|

Returning to Saigon,

March 2000

© 2000 David Burnett

Contact Press Images

|

|

Click on the

photo to see an enlarged image.

In March of this year, I returned to Vietnam for a 12 day stay for Fortune

Magazine. It was the first time in five years that I had passed

through Customs at Tan Son Nhut, and was surprised how in those five years

even passing through customs had become, like much of Saigon,

so modernized. I lived in Saigon from 1970 to 1972 working as a free

lancer for Time and Life (then a weekly; then existing, for

that matter). My trips back in '94 and '95 were more focused, more

rushed (9 days, and 2 days respectively), and now I had almost two weeks

to see the city again, to feel it, listen to its cacophony (even when I

didn't particularly want to), and smell its smells. Each day started

with crackly, overly volumed tapes screeching across the waterfront as

hundreds of older Vietnamese would begin their morning ritual exercises

at 5:30 am. I was drawn there nearly every morning to watch the sunrise,

and was never disappointed.

In March of this year, I returned to Vietnam for a 12 day stay for Fortune

Magazine. It was the first time in five years that I had passed

through Customs at Tan Son Nhut, and was surprised how in those five years

even passing through customs had become, like much of Saigon,

so modernized. I lived in Saigon from 1970 to 1972 working as a free

lancer for Time and Life (then a weekly; then existing, for

that matter). My trips back in '94 and '95 were more focused, more

rushed (9 days, and 2 days respectively), and now I had almost two weeks

to see the city again, to feel it, listen to its cacophony (even when I

didn't particularly want to), and smell its smells. Each day started

with crackly, overly volumed tapes screeching across the waterfront as

hundreds of older Vietnamese would begin their morning ritual exercises

at 5:30 am. I was drawn there nearly every morning to watch the sunrise,

and was never disappointed.

And

at that early hour, the friendliness of the Vietnamese people started,

and didn't subside throughout the day. Smiling greetings everywhere,

visual games that had no words, and the kind of contact that you relish

having everyday at home. Living in Washington, and often visiting

the Vietnam Memorial, I’m well aware of the pain that still follows many

of the American vets and their families when the subject is the War.

What is amazing in Vietnam is to see just how they have societally decided

to move on from the War. Half the country is less than 25, true,

but half the country is well over 25. And that no doubt creates problems.

More than once I was reminded by an elder of the difficulty of actually

trying to make the younger generation understand the struggles Vietnam

suffered through during the war. But despite the museums, despite

the studies in school, despite all the family memories, one has the impression

that the children are already living in a truly post war world. And

at that early hour, the friendliness of the Vietnamese people started,

and didn't subside throughout the day. Smiling greetings everywhere,

visual games that had no words, and the kind of contact that you relish

having everyday at home. Living in Washington, and often visiting

the Vietnam Memorial, I’m well aware of the pain that still follows many

of the American vets and their families when the subject is the War.

What is amazing in Vietnam is to see just how they have societally decided

to move on from the War. Half the country is less than 25, true,

but half the country is well over 25. And that no doubt creates problems.

More than once I was reminded by an elder of the difficulty of actually

trying to make the younger generation understand the struggles Vietnam

suffered through during the war. But despite the museums, despite

the studies in school, despite all the family memories, one has the impression

that the children are already living in a truly post war world.

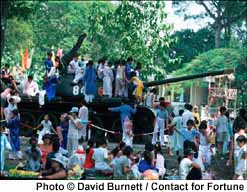

On

my first Sunday I stumbled into an enormous gathering of grade school children

on the grounds of Unification Palace (Thieu's Presidential Palace), where

thousands of kids were playing group games, snacking (something that seems

to be a national sport), and generally running and yelling a lot.

Grouped by their classes, I also saw parents, often dressed very nattily

in J Crew style threads, looking over some kind of standardized test, and

their skeptical reactions seemed to say, ‘‘of course my kid got it

right, the teacher must be wrong!’’. I couldn’t understand what they

were saying to each other, but it reminded me of the little yuppie parental

gaggles that form in front of schools in the States before the kids

are released. It was jarring for me to see the hundreds of kids climbing

on the memorialized tanks and fighter planes which had heralded in the

new regime twenty five years ago. To the kids, the tank was just

another jungle gym toy in the park. On

my first Sunday I stumbled into an enormous gathering of grade school children

on the grounds of Unification Palace (Thieu's Presidential Palace), where

thousands of kids were playing group games, snacking (something that seems

to be a national sport), and generally running and yelling a lot.

Grouped by their classes, I also saw parents, often dressed very nattily

in J Crew style threads, looking over some kind of standardized test, and

their skeptical reactions seemed to say, ‘‘of course my kid got it

right, the teacher must be wrong!’’. I couldn’t understand what they

were saying to each other, but it reminded me of the little yuppie parental

gaggles that form in front of schools in the States before the kids

are released. It was jarring for me to see the hundreds of kids climbing

on the memorialized tanks and fighter planes which had heralded in the

new regime twenty five years ago. To the kids, the tank was just

another jungle gym toy in the park.

