|

|

|

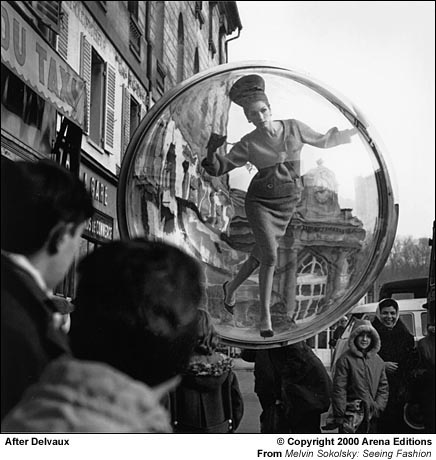

Melvin Sokolsky’s Affinities By Martin Harrison When Sokolsky began to contribute to Harper’s Bazaar in 1959, the magazine had recently dispensed with the services of Alexey Brodovitch, the Russian art director who had been its guiding visual force since 1934 and guru to many of America’s leading photographers. As the Fifties wore on, Brodovitch–formerly the insatiable promoter of the new–was riding on his reputation; though never less than elegant in its presentation, the magazine appeared to run out of fresh ideas. The Hearst organization looked enviously at Esquire, where a young art director, Henry Wolf, was a key member of a team that was producing a lively magazine that offered a more contemporary insight and Wolf’s innovative layout and typography to match. A high fashion glossy was evidently not the same as a men’s general interest title, but Wolf was soon poached by the Bazaar. He was new and determined to make changes. Of the established photographers, some, like Richard Avedon and Lillian Bassman, were unassailable, but Wolf was aiming to introduce more variety. He began to sign up photographers with distinctive new visions, from the oblique lyricism of Saul Leiter to the eye-catching devilment of Melvin Sokolsky. Sokolsky’s interests devolved, like most great fashion photographers, on the woman in front of the camera, rather than the illustration of garments. From childhood, the contact with great paintings in the museums and galleries of New York was a seminal influence: besides his abiding love of Surrealism, there were less usual inspirations, such as the interior spatial effects of Velasquez, and of the Flemish masters Van Eyck and Van der Weyden, and the disturbing subject matter of Bosch and Brueghel. Velasquez’s device of including his self-portrait in the open doorway in the background of "Las Meninas" would eventually recur in a series of Sokolsky’s fashion photographs: by photographing into a mirror, the photographer substituted himself for the painter, the enigmatic presence and hint at voyeurism intensified by the pared-down compositional elements (pages 148-149, 192). For all Sokolsky’s ingenuity, the fundamentals that drove his work and inspired its endless variety were his fascination with female form and gesture, and he cites specifically the paintings of Balthus as having led him to understand that this was his métier (page 151). He says that in every fashion photograph "I tried to show the gesture of the unclothed body beneath the garment: I wanted it to be as if the clothes did not exist. For me, if the merchandise is more important than the woman, then it’s not a good photograph. The only times that the clothes ever interested me were when they suited the woman wearing them: ideally, nothing should look store-bought." In the delicately-poised tussle for supremacy encountered in the business of producing a fashion magazine, Sokolsky generally found it difficult to convey his somewhat alternative agenda to the fashion editors. They in their turn had ambitions to teach this young Vulgarian (an epithet photographer Louise Dahl-Wolfe attached to him early on) all about fashion: "But what they didn’t realize was that Chanel, for example, ultimately loved women, and that in her designs she tried to make new clothes appear worn-in." In analysing and experimenting with gesture, Sokolsky instructed models to turn the palms of their hands towards the lens–a deliberate flouting of the prevailing Renaissance norms of elegance. It is clear from his early magazine work that he was rebelling against what he saw as fashion’s over-riding tendency to follow a trend: "I was instinctual in my approach, and all I had to offer at first was irreverence." |

|

Order

the Seeing Fashion book

from the Arena Editions website. |