You

don’t have to ask Jay Maisel if he’s a Native New Yorker,

you just know. It’s not the accent, or the way he dresses. What

gives it away is attitude. Not his attitude, just attitude, that unique

New York quality that is difficult to completely define. You just

know it when you see it.

You

don’t have to ask Jay Maisel if he’s a Native New Yorker,

you just know. It’s not the accent, or the way he dresses. What

gives it away is attitude. Not his attitude, just attitude, that unique

New York quality that is difficult to completely define. You just

know it when you see it.

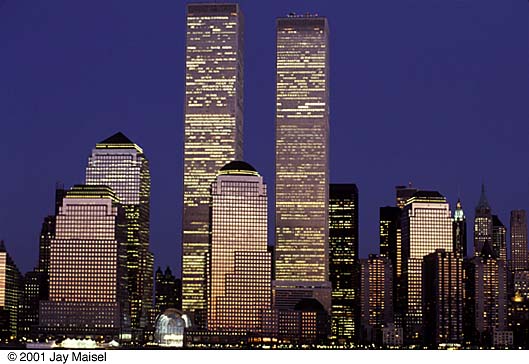

One of the reasons that Jay loved to photograph the twin towers of

the World Trade Center was that, for him, they also had attitude.

“ A lot of people have asked me if I liked them visually.”

he said in a recent conversation “Yes, I think they were very

New York, very in your face. They were a wonderful symbol; they were

without a doubt the quintessential New York landmark, much more than

the Empire State Building because of their ‘twin-ness’,

and they were just a wonderful graphic symbol.”

Another

cause of his devotion to these towering expressions of New York brashness

and self-confidence is that for the thirty-five years that he has

occupied the former bank building that is his studio, office and home

they were the bookends of his day. In the middle of the sixties when

he moved in they were under construction. “I watched them grow

to full size. I watched them take the rigging down, take the cranes

down, put up the mast, and it was the first thing that I would see

when I woke up in the morning because I positioned my bed so that

I could just look out of the window and see the World Trade Center,

and when I went to bed at night, after the lights went out, I would

look out and see them.”

You

have to have lived in the city to fully understand what the buildings

meant to New Yorkers. If you emerged from almost any subway station

on the West Side below 34th street you would use them to orient yourself.

The Empire State Building meant you were heading north, and the Towers

south. The further south you went the more dominant they became, until

they seemed to devour the landscape. The expansive view from the roof

of Jay’s building is that much less breathtaking now than it

was on September 10th 2001. It’s not like removing the Eiffel

Tower from Paris or Big Ben from London. It’s more like taking

the Mount Ranier from the backdrop of Seattle. More so, because they

were a part of the city, and unlike these other landmarks they were

the workplace of thousands upon thousands of people. Jay expresses

his, and New York’s loss by saying: “I think that if people

weren’t in them it wouldn’t matter worth a shit. We’d

rebuild them and that would be the end, but I think the pain of losing

all those people is what we remember most, long after we forget the

visual quality of the World Trade Center and figure out what kind

of memorial or not memorial, or build them or not build them. I found

myself crying at inopportune times, and I was afraid that somebody

was going to ask me ‘Did you lose somebody?’ and the answer

was ‘Nobody I knew, but I lost everybody.’ We all lost everybody.”

As the city’s shock and numbness slowly began to subside anger

started to take its place. Home made posters of Osama Bin Laden overprinted

with cross hairs and the slogan “Skilled Snipers Wanted”

appeared taped to lampposts and mailboxes. Muslim taxi drivers put

the largest Stars and Stripes in their cab windows that they could

and still see to drive. Jay’s attitude to the perpetrators is

forceful but measured:

“A friend of mine wrote something. He was down there [at Ground

Zero] cutting steel, and I can’t paraphrase it, but basically

he said the danger is becoming ‘them’. At the same time

I don’t feel like this is a time for love, peace and forgiveness.

We’re going to have to tread a thin line, and I hope to God they

don’t screw it up again.”

