|

A

Reporter's Journal From Hell

by

Joe Galloway

Part Two: Feet on the Ground

Back

in Danang I was introduced to the man I was replacing, Hongkong bureau

chief Charlie Smith who had been on temporary assignment covering the

newly arrived Marines. My quarters would be in the Marine Press Center,

a shabby compound on the banks of the Danang River which in a former

life had been a whorehouse for visiting merchant seamen. There were

two rows of high-ceilinged whitewashed rooms, no air-conditioning, just

ceiling fans that stirred the damp air, a bar and restaurant, and offices

for the Marine Information officers. UPI, AP, Reuters and the three

networks all kept permanent rooms there. There were rooms for visiting

firemen, as well. We all rented battered old jeeps from an enterprising

Chinese jewelry store owner named Kim Chee.

By the time I arrived there were two battalions of Marines assigned

to guard against attacks on Danang Airbase where American Air Force

planes were now flying daily raids against targets in North Vietnam.

More were on the way. Lots more. The battalion commanders were guys

like Lt. Col. P.X. Kelly, who would later become commandant of the Marine

Corps. One of the artillery battalion commanders was Bud McFarlane who

would become an ill-fated adviser to President Ronald Reagan.

My competition in those early days were guys like John Wheeler and Eddie

Adams and Bob Poos of AP. Simon Dring of Reuters. Others who arrived

in due course: UPI photographers Kyoichi Sawada and Steve Northup. Dickie

Chapelle. Col. Bob Heinl, a Marine historian. The Marines contributed

folks like Maj. Mike Stiles, who on one notable evening in his cups

decided to try out a new experimental Browning 9mm pistol in the press

bar and fired off an entire magazine. As bullets richocheted around

the room one intrepid correspondent took shelter beneath the quarter

slot machine. Later he explained, "That machine hasn't been hit yet."

Poos sat calmly at the bar and never moved. There were no casualties.

We

covered every Marine operation in I Corps, including a combat amphibious

assault landing on the Batangan Peninsula to clear the way for establishment

of a Marine airbase at Chu Lai. We

covered every Marine operation in I Corps, including a combat amphibious

assault landing on the Batangan Peninsula to clear the way for establishment

of a Marine airbase at Chu Lai.

On one Marine operation south of Danang a new AP reporter made his debut.

George Esper had arrived from Philadelphia. The operation was already

underway when he landed and he was trying desperately to catch up with

everyone else. We were at the point of the operation, had pulled off

the trail and were sprawled on top of a low hill at the edge of a broad

rice paddy. There were no Americans in front of us. Suddenly a Marine

sergeant yelled, "Who the hell is that?" We looked to see this dark-haired

American splashing out in the paddy scooting across it. We hollered.

He couldn't hear and just kept going. George was now the point man of

the whole operation. He hit the far edge of the paddy and disappeared

into the jungle. Our hearts sank. The Marines began saddling up to go

rescue him or retrieve his body. Two or three minutes later George reappeared

and jumped back into the rice paddy, pursued by an old Vietnamese peasant

woman wielding a hoe. She stopped at the edge, satisfied that she had

repelled the foreign invader. George hooked up with us and when he caught

his breath exclaimed: "That crazy old woman tried to kill me, even after

I told her I was with AP."

My assignment to Danang was almost permanent. I was up there for such

long stretches that the Saigon bureau would send up packages of Vietnamese

piastres to pay the rent and expenses, and bundles of my personal mail,

some of it two or three months old by the time it reached me.

There were firefights, brief violent eruptions of gunfire, mortar and

artillery, air strikes from hovering Marine fighter planes. Occasionally,

but only occasionally, did the Viet Cong hang around. The Marines were

frustrated. The enemy was everywhere and nowhere. In the best traditions

of Muhammed Ali, they danced like a butterfly and stung like a bee.

And then they were gone and very hard to find among the population.

In August of 1965 I had been back in Saigon for a brief visit and was

back on the C-123 bound for Danang. During the first stop, in Pleiku,

I looked out the back hatch and saw South Vietnamese soldiers flinging

dead bodies off a helicopter. I grabbed my pack and camera bag---by

now I had earned enough money, at $10 per picture used by UPI, to buy

myself a Nikonos 35mm underwater camera and two Nikon F black bodies

and a small assortment of lenses---and bailed out.

A South Vietnamese column had been ambushed and chewed up trying to

go to the relief of the Duc Co Special Forces Camp. Another South Vietnamese

Airborne column was marching out of Duc Co bound for Pleiku. I hooked

up with some American 101st Airborne troops who planned to meet up with

the South Vietnamese force. Eventually that meeting took place. I snapped

a few shots of the tiny Vietnamese soldiers led by a huge American major.

