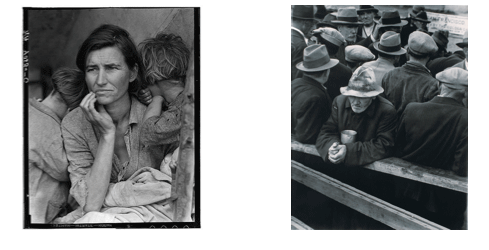

"Migrant Mother is the most famous of Dorothea Lange's photographs, as well as one of the most well-known from the time of the Great Depression between the 1920s and 1940s."

http://artsedge.kennedy-center.org/content/2191/2191_migrantworkers_teachernotes.pdf

"FSA Director Roy Styker considered her most famous portrait, Migrant Mother, Nipomo, California (1936), to be the iconic representation of the agency’s agenda."

http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/661786/Migrant-Mother-Nipomo-California

Two of 87,400 Google results for: Dorothea Lange "Migrant Mother"

"And, of course, Sotheby's once again broke the record for a 20th-century photograph at auction, this time with a Depression-era image of a breadline. Dorothea Lange's White Angel Breadline, a dignified image of men crowding for food, sold for $822,400…."

http://www.artnet.com/magazineus/news/artmarketwatch/artmarketwatch10-14-05.asp

References to the "Great Depression" of the 1930s shadow us now as we face another great financial crisis. But what do we really know of that difficult time, before the ken of most now living? Statistics may defy our imagination but photography of the period conveys some of the harsh realities that many lived.

A government agency created the file of photography, masterminded by economist turned government official, Roy Stryker, which stands as the visual record of 1930s' America. Many have seen the best-known image from the tens of thousands in that file, "Migrant Mother" (1936) by Dorothea Lange. Others with special interests know a lot more of Lange's photography. Lange was one of about a dozen photographers that worked for Stryker at the agency best known as the Farm Security Administration (FSA) including Walker Evans, Russell Lee, and Ben Shahn, who, like Lange, have earned a place in the history of photography. But knowledge of how she worked and the scope of her accomplishment have been greatly enhanced by Anne Whiston Spirn's research published in Daring to Look. Here is a book of great value to anyone interested in documentary photography or how hard life has been in truly difficult times.

The greatest flaw of much photographic reporting is its presentation with limited context and scope. There is an undeniable power to the iconic, such as "Migrant Mother," but understanding is developed with extended and nuanced information. This was the burden of Lange's photographic effort, time in the field observing, discovering and recording resulting in presentations with multiple images and extended text. Spirn's accomplishment is to contextualize and present Lange's documentary work as she did herself, little of which has otherwise reached a public.

In the first of its three main parts, "Dorothea Lange and the Art of Discovery," Daring to Look is a detailed study of how Lange's career developed and played out. It uses an impressive array of primary sources as well as the familiar references and is must reading for anyone interested in Lange. It clarifies her problematic relationship with Stryker, details the progress of her photography, and gives rich insight into Lange's thoughts about her work. "I believe the camera is a powerful tool for communication and…a valuable tool for social research which has not been developed to its capacity," she wrote in her application for a Guggenheim Fellowship, which she won in 1941. That underlying belief was developed as she moved from her portrait studio to photographing the results of economic disaster as seen in the streets around her in San Francisco in 1933. A print of a now-famous photograph from that year, "White Angel Breadline," sold in 2005 for $822,400. The next year she made her first field trip photographing farm laborers with economist Paul Taylor, whom she later married. By 1935 she was photographing for the federal government's New Deal, her work informed by her relationship with one of the country's important social scientists.

Secondly, Spirn concentrates on Lange's 1939 production, editing from Lange's 3,000-plus photographs and including all 75 (1 to 76; there was no 40) of her general captions. Each general caption refers to a related group of photographs that in most cases are listed by number. They vary in length from one paragraph to several and in style from terse facts to commentary to poetry. Many are enriched by quotes from their subjects as well as information from interviews. A good deal of specific financial information is given. These general captions with the multiple photographs they inform make it clear that Lange was documenting social information, not looking for images to be icons or art.

