I love writing.

The pleasure that I get from plucking the right word out of the air

is comparable to knowing that you pressed the shutter at the perfect

moment. However writing is the only pleasure in my life that I constantly

put off enjoying. It's a bit like sex when you're a teenager, you

know you want it, but you can't get up the nerve to call the girl.

I can assure you that every piece that I've written for the Digital

Journalist was completed only hours, sometimes minutes before the

site was put up.

At the moment I'm writing a book with a deadline of April 1st. Whether

the publisher chose April Fools Day deliberately as the final moment

to receive my manuscript I can't say. What I can say is that the opportunities

for prevarication are even greater with a book than with a column.

I will do anything rather than put finger to keyboard, even to the

extent of reading the photojournalism forums on the DJ. It was during

on such moment of evasion that I read a posting from Nigel Parry,

an excellent portrait photographer whose work has graced the pages

of Esquire and other publications. His comments were as follows:

February 2002's TDJ editorial states:

"More importantly, Thomas Franklin captured a moment in history,

just as Joe Rosenthal did. Imagine if the sculptor of the Iwo Jima

memorial, which overlooks the nation's capitol, had decided to depart

from the likenesses in the photograph. The result would have been

to invalidate the image."

My understanding was that the Iwo Jima photo was posed long after

the original flag raising. I believe I read this in an article the

Saturday magazine of the Independent (UK) some years ago.

Surely there were better examples to draw from than one in which the

cultural revisionism took place at the moment the shutter was pressed?

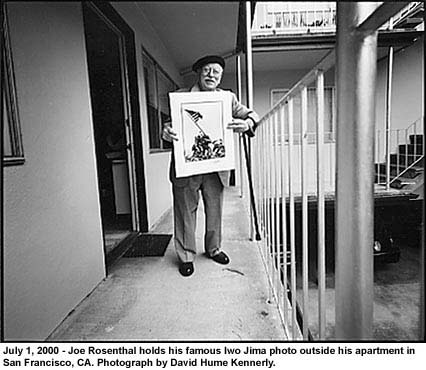

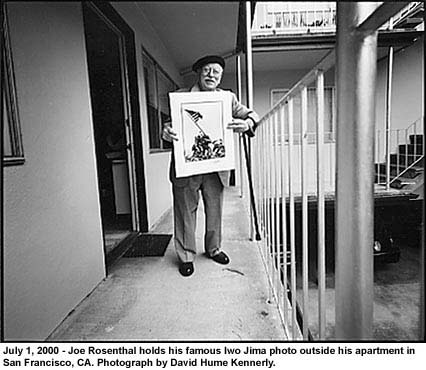

Because the book that I'm writing is about combat photographers I

happen to know a lot about the arguments around Joe Rosenthal's famous

photograph, which incidentally is the most published picture in the

history of photography. Since I also know Joe Rosenthal, who is the

sweetest, most honorable guy you would ever want to meet, it pissed

me off to hear his most celebrated work described as "cultural

revisionism."

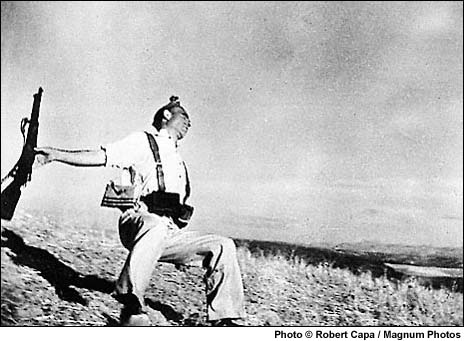

It wasn't more than two days after this that I received a copy of

a piece by Robert Capa's biographer Richard Whelan in which he describes

the extensive detective work that he has done to prove that Capa's

Falling Soldier picture was not set up. Whelan has been involved

in combat himself, although of an academic kind, with the British

journalist and historian Philip Knightly, who claimed in his book

The First Casualty that this photograph, taken in 1936 during

the Spanish Civil War, was a fake.