Shook hands with the major and introduced myself. His name was Norm

Schwarzkopf. That meeting would come in handy 25 years later in Saudi

Arabia during the Persian Gulf War when Gen. H. Norman Schwarzkopf was

commander in chief.

I spent a week or two around Pleiku and got acquainted with the American

provincial adviser, Col. Ted Metaxis, and his people. There were rumors

of a new, experimental U.S. Army division coming to the Central Highlands

in a few days. There seemed to be a quickening of the pace in this area

and I had a feeling I would be back before long. I headed on back to

Danang and the Marines. For now.

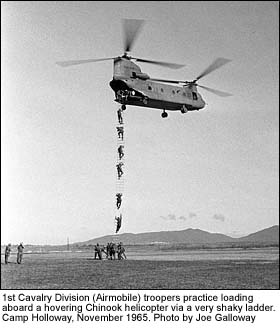

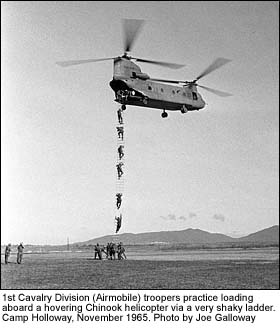

Those new Americans, the 1st Cavalry Division (Airmobile) arrived in

An Khe, the new base they would have to carve out of the jungle, in

early September. I shifted from Danang to An Khe in late September.

The Cav had 435 helicopters in their inventory. They RODE to war. The

Marines walked. They walked so much that I had worn out two pair of

combat boots going along with them in those months. There was a press

tent at An Khe and a jovial major named J. D. Coleman and a Specialist

4 named Marv Wolf who manned it. Another Specialist 4 named Joe Treaster

also worked there. He would later take his discharge in Vietnam and

join The New York Times as a reporter. The Cav also brought along with

them their hometown reporter, a grizzled and, to we 20-somethings, ancient

World War II veteran Marine named Charlie Black of The Columbus (Ga.)

Ledger-Enquirer. We would all go to school on Charlie Black who lived

with the Cav 24/7 and loved what he was doing. Charlie would go out

with a battalion on operations and stay for a week or ten days or two

weeks. When he came back to An Khe he would sit down at a battered old

typewriter and write endless dispatches, single spaced, on onion skin

paper. His stories were full of names and hometowns. He would find a

friendly GI who would frank the letter so it went home airmail for free.

His editor would run every line, because his readers included the wives

and kids of many of the troops. Charlie was supposed to stay two or

three weeks; he ended up staying more than a year that tour. Traded

in his return air ticket for pocket money, slept on the ground or in

the press tent for free and ate a steady diet of C-rations, also for

free. The Cav troops would have happily passed the hat for donations

if Charlie had gone totally broke. They loved him, and the love affair

was mutual.

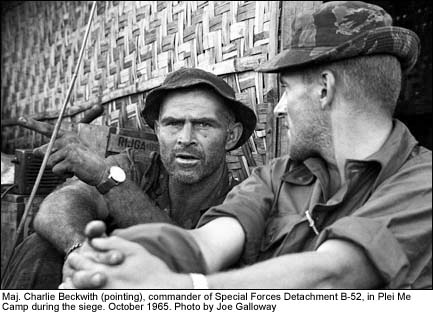

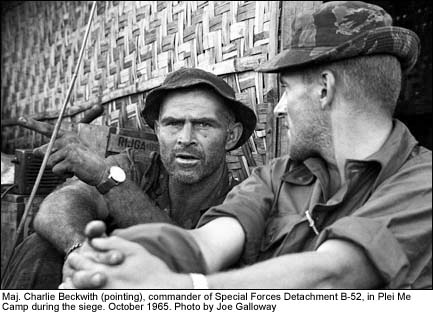

In

mid-October the word passed that trouble was brewing up in Pleiku Province.

The Special Forces Camp at Plei Me had come under siege. We headed that

way in a hurry. By the time we arrived the airspace over the camp had

been shut down. The enemy, this time a regiment of North Vietnamese

Army regulars, had ringed the camp with Chinese-made 12.7mm antiaircraft

machine guns and they had shot down two Air Force fighter-bombers and

one Army Huey helicopter. The Army dispatched a team of Special Forces

B-52 Detachment fighters commanded by Maj. Charlie Beckwith to land

a mile or two outside the camp and infiltrate to stiffen the resistance.

A few reporters and photographers, and one very unlucky UPI television

camera stringer, had gone in with Beckwith. On the final dash into Plei

Me Camp the UPITN stringer raised up to shoot some film and was shot

through the head by an enemy machine gun round. He had literally been

killed before he shot a foot of film. If he had gotten a story UPITN

would have paid him $100. UPI, in its inimitable cheap fashion, later

refused to accept any responsibility for paying to send his body back

to the U.S. for burial.

