Lest We Forget by Roger Richards

Sometimes it's easy to forget how privileged we are to be photojournalists. We get to go places and photograph people that the majority of individuals never get access to. We often see and experience things from behind the scenes of great events. Sometimes we feel truly blessed. Then there is the flip side. As a staffer with a daily newspaper in a major city, I am assigned to cover a great many press conferences and photo ops--staged performances where politicians and people famous for being famous send out a call via their publicists, knowing that even if the subject of the "news" conference is cheesy and banal, there will always be some news organization on hand to cover it. After shooting enough of these events, even the most motivated photojournalist begins to question his choice of profession. I deal with it by getting revenge on the people who stage the ops. That is, if I come to the conclusion that the press is being too blatantly manipulated. Take for instance a press conference that a bunch of Washington politicians recently called at a school to announce some new education initiative that had little merit and stood less than a snowball's chance in hell of passing into law. These shameless hucksters had attracted a good showing of members of the national press, it being a very slow news day. The poor school kids were the wallpaper in the background as the gathered windbags blathered on for the cameras. I waited until well into the program to make my move. Every frame I squeezed off was like therapy. I left the school a happy man. I had gotten the safe shot of them talking and something else, too. The photo my paper used on the metro section's front page the next day was of a very important U.S. senator in the foreground with a large group of kids behind her. The schoolchildren were simultaneously yawning, sleeping, nose-mining, squabbling and making faces. Kids-1 Pols-0 . Despite all the B.S. we have to shoot, I remain committed to my profession. There is nothing else like it if done with passion, skill and artistry. We are, by virtue of our profession, able to influence people's lives. This is a very grave responsibility, one that some in our profession take too lightly or do not recognize at all. When people allow you into their lives, it means that you owe your subject the respect of at least trying to see things from their point of view, even if you do not agree with or like them. To do one's best for good and not for self-promotion and self-aggrandizement. I recently returned from an assignment in a Central American country. I had been there a couple of times in the 1980s when vicious civil wars were convulsing the region. The quality of life of the poorest people had not changed for the better, especially after a series of natural disasters. My reporter colleague and I were visiting a temporary camp for displaced persons, where people lived in abysmal conditions. One of our guides took my hand and led me to a tiny concrete room with a metal roof. Inside, an old woman, who looked to be no more than a skeleton, sat on a ragged mat on the floor, clutching a wicked-looking knife. She looked as though she was going to use the knife on herself. A man stepped in and spoke to her softly, coaxing the knife away. She began to weep. I asked what was happening with her and was told that she was in the last stages of tuberculosis and would probably be dead very soon. The woman picked up a bible in which there were several photos of a young woman and a very young child. The woman told me it was her daughter, and that she was now five years old and in an orphanage. I was stunned. How could this old woman be the mother of a five-year-old? I was informed that she was only 28. I picked up my Leica and asked the woman if I could photograph her, and she nodded. Then she began to weep again. I made my photographs and left. I was able to justify to myself for making those photographs of that suffering woman because I felt that maybe, just maybe, those images of her would spur someone into action, someone who could help ease the pain of others who are suffering like her. In my view, there can be no other reason for making photos of someone in those dire straits. The line between voyeurism and journalism is very thin in such circumstances. Since coming back I have shown the images

to a few of my colleagues. Some of the comments, like "great stuff," were

grating, although I knew that no harm was meant. I still feel almost guilty

for making these photos. The dying woman granted me the privilege of recording

her terrible circumstances. It is only because I know the reason I made

them in the first place that my conscience has remained clear.

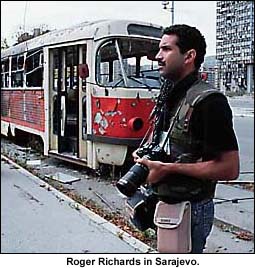

Roger Richards is a staff photojournalist at the Washington Times in Washington, D.C. He is the editor and publisher of the multimedia website Digitalfilmmaker.Net. |