Nash

Editions: Fine Art Printing on the Digital Frontier At

a time when millions of homes and offices are equipped with inexpensive,

high-quality printers linked to equally affordable computers and scanners,

it is easy to forget that little more than a dozen years ago digital

imaging and printing were still in their infancy. The prospect of

a high-resolution fine art print that could rival traditional photographic

printmaking in terms of aesthetic value and longevity was still a

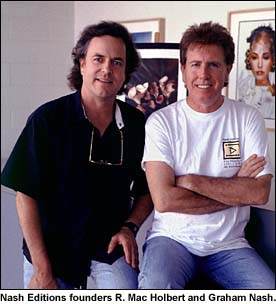

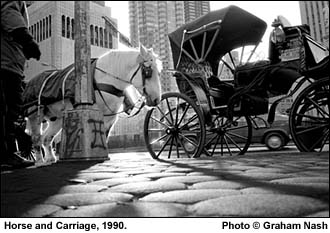

dream being pursued by only a Conceived in 1989, Nash Editions is now widely recognized as the premier fine art digital print studio in the country. The extraordinary body of work produced at Nash Editions represents the entire spectrum of artistic involvement in digital imaging since the medium first became viable in the late 1980s, from highly manipulated images composed in the computer or on a digital scanner to straight photography that has been printed digitally from scans of the negative. After early skepticism, many artists - including, for example, David Hockney, whose experiments with photography and traditional fine art printmaking are well known, and Robert Heinecken, who, among others, pioneered techniques that blurred distinctions between photography, painting, and other fine arts - have embraced the medium and are actively engaged in developing its potential. At Nash Editions, these artists range from Darryl Curran, who creates images he calls scanograms - digital ink prints from ephemeral assemblages constructed on a flatbed scanner - to Nash, who shoots black-and-white photographs but has printed digitally for well over a decade. Concurrent with his music, Nash has built a parallel career as a photographer, world-class photography collector, and digital imaging pioneer. Inspired by his father, who was an amateur photographer, Nash has been taking pictures since the age of 11, and has been a serious photographer throughout his life. I first met Nash at his Los Angeles home in 1990, when I was asked to write a magazine feature about an imminent Sotheby's sale of a large portion of his personal collection of vintage and contemporary photographs. In 1971, not long after his move to the United States from his native England, Nash had quietly begun to collect photographs, hunting in galleries and antique shops while on his many travels with Crosby, Stills, and sometimes Young. "The first photograph I ever bought," he recalls, "was a 1962 image by Diane Arbus - Boy with a Toy Hand Grenade in Central Park. It spoke to me directly about the fact that if we did not teach our children a better way of dealing with their fellow human beings, then our very future was at stake." By 1990, Nash's collection had grown to more than 2,400 prints, including works by Sir John Herschel, Julia Margaret Cameron, Paul Strand, Lewis Hine, Ansel Adams, Edward Weston, Weegee, Henri Cartier-Bresson, and many other major photographers.

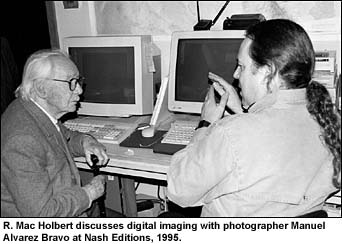

Nash's journey toward digital technologies had in fact begun much earlier. In the late 1970s, Nash's tour manager, R. Mac Holbert, had computerized the band's accounting system. Later he began to experiment with scanning images for tour itineraries. "That," Holbert recalls," led to the idea of creating something of a more artistic nature." The initial impetus for the effort was Nash's desire to scan and print his own black-and-white photographs. "I started with a Thunderscanner," Nash says, "which was a small scanner head that you put into an Apple Dot Matrix printer in place of the ink cartridge. The item to be scanned was fed into the printer--just like loading paper into a typewriter--and special software activated the print head, which scanned the paper line by line. I also had some very primitive manipulation software called Digital Darkroom. It was fun, but when I got serious about it, I found that there was no way to get them off the screen. I tried everything - photographing the screen, thermal prints, wax prints. There wasn't a lot available in those days, and this was in 1987, 1988." Their search led them to UCLA's JetGraphix, an experimental program begun by UCLA professor of design Mits Kataoka. On one of Kataoka's trips to Japan to look at new technologies, he saw a new Fujix printer at the Fuji factory. Fuji later donated three of the machines to UCLA, which formed the basis of JetGraphix. Open to the public, JetGraphix may well have been the first digital output center in the world. When Nash and Holbert arrived in 1989, the Fujix machines were being run by John Bilotta (a printer and production manager at Nash Editions since 1992). "At first we saw a commercial use for them," says Bilotta, "printing posters and other graphic materials. But soon a number of fine artists began to use them." Early attempts to print Nash's photographs were encouraging, and yet not wholly satisfying, particularly with regard to resolution. "They were also very fugitive," Holbert says. "JetGraphix was more of an experiment with the technology. It never really made that leap from the technology to the world of art."

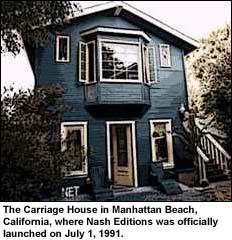

Prompted by his friend Joni Mitchell (with whom he once lived and who was the inspiration for Nash's "Our House"), Nash accepted an invitation to show his own photographs for the first time in a series of exhibitions in Japan sponsored by the Parco Gallery in Tokyo. By now, Nash had installed the Iris printer in a small carriage house in Manhattan Beach. Boulter lived upstairs, and printer and scanner David Coons came in at night to continue to adapt the machine and print the Nash show. The exhibition was a success, touring nineteen galleries in Japan. (Coons, who now runs his own scanning business in Manhattan Beach using the world's largest flatbed scanner, developed with assistance from Nash Editions, also printed Nash's first limited edition portfolio.) "Graham's show was printed," Holbert recalls, "and the machine was just sitting there. I had grown tired of being on the road. I had been spending a lot of time away from my family. I was looking for a way to get back to where I started as a photographer twenty years earlier before I got kidnapped by rock and roll. I said to Graham, "You've just begun this very expensive hobby. Why don't we create a business so that other people can benefit from it? We're getting great reviews, and people are really responding to the prints. Let's give it a shot." Nash's passion for the project and his ability to finance the company allowed Nash Editions to grow slowly, developing proprietary software and perfecting a unique approach to fine art digital imaging and printing. Today Nash Editions clients include artists such as Pedro Meyer, Peter Alexander, William Claxton, Francesco Clemente, Eileen Cowin, Elliott Erwitt, Carol Flax, Allen Ginsberg, Robert Heinecken (another early experimenter at JetGraphix), David Hockney, Robert Glenn Ketchum, Douglas Kirkland, Mark Klett, George Krause, Martina Lopez, Danny Lyon, Sally Mann, Joyce Neimanas, Jenny Okun, Olivia Parker, Marc Riboud, Jamie Wyeth, and many others. From the beginning, Holbert and Nash sought to work one-on-one with artists to make limited edition prints in the manner of a traditional fine art print atelier. Many of the artists in the Nash Editions fold have worked at the studio for years, expanding their own art as Nash Editions has pushed the limits of the technology. "In the last decade," says Holbert, "we have been able to refine the tools, to refine the process so that we can in a fairly seamless fashion allow artists and photographers to better realize with less resistance their vision on paper. Our goal has been to lower that resistance in every way possible - in terms of the technology, the question of permanence, and the general acceptability of the whole process to collectors and museums."

The battle for acceptance of color photography as a viable art form had only been won definitively in the decade before Nash and others began their experiments with digital printing. "We've had to fight on several fronts," Nash says. "First, to entice artists to utilize a brand-new tool that they may not be familiar with. Second, gallery owners were saying that they weren't sure they could hang the work and sell it. And third, on the front of curators to collect and exhibit the work at major institutions." A large part of the struggle for the acceptance of the digital print as a legitimate piece of art has involved issues of permanence. The earliest Iris prints had a display life of only two to three years. By the mid-1990s, the longevity of Iris prints made with organic water-based ink sets was comparable to that of Cibachrome, with an estimated display life of twenty to twenty-five years. "About four years ago," says Holbert, "a new generation of ink-sets appeared on the market. Nash Editions was the test site for one, American Ink Jet's Pinnacle Gold. We helped to develop it, and we continue to use it today. Color display life is estimated at sixty-five to seventy-five years; the black-and-white estimate is 125 years."