I had missed that jump and was furiously stalking up and down the flight

line at Camp Holloway outside Pleiku. Who should suddenly appear but

Capt. Ray Burns of Ganado, Texas. He like many of the pilots of the

119th Aviation Company at Holloway was a Texas Aggie. A homeboy. I had

played poker and drunk copius quantities of Jim Beam with them all.

Ray inquired as to my distress. I explained that I wanted to get into

Plei Me Camp and couldn't find a ride. He said hang on; went and checked

the clipboard at Flight Ops. Came back and told me what I already knew:

the airspace was closed. Then he grinned and said he would like to see

the place himself and if I wanted a ride he would take me. Just like

that.

I have a photo I snapped from the helicopter door. The camp, a triangular

shaped affair carved out of the red dirt of the Highlands, fills that

doorway, puffs of smoke from impacting mortar rounds visible in several

places. Ray dropped the Huey in rather precipitously to avoid the machine

guns. I bailed out, the camp defenders flung some wounded aboard, and

Ray was gone, shooting me the bird through the plexiglass. A sergeant

ran up and said, "I don't know who you are, Sir, but Maj. Beckwith wants

to see you right now." I inquired as to which one was the good major.

"He is that big guy over there jumping up and down on his hat," the

sergeant replied. In short order I was standing before a man who would

become a legend in Special Operations Warfare as the founder of the

Delta Forces anti-terrorist teams. The dialogue went something like

this: Him: Who the hell are you? Me: A reporter, Sir. Him: I need everything

in the goddam world; I need reinforcements; I need medical evacuation

helicopters; I need ammunition; I need food; I would love a bottle of

Jim Beam whiskey and some cigars. And what has the Army in its wisdom

sent me? A reporter. Well, son, I got news for you. I have no vacancy

for a reporter but I do have one for a corner machine gunner---and YOU

ARE IT! Me: Yes, Sir.

Beckwith took me to a sandbagged corner of a trench and gave me a short

lesson in the care and loading and firing of the .30 caliber air-cooled

machine gun which sat there, dark, ugly and menacing. He showed me how

to unjam it in case of need. How to arm it. His instructions then were

simple and direct: You can shoot the little brown men outside the wire;

they are the enemy. You may not shoot the little brown men inside the

wire; they are mine. For the next two or three days and nights I lived

in that corner of the trench, beside the gun. What sleep there was was

caught in lulls during the day. One day the Air Force finally managed

to air-drop supplies in the right place; in fact right on top of the

right place. Huge pallets of crates of ammo and c-rations drifted right

down onto the camp, demolishing at least one tin-roofed building and

smashing other defensive emplacements. I reached out and grabbed a Newsweek

reporter, Bill Cook, and yanked him into my trench right before he was

about to be squished by a descending pallet. The snaps of the parachutes

billowing all over the camp were pretty good, even if I say so myself.

Finally a South Vietnamese armored column arrived to the rescue. Bob

Poos of AP and another old friend, Jack Laurence of CBS, were riding

atop the Armored Personnel Carriers. I waved at Poos and asked him where

the hell he had been. He gave me the one-finger salute. The North Vietnamese

had left by then and the hills were silent for the first time in a week.

The air stank with that never-to-be-forgotten smell of rotting human

flesh. The hills were ripped apart by the airstrikes brought down on

the machine gunners, a stark, shattered landscape. We spent one more

night in the camp. Poos was assigned to my machine gun. The next morning

the sky filled with helicopters, U.S. Army helicopters, as a battalion

of the 1st Air Cav arrived to sweep those hills. I went to Maj. Beckwith

to say my goodbyes. He allowed as how I had "done good" as a machine

gunners and he thanked me for the help. Then he said: You have no weapon.

I said that, despite the use he had made of me these last days, I was

still technically speaking a non-combatant. He had a sergeant bring

an M-16 rifle and a sack full of loaded magazines. Beckwith said: "Ain't

no such thing in these mountains, boy. Take the rifle." I took it, slung

it over my back, and marched out to hook up with the Cav on their sweep

through the hills. There we found more than a shattered landscape. We

found shattered machine guns---some of them with the remains of their

gunners still chained to the weapons they manned. But the North Vietnamese

had gone as suddenly as they had arrived. Only the dead remained.

Read

the next page of Joe Galloway's article.

Send

an email message to Joe Galloway

|

We

covered every Marine operation in I Corps, including a combat amphibious

assault landing on the Batangan Peninsula to clear the way for establishment

of a Marine airbase at Chu Lai.

We

covered every Marine operation in I Corps, including a combat amphibious

assault landing on the Batangan Peninsula to clear the way for establishment

of a Marine airbase at Chu Lai.