This is a personal piece, the sort that I generally do not write. It is prompted by the year 2000, which marks two significant milestones in the nation’s history: It’s been 30 years since the May 4 killings on the Kent State University campus, where I was a senior, and 25 years since the ignominious departure of Americans and Vietnamese from the roof of the American embassy and other buildings April 29, 1975. For me these are not celebratory dates—even the word "anniversary" strikes a false note. "Observances" is the word I prefer—a neutral word for explosive events and emotional memories. The undeclared war in Vietnam shaped my adult consciousness. My passion for photojournalism began with experiencing John Filo’s photograph of a girl kneeling beside the body of Jeffrey Miller, his blood streaming down the pavement beside her. Howard Ruffner’s photographs in LIFE had an impact too. Acquaintances killed at Kent State and in Vietnam, and friends who returned from the war with fused spines, nightmares, and great silences, are emblematic of the deep contradictions of the era. Sitting in a bedroom watching a small television; I clearly remember President Nixon’s announcement that U.S. forces were in Cambodia. The date was April 30, 1970, according to Stanley Karnow in his history of Vietnam at war. My first reaction was, "This is just too much; it will never end." Four days later four Kent students would die and others would be wounded and paralyzed. Now, as I prepare to return to the campus of Kent State and hug friends I haven’t seen for 30 years, I am surprised by my unresolved emotions, though traveling to Vietnam for the first time in my life this year has helped in some small way. I will write a little of that later. ***

Instead I was at home in a front room when I heard screaming and turned to see my neighbor, Maggie [name changed], pounding on my screen. I’d never seen anyone beat their fists against a screen. I ran out thinking one of her small children had been hurt. As I got closer I understood what she was crying: "They’re shooting people on campus. Tom is there." Simultaneously I heard the sirens, louder and louder and louder, piercing the air—wailing down the hill towards campus, towards the just announced "shooting." Maggie was hysterical, and I held on to her. Then I grabbed the phone to call the yearbook office for information. Maggie was saying, "You can’t get through, the phone system has been shut down." I turned on the campus radio station. They were giving out partial, largely incorrect information. But we didn’t know that. Maggie ran out the door to return home a few doors down the street. I stood there with a dead phone. Should I run to campus? Should I stay put, in case MY husband, who was also on campus, found a way to call? I had so much energy surging through me and nothing to focus on but the "shooting" and the seemingly never-ending sirens. Later, while I was pacing back and forth on the sidewalk, another neighbor, Mrs. Miller, came out and slowly walked up to me as if she were in a dream. "They just said students and one guardsman have been shot, and one person’s name is ‘Miller.’" She was clearly worried about her son John who was on campus. We tried to speak casually about how many people were named "Miller" and how we were only getting bits and pieces of news. A little later I looked to my left and saw Maggie frantically mowing her lawn with an old push mower. She was moving so furiously she could have done the block in a matter of minutes. On the right people were hollering and running down the middle of our residential street. One woman, I remember, had her hands to her head—she was running her fingers through her hair and then straight up. It was an incongruous and terrifying sight. Apparently this group of students had run all the way across campus and up the few blocks to our street. We ran out to them. There had been shooting outside Taylor Hall, there was blood. I don’t remember the rest. The students ran on. Maggie and I both heard from our husbands; they were staying on campus, one to work with the administration in an underground room and one to take photographs. The night was filled with helicopters—it seemed like dozens—though perhaps it was only one. A helicopter with loud whirling blades and swirling bright lights passed over the rooftops again and again. A curfew had been announced. Maggie and I had decided earlier that I would spend the evening with her and the children. I would be at home and would violate the curfew to get there. A quiet small town neighborhood was under siege, full of odd lights and deafening sounds, and I was scared. Then I allowed myself to get angry at the preposterous scene. I turned off the lights and planned which tree to run to. I took off, listening to the helicopter circling for another pass. To the tree, the next tree, a bush, inside an old garage, and onto Maggie’s back porch. I remember thinking, "What the hell is going on here? What the hell am I doing?" In the days that followed, rumors abounded: Townspeople had purchased all the axe handles from the hardware store; some parents were keeping their children home from school fearing that the college students were living in the sewers and would come out and kidnap them. The university was closed. Instantly. Thousands of students went home. We left town several times, once seeking refuge at my aunt’s house. While there, an uncle walked in and said in a loud voice (perhaps he imagined I had lost my hearing), "Well, there she is from Kent State. They should have shot MORE of them." We went home. Getting back into town took time. All roads were blocked, and each person had to prove he or she lived in Kent. Sitting on my front steps I watched army vehicles pass by with M-1s (or similar National Guard issue) pointed out the sides directly at the houses, at me. If they suspected somebody of something, they drove up over the lawn to their front door. The anxiety and sadness lasted for months. It still defies description. I was completely hollow, melancholy, as if everyone and everything I had ever cared about were dead. People gathered but didn’t have a lot to say. We watched the Kent State hearings on television. Somebody passed around a joint. "Am I the last person on earth who hasn’t tried this?" I inhaled. Nothing mattered. ***