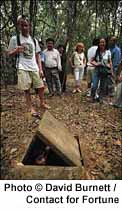

My

last day, I took a car out to Cu Chi to see the famous tunnels where, amazingly

, thousands of Viet Cong troops lived, moved and attacked from. The

tunnels have become a big tourist attraction for both Vietnamese and foreigners.

After the trip to Cu Chi, I had the driver head up the road about 15 km

to a village called Trang Bang. Approaching the village, I

kept trying to find little hints of the place that would remind me of just

where I'd been when I was last there. It was in this little town

in the summer of 1972 that VN Air Force Skyraiders accidentally dropped

napalm on a group of villagers who had taken refuge together from the fighting.

It was in this group that Pham Thi Kim Phuc and her family had been when

the bombs hit. She ran with her brother out of the brush onto the

paved road, and towards us, her skin terribly burned from the heat.

The few journalists there had hung just outside the village, waiting to

see what would happen, and I remember Nick Ut sprinting off from where

we were standing the moment he understood just what had happened.

He was followed moments later by Alex Shimkin, a Washington Post

stringer who died in an ambush a few months later, while I, changing

film in an old Leica, stayed there a few extra seconds trying to load my

camera. I then ran down the road and shot some pictures, and later

returned to Saigon. I had been working for the New York Times

that day, and ended up at AP to have my film processed. It's

seldom when you are at an event that you truly know a special picture has

been made. And at Trang Bang that day none of us did. But when

Nick walked out of the darkroom with a dripping wet 5 x7 print, Horst Faas,

who had temporally returned to Saigon to help run the AP picture operation,

looked at the first image of Kim Phuc, and said sardonically, "Nick Ut,

you do good work today." It was that simple. We knew it was a damn good

photograph, but sometimes you have to wait for the world to respond to

know how a picture has touched people. I sent my negs to LIFE

that night, having wired a picture to the Times, and included a note to

New York to "check with AP for an original print, because one of their

guys, Nick Ut, took a very good shot." Indeed. My

last day, I took a car out to Cu Chi to see the famous tunnels where, amazingly

, thousands of Viet Cong troops lived, moved and attacked from. The

tunnels have become a big tourist attraction for both Vietnamese and foreigners.

After the trip to Cu Chi, I had the driver head up the road about 15 km

to a village called Trang Bang. Approaching the village, I

kept trying to find little hints of the place that would remind me of just

where I'd been when I was last there. It was in this little town

in the summer of 1972 that VN Air Force Skyraiders accidentally dropped

napalm on a group of villagers who had taken refuge together from the fighting.

It was in this group that Pham Thi Kim Phuc and her family had been when

the bombs hit. She ran with her brother out of the brush onto the

paved road, and towards us, her skin terribly burned from the heat.

The few journalists there had hung just outside the village, waiting to

see what would happen, and I remember Nick Ut sprinting off from where

we were standing the moment he understood just what had happened.

He was followed moments later by Alex Shimkin, a Washington Post

stringer who died in an ambush a few months later, while I, changing

film in an old Leica, stayed there a few extra seconds trying to load my

camera. I then ran down the road and shot some pictures, and later

returned to Saigon. I had been working for the New York Times

that day, and ended up at AP to have my film processed. It's

seldom when you are at an event that you truly know a special picture has

been made. And at Trang Bang that day none of us did. But when

Nick walked out of the darkroom with a dripping wet 5 x7 print, Horst Faas,

who had temporally returned to Saigon to help run the AP picture operation,

looked at the first image of Kim Phuc, and said sardonically, "Nick Ut,

you do good work today." It was that simple. We knew it was a damn good

photograph, but sometimes you have to wait for the world to respond to

know how a picture has touched people. I sent my negs to LIFE

that night, having wired a picture to the Times, and included a note to

New York to "check with AP for an original print, because one of their

guys, Nick Ut, took a very good shot." Indeed.

Now in 2000, trying to find that piece

of road in what is now the prospering and peaceful town of Trang Bang was

not easy. I had not brought my contact sheets with me, and had to

drive up and down the road a few times, until I approached a bridge and

turned, seeing the roof of the pagoda through the trees. That is

what I remembered, and it was still there. We stopped, and I got

out and walked around for while. Just outside the town, the only

sounds were slowly building revs of the motor bikes which were headed my

way. That, and the laughter of the school girls in white ao dais

pedaling their bikes home from school. No signs that I could find.

Nothing to mark the spot. Just a sense of a place which, 28

years later, bears no trace of the calamity. I kept thinking about

that moment in Nick's picture, when the horror is so evident. And

as much as no one under 25 may know anything about the war, no one over

the age of 35 will ever forget that picture. The world changes and

moves in ways that we cannot always imagine, but as a picture will sometimes

remind you, there is a memory we the public share of a certain moment which

will live far beyond its place. |