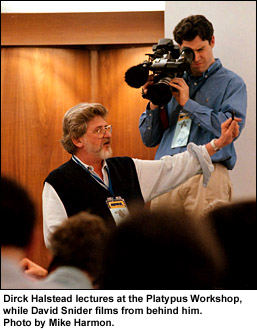

”Forget photo-essays for magazines,” he admonished. “When I first worked at TIME Magazine, twenty-six years ago, I spent over six weeks on an assignment--resulting in not less than six pages of color, and most of them wanted 10 to 12 pages. Now I get six hours to shoot an assignment,” from which maybe one picture gets international play. A few days later, LIFE Magazine proved Dirck’s point by rolling over and breathing its last. During the '90s Halstead decided to seek a new avenue to a future in photojournalism. He decided to learn about video production after realizing: “I’ve been privileged to be so many places, but I’ve been throwing away half..." of his storytelling potential. The bad news is that he found out that “television is a place of fear,” and that broadcast, like print, only has room for a finite amount of content. Now, the good news according to Halstead: shrinking news budgets will also create new opportunities for hybrid journalists who can tell television stories without large and expensive crews. Enter the "Platypus," a term Dirck coined to describe the photojournalist who can tell a story with either stills or video. Like the uniquely evolved egg-laying mammal with the duckbill, the Platypus will adapt to a changing environment. “A lot of people do think I’m crazy,” admits Halstead, "but we’re talking about empowerment. The ability to tell your stories, by yourself.” More than a TV cameraperson, and different from “TV News: The Adventures of a Reporter,” the Platypus is the producer and writer of his or her assignment, shooting with a small digital video camera and editing on home computer. Last year, Halstead created the Platypus Workshop to teach still photographers how to tell stories using new media. The workshop coincided with the annual National Press Photographers Association TV News Video Workshop for television professionals. Dirck held a second workshop in 1999 in Cupertino, California, for magazine photographers. With associates Rolf Behrens, David Snider, Dick Swanson, and Cynthia Vignetti, Father Platypus offered another workshop last month for newspaper and magazine photographers and photo editors, college photojournalism teachers, and description-defying freelancers. On March 11, 2000, twenty-nine still photographers from around the world made their way to Norman, Oklahoma, for the third Platypus video boot camp. They came to learn new technology and different aesthetics in sessions that lasted all day, most evenings, and sometimes all night. Hans-Jurgen Burkhard would be the envy of many aspiring photojournalist. A German, residing mostly in Russia, his assignments for STERN take him around the world. But he says these days his photos receive less play in this changing world. Encouraged by colleague David Turnley, a graduate of the 1999 Platypus Workshop, Hans was determined to enroll in the course so he could make better use of his small digital video camera on his international assignments. “If you’re in there already,” he reasoned, “why not do a film?” Convinced that Platypus training would teach him the basics in two weeks, he caught an airlift out of a besieged Chechnya so he would not miss the workshop. “Otherwise, I will have to wait till next year, and that is too late,” he explained an hour after his arrival in Norman. Arnold Miller of the CAPE COD TIMES was equally determined. “I fought my way here across the beaches of Cape Cod,” he deadpanned. His newspaper is at the brink of the “convergence of the platforms,” which is tech talk for digital transmission of information and entertainment to the public via the Internet. People will dial-up the newspaper, the television, and movies on their home computer. In addition to text and stills, newspapers will offer video on their websites and affiliated cable channels. His down-the-cape neighbor Robert Scott Button has similar plans for the Community Newspaper group.

Rick Kozak had a scare while working for the WASHINGTON TIMES Magazine, Insight. “I met that bean counter in the elevator one day.” His staff job soon went the way of the open expense account. Now a freelancer, he sees tremendous potential in new media. With his new skills and a great connection to America Online--where his wife Cathaleen Curtiss is the director of photography--his future, which may have looked bleak last year, is now promising. Photojournalist Tyagan Miller, based at Indiana University, has an opportunity to tell “parts of the story that aren’t told in stills,” with a documentary project he’s been photographing for four years. When the grant sponsors suggested video, he decided to enroll in the Platypus Workshop, with encouragement from last year’s graduate David Turnley. With each new Platypus assignment Tyagan was heard mumbling, “there’s so much to remember...this is so complex!!…” as he synthesized information about interview technique, audio edits, screen direction, jump cuts, transitions, pacing, sequencing, white balance, and other intricacies of video journalism. Participants in the Platypus six-day video workshop worked in groups of three. Each team had one leader who was signed up to shoot and edit. Most agreed it was the biggest attack on the ego they’ve ever endured. Already accomplished in their fields (40 was their average age), they had to learn a new set of skills in a very short time. “You will tell yourself, I can’t do this, this is not for me,” warned Halstead. “Every day the bar’s gonna be raised…. But you will graduate from this workshop as a professional television novice,” he guaranteed. Day One of the workshop, I did the “Warm Up.” Since the Platypus is now required to produce his/her own story, I told producer jokes before Dirck announced the first assignment....

Assignment #1 was an exercise called Vox Pops. Each team was required to go to a shopping mall to shoot interviews known in TV newsrooms as “MOS, or Man on the Street” or “VOX POPS, Voice of the People.” The shooters found that while the principles of lighting and composition are the same as in still photography, they could no longer be the fly-on-the-wall waiting to capture the decisive moment. They had to present themselves to their subjects, and ask them questions. Subjects who might shy away from a still photographer welcome the same photographer equipped with video. “People love to be on camera,” explained Halstead, “It’s part of the culture.” The workshop students were convinced of this truth as they shot their Vox Pops exercise at the Sooner Mall in Norman. Shoppers readily answered questions from the philosophical, “what does God look like?” to the topical “how are gas prices affecting you?” As the tapes were critiqued, the Platypus teams learned the importance of asking the right kind of questions to generate interesting and useable responses. Workshop assignments were shot with the Canon XL-1 digital video (DV) camera. The medium sized three-chip camera has the “best bang for the buck,” according to workshop instructor Rolf Behrens. A veteran news photographer, editor, and producer for SKY-TV in Africa, Behrens switched from his betacam, the 25-pound industry standard, to the DV camera after injuring his back a few years ago. He has since shot several TV programs with the XL-1, including an entire two-part Nightline special for ABC News with Platypus David Snider, and contributed to two other Nightline pieces, including one in February about the buffalo in Yellowstone. The Canon XL-1, with its interchangeable lenses and dedicated XLR (professional 3-pin) audio inputs, makes good clean pictures and sound. The controls are user-friendly and are fairly intuitive for those trained in either stills or video. Nevertheless, it was a lot to think about, and a challenge for the shooters. Day Two I warmed up the workshop by introducing

them to an arcane bit of TV terminology: the lumper.

Then the shoot/edit participants, still struggling with mastering the camera, were asked to shoot “B-Roll,” the footage that makes up 80% of most television stories. A holdover term from the days of newsfilm, B-Roll refers to most footage other than a person talking on camera. Next, "Rolf’s Routines" were handed out and drilled by Mr. Behrens. ANTICIPATE, FOCUS, FRAME, SHOOT, HOLD. FIND A NEW SHOT. “ONE SHOT IS NEVER ENOUGH” and perhaps the most difficult caveat for a frame-by-frame practitioner: " EVERY SHOT MUST HAVE A BEGINNING, A MIDDLE, AND AN END.” To illustrate the importance of these routines, Behrens described the first riot footage he shot in South Africa at the start of his TV career. Although he thought he had shot everything important, the tape editor who screened Rolf’s video fast-forwarded his footage, popped the tape, and threw it out the window. The shots were not useable because they were not held long enough. After he let that disturbing experience sink in, Rolf screened an example of a successful shoot from another riot, after he had learned his lesson. This time the video told the story. His shots were held long enough, he rolled for audio “whilst” taking cover, and his footage included a beginning, middle, and an end. The Platypus teams were asked to shoot five minutes of B-Roll footage, concentrating on making sequences, series of wide shots, close-ups, and reverse angles of the same action. Close-ups of the face are especially important in television. The team footage was screened and critiqued by workshop faculty. I was struck by the beautiful natural lighting in most of the footage. But the faces weren’t there. The close-ups weren’t there. The shots weren’t long enough. And even some of the compositions were terrible. Shooters had trouble knowing whether the camera was rolling, and several teams brought back footage shot while they thought the camera was turned off. Worse, nobody’s shots advanced their story. In fact, there was no story, no sequence, no context, just a collection of still shots on video. “Slide show,” I commented. After they were flogged for their mistakes, the teams were invited to learn for themselves why these close-up and reaction shots were so necessary. They were asked to edit their B-Roll footage for the next lesson. Final Cut Pro is the edit software that is rapidly becoming an industry standard for independent TV and filmmakers. Similar to the pricey ($20K- $30K) non-linear systems by Avid and Media 100, Final Cut Pro, an Apple program, costs about $1,000, according to the Platypus faculty.

