Don

MacLeod: Don

MacLeod:

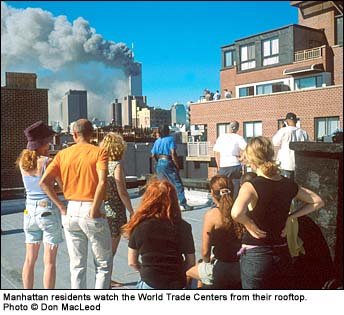

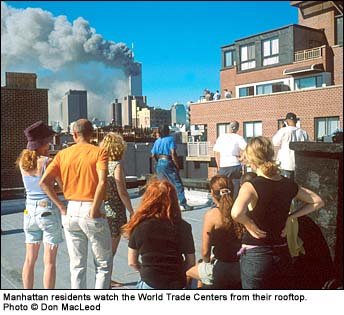

When I heard the news, I grabbed my cameras and ran up three flights

of stairs to the roof of my building in Little Italy. My neighbors

were already there, silently watching the collapse of the South

Tower. There wasn't much to say; we all stood there watching, not

talking. Normally we go the roof for Fourth of July fireworks or

to sunbathe or to have a summertime party. Watching the towers fall

on an otherwise perfect September morning was so incomprehensible

that nobody at the time seemed to realize the enormity of it. The

attack seemed to happen in slow motion. For those us far enough

removed geographically from the site, what we were watching was

surreal. It wasn't frightening or moving. The attack looked like

an almost prim performance of catastrophe. The terrorists wanted

to make an immense show; they certainly had an audience for their

murderous handiwork.

While the rest of New York slowly returned to routine, work continued

around the clock at Ground Zero. Rescuers worked through the clouds

of smoke from still-burning fires and the thick dust raised by every

move they made. The site was lit by portable floodlights brought

to the scene the night of the attack. This shot was taken at 11:00

PM, Sept. 16, five days after the attack. At the time, there was

still hope of rescuing survivors and the list of the missing was

still estimated to be below 5,000. |

|

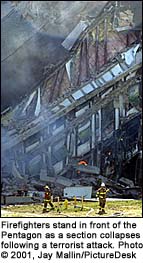

Jay Mallin:

I was at the Pentagon early on, and the photos taken an hour or

so later, when the media had been pushed much further back, don't

convey the destruction of the attack. The Pentagon itself is so

huge, the gap blown in it looks small by comparison. What was

really stunning, standing there, was that there was no sign of

the plane itself. This was a big plane with a lot of local people

in it, people from my neighborhood, and it hit that building so

hard it seems to have vanished into nothing.

|

|

|

|

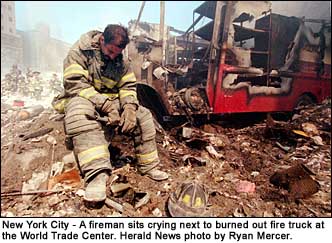

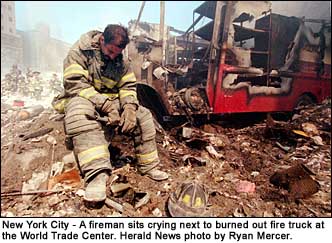

Ryan

Mercer, Chief Photographer, Herald News, Passaic County, NJ

I got caught in a blast of dust 2-3 blocks from Ground Zero. It

swallowed you up, everything went deathly quiet and completely

black. For sixty seconds I had no idea how I was going to get

out. Then I took a lens cleaning cloth covered with a polymer

to breathe through. I found another man in a similar situation,

we walked out together and I brought him to an ambulance. After

I calmed down, I went back in to get my job done.

|

Gilbert

Plantinga:

I went down to the New York State Armory, where they were gathering

missing persons information. The camera crews were there, doing

head-and-shoulders of people holding up flyers pleading for help

for their loved ones. I couldn't help but think that there was little

that I could do for these people with my still photos, but that

the television guys probably weren't doing that much good either.

I had to break through some sort of empathy barrier and become a

part of the scene. |

|

|

Don

MacLeod:

Don

MacLeod: