|

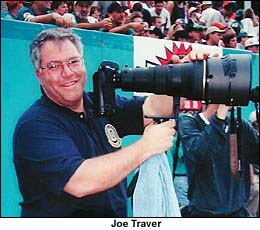

Joe

Traver died last month. Joe

Traver died last month.

Let's get this hard part out of the way - he killed himself. He had

been arrested in his home, on charges of sodomy, based on the testimony

of a young man he had befriended, who was serving time in jail. In the

process of the arrest, by black-uniformed members of the sheriff's department

swat team, one of the deputies accidentally shot and wounded himself.

As a result of the furor surrounding the shooting, it became a big story

in Joe's home market of Buffalo.

His friends and colleagues photographed him on a "perp walk,"

and one even went so far as to ask Joe to arrange TV coverage of his

own trial. It was just too much for a person who had prided himself

on reaching out to his chosen profession of photojournalism all of his

life. So he took some pills and ended his life.

In the days following, there was a torrent of email on the National

Press Photographers' discussion list. First, about the incident, then

his death. Finally, there was a note from a bewildered young photographer

that asked, "Who was Joe Traver, anyway?" Let me try toanswer

this question.

If you were a member of the National Press Photographers Association,

or took part in any of their educational programs, or were assigned

to the 1996 or 2000 Olympic Games, or covered professional football,

or were simply a young photographer looking for a helping hand, the

chances are your life was affected by Joe Traver.

He got his start in 1977 as a staff photographer for the Buffalo Courier-Express,

where he worked until 1982. When the paper folded, he decided to start

freelancing, working for, among others, Reuters, The New York Times,

Sports Illustrated, Gamma Liaison, and Black Star. His clients over

the years included The LA Times, The New York Post, Newsday, USA Today,

The Houston Post, The Boston Globe, Time, Newsweek, Business Week, Forbes,

Fortune, and National Geographic.

In 1993, he took time out to get a master's degree in labor and policy

studies at the State University of New York. He was also the Buffalo

Bison's official photographer from 1981 to 1991. In 1989, he was feted

at the Pro Football Hall of Fame in Canton, Ohio, as Pro Football Photographer

of the Year - this followed his winning "Photo Of The Year,"

which showed jubilant Buffalo Bills fans after the Bills beat the New

York Jets in overtime during an AFC East playoff game.

It was, however, Joe's tireless efforts on the part of the group he

loved the most, The National Press Photographers Association, that is

his true legacy. He joined the NPPA while a student at Syracuse University

in 1973. He had a deep and abiding belief in the importance of education

for photojournalists, which culminated in his co-founding the NPPA Northern

Short Course that provided seminars and workshops for photographers.

In 1993, after serving seven terms on the NPPA Board of Directors, he

was elected National President of the organization, and helped to steer

the NPPA through its 50th anniversary year.

In 1996, he was selected as the Deputy Photo Manager for the 1996 Atlanta

Olympic Games, and returned to coordinate all photo coverage for the

2000 Olympic Games in Sydney, Australia.

These are the dry facts. What they do not tell you is how hard he worked

during all these years, not only to excel at his profession, but how

much time he put into helping other photographers. As Arnold Drapkin,

who worked with Joe for years as Director of Photography at Time, then

helping him at the Olympics has written, "As a mentor to many,

along with photography, he taught those old-fashioned virtues of hard

work, perseverance, loyalty, and team work. Still photography had a

champion at the Olympics. He worked hard to maintain and improve the

conditions that enabled photographers to make their memorable images.

The NPPA was truly a second career to him, and education, professional

ethics and the welfare of his peers were his priorities."

In an open letter to his friends, written just before taking his life,

Joe said, "I have had a great life. I have been to the mountain

with Muhammad and have seen the other side. I have had the opportunity

to do more than most, and have been blessed with a plethora of the best

friends on earth. It has been a priority of mine often and frequently

to utilize assistants and help a few others to see the joys and hard

work of photography. The NPPA has been my second career for 24 years.

I have firmly believed the adage that it is important to give back to

the career that has helped you so much." In his final words, he

said, "Please remember me as the big guy with a

smile and open heart."

Well, we do, through the tears.

|