|

|

|

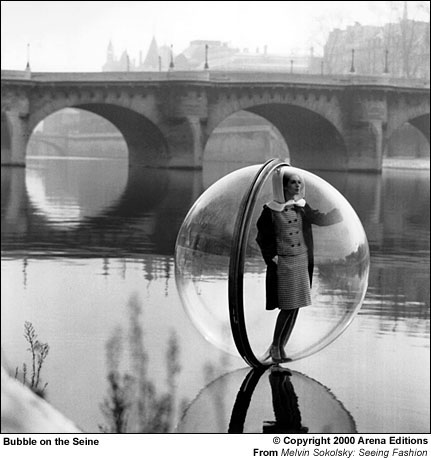

Melvin Sokolsky’s Affinities By Martin Harrison The period between 1955 and 1970 has become widely recognized as a kind of golden age in American magazine culture. In these years the commercial imperative had failed to over-ride the arguably irrational urge to utilize mass-circulation periodicals as a platform for personal expression. Following a time of neglect or indifference, the legacy of many photographers, artists, and designers is again investigated and celebrated. One of the more unusual figures in this pantheon was Melvin Sokolsky. His relatively brief but intense career as a photographer was simultaneously paradigmatic and evidence of how an individual signature could prevail in a commercial environment.

"Astonishingly inventive" and "technically consummate" are typical of the encomiums that Sokolsky’s photographs elicit. The constant stream of frequently audacious ideas that he brought, month after month, to the pages of Harper’s Bazaar certainly bears witness to the claims of fecundity. And the effects he achieved, apparently effortlessly, were the result of tireless experimentation and skillful craftsmanship. He stretched beyond the nominal brief of illustrating clothes, urged on by his tenacious imagination, fired up by an almost child-like thrill with the power of the image, with articulating the body-in-space, and the search to find new ways to make an impact on the magazine page. With no formal training, Sokolsky had to rely on instinct and careful observation for his professional photographic education. He had begun to photograph at the age of ten, using his father’s box camera. His father kept a family album that included old photographs of himself at the ages of five, ten, and fifteen; for Melvin it was disturbing, because each print had a different palette: "I could never make my photographs of Butch the dog look like the pearly finish of my father’s prints, and it was then that I realized the importance of the emulsion of the day." To be a photographer he knew he would have to grasp not only camera techniques but also the refinements of texture and finish, as well as spatial concepts. About 1954, at an East Side barbell club, he met Bob Denning, who was assistant to an established advertising photographer, Edgar de Evia: "I discovered that Edgar was paid $4000 for a Jell-O ad, and the idea of escaping from my tenement dwelling became an incredible dream and inspiration." Technical information avidly gleaned from the Condé Nast book, The Art and Technique of Color Photography, was augmented by de Evia’s answers to the "thousands of questions" Sokolsky posed. Eventually "Edgar either got bored, or I asked too many questions," and these visits constituted the sum of Sokolsky’s technical teaching. Unsurprisingly, his first attempts at photography used a lot of diffusion, in imitation of the Tissot-like effects favored by de Evia. The photographer Ira Mazer passed on a small assignment, and Sokolsky began in this way, gradually building up a portfolio by making the best out of routine advertising assignments. It was about this time, while visiting William Helburn’s studio, that he met a model named Button, his future wife and a central figure in his life and career. Thereafter, his progress was swift. If Sokolsky’s drive and energy supplied the chutzpah to launch his assault across the Bazaar’s Madison Avenue threshold, he needed something more tangible if he was to hold down the job. The core of what he had to offer was innate. It was, apparently, already evident in his behaviour as a child, when he disturbed adults with his habit of holding both hands up to his face, thumbs at right angles, framing the scenes he witnessed like a budding film director: "They became so alarmed as I lined up people at the table, that they eventually took me to an optician, figuring there was a problem with my eyesight." The desire to come to terms with reality by transforming it into images, and the fascination with placing people in spatial relationships, were to pay off later. The precocious sensitivity to lighting and environmental ambience has stayed with him to the extent that (almost, one senses, with embarrassment) he recognizes that he is profoundly distracted in a meeting if the people in a room are arranged and lit in a disconcerting manner. |

|

Order

the Seeing Fashion book

from the Arena Editions website. |