Nash, Holbert, and their associates were the first to adapt the Iris ink-jet printer for the purpose of producing fine art prints. Many others soon followed, and for the first decade of fine art digital printing (roughly the 1990s), it remained the backbone of the medium. It was the first printer that could output a large image - 34 inches by 46 inches - at high, continuous-tone resolution. That remained true into the mid-1990s, and until more recently it was the only printer of this kind that could accept a wide range of substrates, from fine art paper to silk and even metal. Other technologies have now overtaken the Iris ink-jet printer, and once again Nash Editions is at the center of efforts to move the medium forward. Last year, Nash Editions participated in a groundbreaking collaboration with Epson America, Inc. Called Epson's America in Detail, the project was intended to showcase Epson's state-of-the-art printers and inks. Epson commissioned photographer Stephen Wilkes to create a "millennial portrait of the United States" by traveling more than 20,000 miles across the United States in search of iconographic images of American life and landscape. Wilkes chose subjects that would not only reflect his interest in color and scale, but that would also present a unique printing challenge in each image. Nash Editions was invited to create prints using the 44-inch-wide format Epson Stylus Pro 9500, which prints at 1,440 dpi, using three distinct dot sizes. The result is a print of unprecedented quality that holds up beautifully under as much as 2,000 lux. "At this point in time," says Holbert, "the only new technology that Nash Editions has chosen to pursue is the print and ink technology developed by Epson, largely due to permanence issues." Over several months, Nash Editions worked with Wilkes and Epson to create forty large-scale color prints, showcased in an exhibition that traveled earlier this year to New York, Chicago, Los Angeles, and San Francisco. Henry Wilhelm, in attendance at the New York and Los Angeles events, estimates that under appropriate conditions the Nash Editions Epson prints may last as long as 200 years - truly an astonishing achievement in color printing. The project also demonstrated a strong and promising commitment on the part of Epson to photographers and artists, rather than only to the specialized industries for which many of these new technologies are first developed.

For Nash, as for Holbert, the graphics and communications tools of the computer age must always be tied to human values. "I've never been afraid of using any tool that I could find," Nash says, "that would enable me to get my thoughts from my head down into some physical reality as soon as possible. And this digital world and the digital revolution that's going on around it is a very exciting one. It doesn't matter to me how you get there. It only matters to me what the intrinsic value of the image is for your own particular soul."

Back to the Contents Page |

||||||

handful

of visionaries. Among those early digital pioneers were rock musician

Graham Nash and friend and former Crosby, Stills, and Nash road manager

R. Mac Holbert. Together, in 1991, the two founded Nash Editions,

the first fine art digital print studio in the world.

handful

of visionaries. Among those early digital pioneers were rock musician

Graham Nash and friend and former Crosby, Stills, and Nash road manager

R. Mac Holbert. Together, in 1991, the two founded Nash Editions,

the first fine art digital print studio in the world.  For

years, Nash had sponsored a traveling exhibition of work from his

collection as an educational outreach to schools and galleries, but

by the time I met him in 1990 he had decided to take his photographic

endeavors in a new and relatively unknown direction: digital printing.

The Sotheby's sale brought in $2.17 million, at the time the highest

price ever paid for a private photographic collection. A portion of

the income from the sale was donated to the Los Angeles County Museum

of Art, and a gift was also made to the J. Paul Getty Museum. Most

of the proceeds from the sale, however, went into the development

of Nash Editions. The studio's first project was a limited edition

portfolio of sixteen Iris prints of photographs by Nash. The first

fine art digital print portfolio ever produced, one of sixteen such

portfolios sold at Christie's in April 1998 for $19,500.

