Arriving back in Kabul, a lot has visibly changed since my previous visit in March 2008. A number of Westerners and a lot more Afghans had been killed or kidnapped. In July last summer there was a huge suicide bombing at the Indian Embassy that killed about 50 people. Blast walls had been erected and the bombing changed the mood in Kabul permanently. Afghanistan would appear to be the most dangerous place in the world if the standards weren't already set in Iraq and Somalia. I arrived in Kabul less than two weeks before the August 20 vote and the stakes were incredibly high. America's position on the elections was quite ambiguous when compared to the obvious support of Hamid Karzai in 2004. With the change in leadership in Washington, American policy in Afghanistan seemed to be wandering. President Karzai was reaching out to Russia, China and India while Western powers wanted him to stay focused on defeating the Taliban and curtailing corruption and the related narcotics trade.

© Derek Henry Flood

Female supporters rally at Kabul's sports stadium for opposition candidate Dr. Abdullah Abdullah on Aug. 17, 2009, days before Afghanistan's second presidential election.

This election was a chance at genuine democracy for all Afghans – to break from the past and pave a new way forward – save for those living in districts where it was not deemed safe enough to vote. Deciding where to begin, I dropped by the office of Karzai's principal challenger, Dr. Abdullah Abdullah, which conveniently was within walking distance of my hotel. I'd met Abdullah in a makeshift garrison town near the border with Tajikistan in 2001 when he was the spokesman for the embattled United Front (often called the Northern Alliance at the time) as they confronted the Taliban and its allied foreign militants. Abdullah had entered the relatively brief Afghan presidential election to oppose Karzai's ineptitude and challenge his dubious warlord alignment. But most importantly for the visiting journalist, Abdullah's campaign was accessible compared to the aloof Karzai in his palace amid Kabul’s fortified Green Zone. In the last week of campaigning before the vote, Abdullah ferried aides, parliamentarians and reporters around in an ancient Soviet-era helicopter to provinces all over the country. It was a brilliant bit of logistical PR. Landing in remote villages in a hulking aircraft was practically a made-to-order photo op. Huge crowds of central Afghanistan's isolated Shiite population greeted Abdullah with cheers and the ritual slaughtering of a cow in his honor. He promised them that if elected he would finally bring them much needed development and they celebrated him if only for that shining moment.

The morning before the election I was, for once, intending to eat a not-so-rushed breakfast when it was announced on Sky News via Reuters that two rockets had just been fired into President Karzai's palace compound, possibly striking the palace itself. In contrast to Abdullah's accessibility, when I arrived at the palace gate a palace guard asked me, with a straight face, if I "had an appointment."

© Derek Henry Flood

Independent candidate Ramazan Bashardost campaigns in Kabul's main bazaar after a poll was released listing him as the third-place challenger in Afghanistan's Aug. 20 presidential election. Aug. 14, 2009.

"I'm sorry. Breaking news does not make appointments," I replied in jest. The fact that the alleged damage to Karzai's lair was off-limits to the press was indicative of his campaign throughout. Nothing was to subvert the election, nor the President's reelection. Not even the Taliban making hit-and-run attacks inside Kabul. The polar opposite of Hamid Karzai was the wildly charismatic candidate Ramazan Bashardost. The ethnic Hazara, Paris-educated Bashardost was living and campaigning out of a tent near the Afghan parliament. His efforts had been boosted earlier that day when a poll by a group called the International Republican Institute stated that he had supplanted former World Banker Ashraf Ghani Ahmadzai as the third-place contender. As an aide from another campaign described him to me, "He is not talking to the press, he is shouting!" With less than a week to go before the polls I showed up at Mr. Bashardost's electioneering encampment. The candidate was on the move and a man identifying himself as Bashardost's brother instructed us to jump back into our cars and follow on his guerilla meet-and-greet in the old city's bazaar. With neither bodyguards nor an entourage or even the de rigueur SUV, Ramazan Bashardost walked among the people. Defiantly crossing ethnic and sectarian divides and describing himself to reporters as one of the only Karzai challengers with a clean conscience, Bashardost became a media darling if only for one 24-hour news cycle. Most importantly for this reporter, he was happily accessible.

© Derek Henry Flood

Laborers unload ballot boxes to be counted by Afghanistan's Independent Election Commission from trucks at a warehouse on the outskirts of Kabul.

On the last day of official campaigning, Abdullah Abdullah again invited foreign journalists to a raucous rally. Instead of careening to a far-off corner of the country, his last stop was at Ghazi Stadium in the heart of the capital. Thousands of mostly teenage boys from his Tajik constituency thronged under a blistering sun to the sports complex once infamous for Taliban executions. Abdullah addressed the crowd as the heir to the late Ahmad Shah Massoud [assassinated national hero], and his eyes began to well up with tears. It seemed to hit him at that moment that he had arrived at his place in history among the pantheon of the Afghan Tajik nation's heroes. It didn't seem that Abdullah had envisaged himself in the political spotlight but he was managing the hand he was dealt fairly gracefully.

© Derek Henry Flood

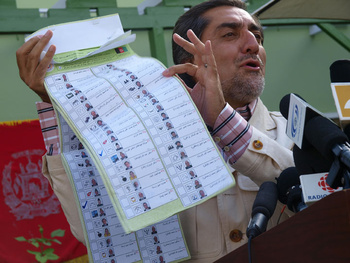

Following Afghanistan's tense elections candidate Dr. Abdullah Abdullah presents evidence of ballot stuffing from false ballots sent to him by a contact in southern Afghanistan where Abdullah is alleging massive fraud by incumbent President Hamid Karzai, Aug. 25, 2009.

A couple of suicide bombings in the preceding days had given cause for Kabulis and internationals to expect the worst. Like the Pakistani elections I covered in 2008, I feared for the worst but hoped for the best. Small numbers of Taliban operatives had easily managed to penetrate the capital's security ring and had threatened voters and election workers with amputations and death to throw off the country's second popular presidential decision. The day of the polling I tried to visit the widest cross-section of voters possible by sect, ethnicity and gender. Crisscrossing Kabul, I met and photographed everyone, from dignitaries to refugees, to try and understand how Afghans from all corners of the country viewed the democratic process. It was put to me by one opposition campaign insider that while Afghanistan is quite a heterogeneous nation, its distinct communities vote very homogeneously, often according to the writ of their own ethno-nationalist leaders. While there were a fair number of militant attacks throughout the country, Kabul was spared the worst and only suffered one major incident and the "terrorists were quickly liquidated" in the words of the country's intelligence director, Amrullah Saleh. I sped across town to the Karte Nau neighborhood looking to photograph a gunfight and found only a desolate polling place with a few brave voters trickling back in to cast their ballots.

Once the polls had closed in the late afternoon of August 20, the stage was set for the next round of drama. Many of Kabul's visiting journalists left at the weekend due to either budget constraints or waning interest in the story and as a pure freelancer I was an odd man out among the remaining bureau and wire reporters. The story continued with allegations of widespread fraud and talk of a runoff election. While President Hamid Karzai was busy meeting with Richard Holbrooke, special U.S. representative to Afghanistan and Pakistan, and carrying on with business as relatively usual, Dr. Abdullah and Mr. Bashardost vociferously reached out to the Kabul press corps with well-orchestrated press conferences and photo ops in much the same manner with which they had presented their campaigns. Though five more years of the status quo with Hamid Karzai seems to be the most likely outcome, no one in the international community nor the most well-connected local elites knows just how this contested narrative of Afghanistan's "big men" will play out.