Oscar Wilde once

said that the pure and simple truth was rarely pure and never simple,

and that is certainly the case with these photographs that rank as

two of the greatest war photographs ever taken. With the Rosenthal

image the full and complete story is this. After four days of intense

fighting on Iwo Jima, Colonel Chandler Johnson, Commander of the Marine

2nd Battalion, ordered a platoon to make the ascent to the summit

of Mount Suribachi and plant the Stars and Stripes, the first time

they would fly on Japanese soil. When the Secretary of the Navy, who

was observing the battle from a ship, decided he would like that flag

as a souvenir Johnson was so incensed that he ordered a another, larger

flag to replace the original, which he intended to keep for the Marine

Corps. Sergeant Mike Strank and his men from Easy Company got the

order to find a larger flag than the original on the justification

that, as Strank put it, "every son of a bitch on this whole cruddy

island can see it."

Rosenthal was convinced that he had missed the main event, the placing

of the first flag that happened earlier on the same day, but shot

one frame of the replacement, plus a posed picture of the men who

had performed the second raising. It was this picture that caused

the controversy. The flag raising photograph hit a nerve with the

public that caused it to be published around the world before Rosenthal

had even seen it. When asked by a fellow correspondent if it was posed,

Joe said yes, thinking that the questioner was referring to the second

frame. The full and fascinating story of the flag is told in the excellent

book Flags of Our Fathers by James Bradley, the son of one

of the flag raisers.

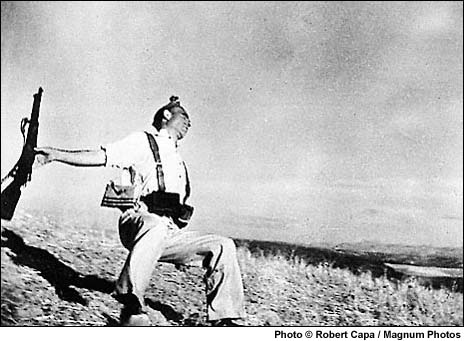

The Capa photograph

is a little murkier. Capa never captioned the photograph, or identified

the dying soldier, and when the picture first appeared in the French

magazine Vu, the caption that accompanied it in the publication did

not state where or under what circumstances the man had been shot.

When I say that Richard Whelan did extensive detective work on proving

the authenticity of the picture I really mean it. He even enlisted

the help of Captain Robert Franks, the Chief Homicide Detective for

the Miami Police Department, who provides compelling evidence that

the soldier in the picture was already dead as Capa shot the frame.

Whelan has even been able to identify the man as Federico Borrell

Garcia who was killed in a battle at Cerro Muriano in September 1936.

Because of this detailed investigation I think that probably the only

person who still believes that the picture is a fake is Philip Knightly.

The thing that I find fascinating about all this is why it is that

there seems to be a need to debunk photographs taken by brave men

under appalling circumstances. After Philip Jones Griffith published

his seminal book on the Vietnam War, Vietnam Inc, in 1971 one

reviewer claimed that the photographs had been shot on sets constructed

at Cine Cita in Rome, using actors as subjects. Where a photographer

would get the money to do this, and why he would want to in the first

place was never explained.

The truth of the matter is that Joe Rosenthal was on Iwo Jima during

was one of the bloodiest battles of the Second World War. Over 100,000

Marines faced off against 22,000 Japanese defenders entrenched in

caves dug deep into the volcanic mountain, with carefully placed intersecting

fields of fire that allowed them to target every square foot of the

tiny island. They made no exceptions for the square feet that Joe

Rosenthal stood on.

The truth of the matter is that Robert Capa's courage as a combat

photographer is indisputable, leading him among other acts of bravery

to accompany the first wave of troops to hit Omaha Beach in Normandy,

the toughest beach landing of the invasion. It was courage that he

displayed throughout his life until his death in 1954 when he stepped

on a land mine in Vietnam.

These two men, one a hard working wire photographer, and the other

the quintessential war correspondent have given the world two images

that stand as symbols of both the horror of war and triumph of the

human spirit over war. That these photographs were produced by men

of courage and integrity is as much a validation of their authenticity

for me as any other evidence that can be produced for or against it.

Even if we didn't know the story behind the Rosenthal photograph and

even if Richard Whelan's detective work had proved to be inconclusive

it would not devalue the importance to our culture that the two icons

have acquired in the last fifty to sixty plus years, for they have

transcended the circumstances under which they were taken. Sometimes

truth, like beauty, is in the eye of the beholder.

©

2002 Peter Howe

Contributing Editor

peterhowe@earthlink.net

Peter

Howe is a former picture editor for the New York Times and Director

of Photography for LIFE magazine. From 1998 until 2000, he was a consultant

and Vice President for photography and creative services for Corbis.