All editing in The Platypus 2K Workshop was done on the non-linear computer program. Non-linear editing means that the video and audio do not have to be selected and recorded on tape in sequence. Unlike linear, where an analog video tape is played back on one machine and recorded on another--similar to dubbing music onto an audio cassette--non-linear edits can be made and re-made in any order. The edits store digital information but they don’t actually record and re-record. Therefore the signal quality is never degraded, and the edits don’t have to be made in sequential order the way they do on a linear system. A “fire wire,” or high-speed serial digital input cable, allows the direct transfer of field tapes into the computer without any loss of signal. The digital video and audio are edited in the computer, and can be re-edited in any order without losing signal quality. Video and audio can be moved around or trimmed, and most results can be viewed instantly. The program has keyboard commands, but it also works as a point click system, intuitive for most people who know how to use a computer. When the edit is complete, the information is “dumped” back to tape. The digital edit information can be stored on a Zip disk, for easy re-access. You don’t need the eye-hand coordination of a TV technical director to edit non-linear. You do, however, need the aesthetics of a television storyteller, and that was part of the next Platypus assignment. Each workshop team edited their B-Roll tapes into a one-minute video. Eric Miller, freelance photojournalist and picture editor for Reuters in Minneapolis, said the challenge of learning Final Cut Pro was “an experience from hell. It’s like having to prepare a color photo for press the first time in Photoshop, under deadline pressure, and with sound.” After, though, he marveled, “It’s a great program, it’s deep.” This, as his team attacked the next assignment-- to shoot ten minutes of video and edit a 2-minute piece on Final Cut Pro. “It’s an interesting challenge,” agreed Pauline Lubens, of the SAN JOSE MERCURY NEWS. “Right now it’s a frustrating new challenge.” Arnold Miller, of the CAPE COD TIMES, was beginning to get it. Working at Red Team’s edit bay with John Stewart, he built a video sequence they had shot at Flanagan’s Costume Shop in Norman. Concentrating on his edit mantra, their story started to come together: “Click it, drag and drop, Insert...THIS IS SO COOL!!!” The workshop got a real boost that evening during a teleconference with Tom Bettag, executive producer of Nightline, who revealed his interest in Platypus journalism. JB Russell, who lives in Paris, was very encouraged. He hopes to expand some of his European photo-essays into television programs, and asked whether he needs a specific American tie-in to European news. “One of the great lies is that America is not interested in foreign news,” Bettag replied. “The truth is: accountants aren’t interested in foreign news.” In fact, said Bettag, “The U.S. is starved for foreign news.” Peter Turnley, whose small Sony video camera looks well-worn, agrees. He shot his half hour Nightline special incorporating stills and video from Bosnia almost immediately after completing the Platypus Workshop one year ago. Driven by the need to tell more after he took a NEWSWEEK Magazine cover photo, he took the DV camera that hangs on his shoulder, and told more of the story on video. It was about a refugee, despairing and hyperventilating after losing his wife and two small children who were presumed dead. Peter used video to expand on the emotion and information of his still photographs. With their new Platypus package, he and Amy return to Paris with more of these opportunities. “Anybody can do this provided they have the motivation,” Dirck Halstead continued, encouraging his students. The rewards are great. Emerging Platypi used their video exercises to tell stories about characters in small town America.

The journalist who got a great laugh from this footage is David Bergman. Staff photographer on the MIAMI HERALD. David has a great feel for people, and an affinity for audio and video. “I’m intrigued by motion and sound” said Bergman whose team turned out video essays about a body-piercer, a young man in search of love in the stockyards, and a little drama about a still photographer who decides to change his career. How tough was the Platypus Workshop? For some, like Steve Elfers, chief photographer of the Army Times Publishing Company, the assignments were challenging, but he was able to make steady progress. His final assignment, about a couple who frequent a '50s drive-in, was worthy of any TV magazine show.

John Hall, photo editor at the FORT LAUDERDALE SUN-SENTINEL, attended the workshop to find out what kind of training his still photographers will need when they are asked to shoot video. Hall likened the preparation he received in the lecture portion of the workshop to getting ready to ride a bull. “You’re in the chute, your feet are down, you wrap your hand, you adjust your hat. You’re ready, you nod…and you’re out of the chute flying around spinning till you’re thrown right off!” But after several very rough rides, Hall was able to deliver a complete one-minute assignment that not only looked beautiful, but told a story. “How often have you heard applause for

one of your pictures?” asked Rolf Behrens. By the end of the Platypus Workshop,

everybody was capable of making a video that inspired an ovation.

|

“Photojournalism

is D.E.D., Dead,” Dirck Halstead told twenty-nine still photographers in

Norman, Oklahoma. “Get over it, it’s not coming back.”