1939 saw Lange with two large projects, following along U.S. Highway 99, which went from Mexico to Canada through California, Oregon, and Washington, and in the Piedmont region of North Carolina, where she worked with sociologists to add photography as a fieldwork tool to their projects. In North Carolina she documented both black and white families involved in tobacco production during July. In August, she went back to following U.S. 99, this time heading up through the Pacific Northwest, writing her last general caption in October. In November Stryker wrote her, "…I am particularly pleased with the general captions….I think this idea of General Captions is the best [that] has come out for some time. The photographic material is enhanced no end when so much good information is available." This shortly after he had fired her.

Dorothea Lange and Paul Taylor, 1939 (© Imogen Cunningham)

1939 was also the year An American Exodus was published, a landmark in the history of photographic books. Lange and Taylor had produced a remarkable study of displaced rural families with innovative text-photo interactions. Her friend, Ansel Adams, with whom she later did several photographic projects, had agreed to make prints for the book, but Lange could not get Stryker, her boss in Washington, to release the negatives. She finally went to D.C. to supervise the printing herself at the FSA lab with Stryker doing his best to get her out of there.

Arguments over control of her negatives were a recurring theme in Lange's time with the FSA. It could be months, if ever, before she saw what she had shot and thus could write captions. And the final prints the lab produced were dismal, she thought. It was undoubtedly difficult for both Stryker and Lange to work separated by the great distance between the East and West Coasts. But Spirn points to the fundamental differences in their intentions as the critical issue. Stryker wanted photographs he could distribute to media and provide as illustrations to a government staff producing reports and exhibits. Lange was thinking herself of final presentations. Their interaction was the classic clash between media producers hiring illustrators for work to use as they wish and serious photographers who have their own vision for their work. Lange was fired from the FSA for the third and last time in 1939.

The impact of Lange's photography comes not just from its combination of visual and emotional appeal, but also from the social information we see and understand from our knowledge of the times. But Lange also hoped to inform us more specifically. It is in the details of her captions that we learn how desperate some of her subjects were, how hard they worked, how little they earned. An example from a picture caption:

August 21, 1939. near Grants Pass, Josephine County Oregon. Hop picker with her children, goes from paymaster's window to the company-owned store, adjoining. She had earned 42 cents that morning. She spent it for 1 lb. bologna sausage, 1 package "Sensation" cigarettes, 1 "Mother's Cake."

In "Then and Now," part three of Daring to Look, Spirn reports with photography and text what she found visiting places Lange had photographed back in 1939. Photographs of the past have often motivated such projects to see and understand how things have changed, or not, and what can better be understood by the comparisons. Here, they add significantly to our appreciation of Lange and of the consequences of great economic hardship as well as federal efforts to ameliorate it. However, it is the insights into Lange's work in Part II that are the primary reward of this book. When we look at "Migrant Mother" or "White Angel Bread Line" we need to remember that these photographs were each the best take of a sequence of shots, that they were made as the result of a belief in the power of multiple pictures with text, including the words of the subjects, and that they were made during years of hard work by an unassuming photographer who recorded for us and the future harder times than we ever hope to see again.

To learn more about Anne Whiston Spirn's book, "Daring to Look," visit the following Web sites:

• http://www.daringtolook.com

• NPR's "All Things Considered" interview: http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=92656801

• NPR's "Think Out Loud" – Memories of the Depression:

http://action.publicbroadcasting.net/opb/posts/list/1542209.page

© J.B. Colson

J. B. Colson studied under the direction of Clarence White for his BFA in photography. After serving as a Signal Corps photographer in Panama he studied documentary film at UCLA. He made non-theatrical films in the Detroit area before teaching photojournalism at the University of Texas, where he inaugurated a program at the Bachelors, Masters, and Ph.D. levels. In the 1980s he worked in Mexico with Jean Meyer and the Collegio de Michoacan documenting village life in the High Meseta. He still teaches a graduate course in the history and criticism of photography. He wrote the introduction to a UT Press book on FSA photographer Russell Lee, published in Spring 2007.