For

years, Nash had sponsored a traveling exhibition of work from his

collection as an educational outreach to schools and galleries, but

by the time I met him in 1990 he had decided to take his photographic

endeavors in a new and relatively unknown direction: digital printing.

The Sotheby's sale brought in $2.17 million, at the time the highest

price ever paid for a private photographic collection. A portion of

the income from the sale was donated to the Los Angeles County Museum

of Art, and a gift was also made to the J. Paul Getty Museum. Most

of the proceeds from the sale, however, went into the development

of Nash Editions. The studio's first project was a limited edition

portfolio of sixteen Iris prints of photographs by Nash. The first

fine art digital print portfolio ever produced, one of sixteen such

portfolios sold at Christie's in April 1998 for $19,500.  During

one visit, Bilotta informed Nash that Fuji would soon cease to support

the generation of Fujix machines used at JetGraphics. He recommended

that Nash and Holbert contact Steve Boulter, then a national sales

rep for Iris Graphics. Boulter introduced the pair to the Iris 3047,

a four-color ink-jet printer developed for the commercial printing

industry to make high-resolution pre-press proofs. "Mac and I

instantly knew what the possibilities were with this machine, that

it could be adapted into something that could make art." Nash

bought his first Iris 3047 in 1989 for $123,000 and set about customizing

it with assistance from Boulter and experimenting with various substrates,

mostly French Arches and Rives watercolor paper.

During

one visit, Bilotta informed Nash that Fuji would soon cease to support

the generation of Fujix machines used at JetGraphics. He recommended

that Nash and Holbert contact Steve Boulter, then a national sales

rep for Iris Graphics. Boulter introduced the pair to the Iris 3047,

a four-color ink-jet printer developed for the commercial printing

industry to make high-resolution pre-press proofs. "Mac and I

instantly knew what the possibilities were with this machine, that

it could be adapted into something that could make art." Nash

bought his first Iris 3047 in 1989 for $123,000 and set about customizing

it with assistance from Boulter and experimenting with various substrates,

mostly French Arches and Rives watercolor paper.  The

current revolution in digital printing can be compared in some ways

to the postwar boom in traditional printing that took place in the

United States and Britain, when studios like Universal Limited Art

Editions (U.L.A.E.), Tamarind, Gemini G.E.L., and Tyler Graphics radically

renewed and transformed traditional printmaking processes in terms

of complexity as well as scale. Those efforts, however, were built

on centuries of tradition. Prints may not have been as highly valued

as paintings, but there was no need to fight for their acceptance

as fine art. That was emphatically not the case with digital prints

or with art made or perfected with computer technology. As critic

A. D. Coleman has written, "Today . . . photography stands permanently

ensconced in the pantheon of the arts, while a multitude of works

generated via computer and proposing themselves as art are presented

for our consideration; and, both appropriately and ironically, photography's

shifting of the ground rules for acceptance into the territory of

art serves as the most frequent analogue in the debate over the claims

for the existence (actual or eventual) of 'computer art.' "

The

current revolution in digital printing can be compared in some ways

to the postwar boom in traditional printing that took place in the

United States and Britain, when studios like Universal Limited Art

Editions (U.L.A.E.), Tamarind, Gemini G.E.L., and Tyler Graphics radically

renewed and transformed traditional printmaking processes in terms

of complexity as well as scale. Those efforts, however, were built

on centuries of tradition. Prints may not have been as highly valued

as paintings, but there was no need to fight for their acceptance

as fine art. That was emphatically not the case with digital prints

or with art made or perfected with computer technology. As critic

A. D. Coleman has written, "Today . . . photography stands permanently

ensconced in the pantheon of the arts, while a multitude of works

generated via computer and proposing themselves as art are presented

for our consideration; and, both appropriately and ironically, photography's

shifting of the ground rules for acceptance into the territory of

art serves as the most frequent analogue in the debate over the claims

for the existence (actual or eventual) of 'computer art.' "  Advancements

in the composition of ink sets and substrates have finally given digital

prints a longevity that has made them attractive for collectors and

museums (not to mention the artists themselves). The MoMA purchase

of large-scale Iris prints by Chuck Close, the inclusion of several

Iris prints in the Guggenheim's Robert Rauschenberg retrospective,

and more recent exhibitions of Iris prints by well-known photographers

such as Annie Liebovitz and others demonstrate a major positive shift

in attitudes toward the medium. Linked to this is a growing awareness

of the superiority of digital photographic output over traditional

prints made in the darkroom. "It's not an overstatement,"