As

the owner of probably the finest collection of photographs of the

World Trade Center in existence Jay feels that there is a need to

do a book and exhibition that doesn’t dwell on the inferno, but

essentially acts as a memorial, not only to the people who died but

also to the buildings themselves. At this moment these plans are in

progress, and he is looking for corporate sponsorship to ensure that

work is brought to the widest possible audience. I got the sense during

our conversation that Jay, like many New Yorkers, is using his plans

for the future to come to terms with the present. New York is a tough

and feisty town that prides itself on its hardiness. Jay Agrees:

As

the owner of probably the finest collection of photographs of the

World Trade Center in existence Jay feels that there is a need to

do a book and exhibition that doesn’t dwell on the inferno, but

essentially acts as a memorial, not only to the people who died but

also to the buildings themselves. At this moment these plans are in

progress, and he is looking for corporate sponsorship to ensure that

work is brought to the widest possible audience. I got the sense during

our conversation that Jay, like many New Yorkers, is using his plans

for the future to come to terms with the present. New York is a tough

and feisty town that prides itself on its hardiness. Jay Agrees:

“There’s a lot of resilience in this town. I remember when

I walked through Washington Square there was one sign that said: ‘You

picked the wrong fucking town to do this.’”

But he cautions that, in a city that until September 11th, 2001 thought

that it had seen everything: “I don’t think that we’ll

ever be the same. I look at my kid. My kid, thank God, it’s like….

I’m not going to try and impress on her what a horror it was,

but I think she knows. She’s not manifesting any symptoms or

anything, but I think she knows.” Jay’s child is one of

the lucky ones. Of all of the catastrophic statistics that have come

out of this disaster one of the most tragic is that the deaths of

the seven hundred employees of Cantor Fitzgerald, it’s entire

workforce, have meant that twelve hundred children in the New York

area are now without a parent. Their loss will be the living legacy

of the horror.

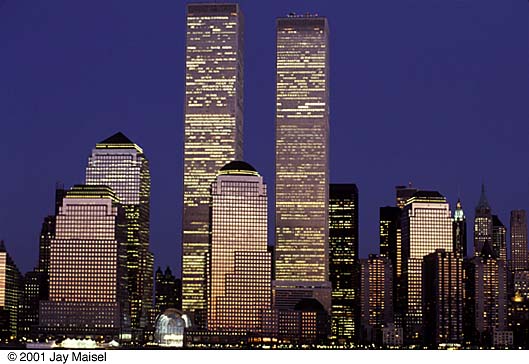

A couple of days after being with Jay I was sitting in the lobby of

a mid-town hotel waiting for one of the guests. On one wall was a

rack of brochures from companies trying to lure tourists to the ephemeral

pleasures of New York sightseeing. As I browsed through these it became

apparent that at least seventy per cent would have to be reprinted.

Each of them prominently featured images of the World Trade Center,

a taste of New York that they can no longer offer. But if the brochures

will have to be redesigned to accommodate the city’s loss, the

images produced over the years by Jay and other talented photographers

will serve as evidence that our memories are correct. Yes these elegant

buildings did exist, yes the elevators did travel at fifty miles per

hour, and yes the Windows of the World was one of the few restaurants

where on certain days you could eat lunch above cloud level. One of

photography’s greatest strengths is to be a guardian of memories,

the incontrovertible proof of times past, especially a time when two

tall buildings symbolized much that is New York.

© 2001 Peter

Howe

You

don’t have to ask Jay Maisel if he’s a Native New Yorker,

you just know. It’s not the accent, or the way he dresses. What

gives it away is attitude. Not his attitude, just attitude, that unique

New York quality that is difficult to completely define. You just

know it when you see it.

You

don’t have to ask Jay Maisel if he’s a Native New Yorker,

you just know. It’s not the accent, or the way he dresses. What

gives it away is attitude. Not his attitude, just attitude, that unique

New York quality that is difficult to completely define. You just

know it when you see it.

As

the owner of probably the finest collection of photographs of the

World Trade Center in existence Jay feels that there is a need to

do a book and exhibition that doesn’t dwell on the inferno, but

essentially acts as a memorial, not only to the people who died but

also to the buildings themselves. At this moment these plans are in

progress, and he is looking for corporate sponsorship to ensure that

work is brought to the widest possible audience. I got the sense during

our conversation that Jay, like many New Yorkers, is using his plans

for the future to come to terms with the present. New York is a tough

and feisty town that prides itself on its hardiness. Jay Agrees:

As

the owner of probably the finest collection of photographs of the

World Trade Center in existence Jay feels that there is a need to

do a book and exhibition that doesn’t dwell on the inferno, but

essentially acts as a memorial, not only to the people who died but

also to the buildings themselves. At this moment these plans are in

progress, and he is looking for corporate sponsorship to ensure that

work is brought to the widest possible audience. I got the sense during

our conversation that Jay, like many New Yorkers, is using his plans

for the future to come to terms with the present. New York is a tough

and feisty town that prides itself on its hardiness. Jay Agrees: