage, to explore graphic design to another

dimension. As with the Jordan and Ali hand prints that serve as this book’s

end papers, Walter reaches further into the realm of mixed media. At the

same time, Walter’s color portraits like some of his track and field photos,

and some of his recent surfing waterscapes, are nearly pure abstract expressions

of form and color.

And,

there’s a recent urge to make collage, to explore graphic design to another

dimension. As with the Jordan and Ali hand prints that serve as this book’s

end papers, Walter reaches further into the realm of mixed media. At the

same time, Walter’s color portraits like some of his track and field photos,

and some of his recent surfing waterscapes, are nearly pure abstract expressions

of form and color.

To hear him talk, a fifth Walter is in the batter’s box. He’s the one who intends to seek out the kids in remote places who make due with window shutters for surfboards, and sticks for cricket wickets, because that’s where the real action is, and has always been.

"It’s always been instinct. In the beginning, I never thought about photographs or photography. I’d get an assignment on a Sunday. It was exciting. You’d tell your friends about it. You’d go to the game to see your heroes, because I was still young and these people were still heroes to me. For years, it went that way. Then, this instinct sort of meshed with my athleticism. My dreams of what sport was, the feeling I get from sport. When I was a Little Leaguer putting my uniform on, it was like Superman putting on his cape. Something came over you. For the moment, if you could squint hard enough in the mirror, maybe I was Mickey Mantle. You were transported into another realm. In high school I would always draw athletes and it was always form: legs, arms, the ballet of sport, bodies in beautiful positions. As time developed, I started to take my fantasies and they’d be manifested in photographs of kids first. Little League and kid’s basketball, which I played every day. I was a complete addict. Those things I enjoyed so much, I’d try to get into the picture somehow, like a swish. There’s a timing of a jump shot. The release. The swishhhhh."

Walter’s passion recalls the words of his gifted predecessor, Henri Cartier-Bresson: "To take photographs is to hold one’s breath when all faculties converge in the face of fleeing reality…it is putting one’s head, one’s eye, and one’s heart on the same axis."

"The real joy of photography is these moments," says Iooss. "I’m always looking for freedom, the search for the one-on-one. That’s when your instincts come out. I’ve been lucky enough to have people hire me to do that. Sports Illustrated never really restricts me. They want me to do what I do. It’s the discovery. It’s still magic."

It seems the ingredients of the Iooss

styles were all there back in East Orange; the awestruck fan taking Duke

Hodges’ name to bat, his eye honed by fast-pitched Spauldings until the

end glow of summer sun beat against the backstop.

Russell Drumm is senior writer at

the East Hampton Star newspaper in New York and author of "In the Slick

of the Cricket." His freelance magazine stories have appeared in GRAPHIS

and SMITHSONIAN magazines.

| Previous

Page |

| Contents | Editorial | The Platypus | Links | Copyright |

| Past Features | Camera Corner | War Stories | Dirck's Gallery | Comments |

| Issue Archives | Columns | Forums | Mailing List |