says Henry Wilhelm, founder of Wilhelm Imaging Research and one of

the world's leading authorities on the stability and preservation

of traditional and digital color photographs, "to claim that

in the digital era, color photography has finally arrived. The print

made by the enlarger is dead. With an enlarger you can control lightness,

darkness, and overall color balance, but you have no control over

color saturation, and no real control over contrast. Those are incredible

limitations. Modern color photography appeared in 1935 with the introduction

of Kodachrome, and these issues of color reproduction have been a

struggle ever since. It's in this era, through Photoshop and the Iris

printer, that we've finally been given full control. I think it would

be a mistake, however, to limit discussion of digital output to Iris

prints. A number of artists working in straight traditional photography

have begun to output digitally directly to color photographic paper.

That gives you the full tonal scale and good color reproduction with

full digital control. Digital output on the home desktop printer can

also provide good results."

Advancements

in the composition of ink sets and substrates have finally given digital

prints a longevity that has made them attractive for collectors and

museums (not to mention the artists themselves). The MoMA purchase

of large-scale Iris prints by Chuck Close, the inclusion of several

Iris prints in the Guggenheim's Robert Rauschenberg retrospective,

and more recent exhibitions of Iris prints by well-known photographers

such as Annie Liebovitz and others demonstrate a major positive shift

in attitudes toward the medium. Linked to this is a growing awareness

of the superiority of digital photographic output over traditional

prints made in the darkroom. "It's not an overstatement,"

says Henry Wilhelm, founder of Wilhelm Imaging Research and one of

the world's leading authorities on the stability and preservation

of traditional and digital color photographs, "to claim that

in the digital era, color photography has finally arrived. The print

made by the enlarger is dead. With an enlarger you can control lightness,

darkness, and overall color balance, but you have no control over

color saturation, and no real control over contrast. Those are incredible

limitations. Modern color photography appeared in 1935 with the introduction

of Kodachrome, and these issues of color reproduction have been a

struggle ever since. It's in this era, through Photoshop and the Iris

printer, that we've finally been given full control. I think it would

be a mistake, however, to limit discussion of digital output to Iris

prints. A number of artists working in straight traditional photography

have begun to output digitally directly to color photographic paper.

That gives you the full tonal scale and good color reproduction with

full digital control. Digital output on the home desktop printer can

also provide good results."  Sensitized

to the stigma that has sometimes been attached to creativity related

to computers, Nash and Holbert, along with all of the artists who

work with Nash Editions, are quick to point to the technology as another

set of tools, a broader palette. "One of the misconceptions about

this medium," says Holbert, who conducts workshops and lectures

frequently on digital imaging, "is that if you can buy the equipment,

you're immediately a fine-art printmaker. There are reportedly some

two hundred and fifty digital printmakers in the United States, but

much of what we've seen wouldn't make it to our clients as a proof.

The most important tool is still your own eye. You're going to be

wrong almost every time if you allow the technology to make decisions

for you."

Sensitized

to the stigma that has sometimes been attached to creativity related

to computers, Nash and Holbert, along with all of the artists who

work with Nash Editions, are quick to point to the technology as another

set of tools, a broader palette. "One of the misconceptions about

this medium," says Holbert, who conducts workshops and lectures

frequently on digital imaging, "is that if you can buy the equipment,

you're immediately a fine-art printmaker. There are reportedly some

two hundred and fifty digital printmakers in the United States, but

much of what we've seen wouldn't make it to our clients as a proof.

The most important tool is still your own eye. You're going to be

wrong almost every time if you allow the technology to make decisions

for you."