“Photojournalism

is D.E.D., Dead,” Dirck Halstead told twenty-nine still photographers in

Norman, Oklahoma. “Get over it, it’s not coming back.”

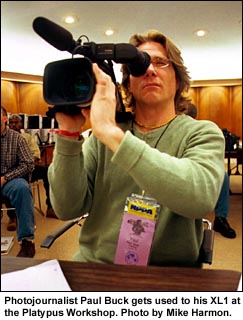

Paul

Buck, freelance photographer from Dallas, invested his own time and money

on the workshop. “I want to learn now with others like me. It’s taught

by professionals who know what they’re doing, and know what we’re capable

of doing.” He thinks the commercial potential for video is there for some

of his assignments. “I want to be there before it’s too late.”

Paul

Buck, freelance photographer from Dallas, invested his own time and money

on the workshop. “I want to learn now with others like me. It’s taught

by professionals who know what they’re doing, and know what we’re capable

of doing.” He thinks the commercial potential for video is there for some

of his assignments. “I want to be there before it’s too late.”

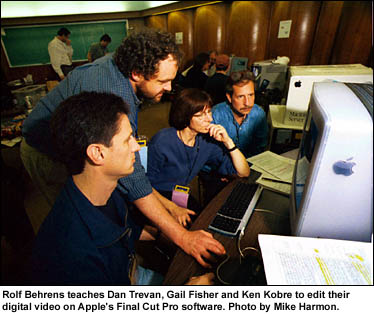

Rolf

Behrens and editor Dick Swanson, a convert to video following a tremendous

career at LIFE Magazine, teach and preach Fundamentals of Editing using

the Final Cut Pro system on the Apple G4 computer. The five edit bays at

the Platypus Workshop also included a Sony V-10 player, to input the video

material to the computer and an external TV monitor. The package is easy

to put together: Amy Roth Turnley and her husband Peter Turnley, who are

producing a TV documentary in France, decided to buy an edit package in

Oklahoma where they were enrolled in the NPPA Advanced Storytelling Workshop.

They found everything they needed at Comp USA, and were set up ready to

edit with Rolf’s help, in a few hours.

Rolf

Behrens and editor Dick Swanson, a convert to video following a tremendous

career at LIFE Magazine, teach and preach Fundamentals of Editing using

the Final Cut Pro system on the Apple G4 computer. The five edit bays at

the Platypus Workshop also included a Sony V-10 player, to input the video

material to the computer and an external TV monitor. The package is easy

to put together: Amy Roth Turnley and her husband Peter Turnley, who are

producing a TV documentary in France, decided to buy an edit package in

Oklahoma where they were enrolled in the NPPA Advanced Storytelling Workshop.

They found everything they needed at Comp USA, and were set up ready to

edit with Rolf’s help, in a few hours.

Chip,

a character from a shoot, makes the ultimate onion burger. Pointing

out that although the fat from the burger will probably clog your veins,

the extra stress on the heart is good for your health. “It’s like

taking your heart for a jog.”

Chip,

a character from a shoot, makes the ultimate onion burger. Pointing

out that although the fat from the burger will probably clog your veins,

the extra stress on the heart is good for your health. “It’s like

taking your heart for a jog.”

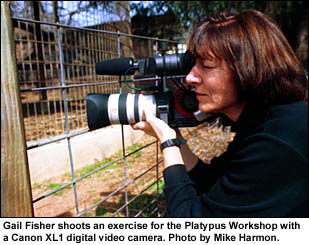

For

others, like Gail Fisher of the Los Angeles Times, picking up “another

dimension that I’m missing,” seemed like an uphill battle. Following each

of her critiques I wondered whether Gail was ever going to give us a close-up

shot. Towards the end of the workshop, she pulled it all together for her

final assignment. Gail and her team worked tirelessly to create a beautiful

and heartfelt piece about an unusual performer.

For

others, like Gail Fisher of the Los Angeles Times, picking up “another

dimension that I’m missing,” seemed like an uphill battle. Following each

of her critiques I wondered whether Gail was ever going to give us a close-up

shot. Towards the end of the workshop, she pulled it all together for her

final assignment. Gail and her team worked tirelessly to create a beautiful

and heartfelt piece about an unusual performer.