Flying over Vietnam from Hong Kong I could see the country’s green rice fields, the family burial markers, and the houses, which generated an unexpected swell of anticipation I cannot describe. We arrived at the hotel in Hanoi and met up with the others who had traveled to be at the show’s opening in Hanoi. Hanoi is a city of lakes, French Colonial architecture, ancient temples, and an Old Quarter that sells just about everything. The high humidity makes even cool days seem warm. The combination of landscape and heat leaves room for contemplation as one slows down to meet the pace. Each morning I awoke thinking, "I can’t believe I am finally in Vietnam—and in HANOI." Opening the window I could hear birds singing in the trees and many from cages that hung outside shops. This seemed, perhaps, too idyllic, but it was a wonderful way to start the day. There are people in Hanoi with money, but

on the street one could see that the shop owners often lived with their

extended family in their small market spaces. They managed by selling food,

coffee, baskets, and many other goods. Visitors who had been there before

remarked on the increasing amounts of goods and food for sale and that

the Vietnamese were now able to purchase these things.

The most beautiful historical place I visited was the compound of the Temple of Literature. This was the site of the first university in Vietnam—the first class of Confucian scholars graduated in 1075 AD. In 1442, an emperor began the practice of recording the names of these distinguished scholars on stelae. There are 82 in all, and each stele is carried on the back of a stone turtle. This was a calm and thoughtful landscape with gates signifying Confucian principles, gardens, ponds, and the temple. It signifies for me what Hanoi gave me—great peace. No one who knows me would claim I am generally content or calm, but as I sat in front of one great stone turtle, both great and petty things from my life seemed to fall away. This temple quietly expressed to me what any Vietnamese will tell you: The war is over. Get on with your life. I will go back, perhaps to Hanoi, but also to Hué and Ho Chi Minh City. Now I will remember, it is the choice to make the journey that is important. My journey to Kent State lies ahead. Marianne Fulton

|

On

May 4, 1970, I skipped class. Had I not, I would have been walking through

the parking lot and down the sidewalks where Sandra Scheuer was killed.

I would have been carrying books, as she was, walking to the same class

in the music and speech building.

On

May 4, 1970, I skipped class. Had I not, I would have been walking through

the parking lot and down the sidewalks where Sandra Scheuer was killed.

I would have been carrying books, as she was, walking to the same class

in the music and speech building.

At

this writing I have not returned to Kent State, but I have gone to Vietnam.

In March I was invited with a small group for the exhibition Requiem: Photographs

by Photographers Who Died in Vietnam and Indochina, a version which had

originated in Kentucky. (Please

see the Horst Faas piece in the April TDJ.) This large exhibition was called

The Vietnam Collection, because it had been given to Vietnam. Though this

invitation was the impetus for my trip, I readily accepted for the sheer

experience of being in Vietnam.

At

this writing I have not returned to Kent State, but I have gone to Vietnam.

In March I was invited with a small group for the exhibition Requiem: Photographs

by Photographers Who Died in Vietnam and Indochina, a version which had

originated in Kentucky. (Please

see the Horst Faas piece in the April TDJ.) This large exhibition was called

The Vietnam Collection, because it had been given to Vietnam. Though this

invitation was the impetus for my trip, I readily accepted for the sheer

experience of being in Vietnam.

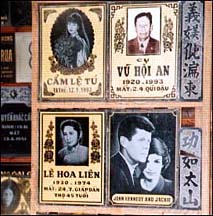

In

the Old Quarter streets are open markets. One street is filled with fabric

and clothing stores, another with shoes. I was struck buy the blocks of

storefronts selling gravestones. Each stone was carved with skill by the

man sitting in front working on his latest job. It appeared that the carvers

had branched out in their craft; not only were they copying photographs

of the deceased on gravestones, but they were also carving memento plaques

of brides, babies, and in one place, a likeness of John and Jackie Kennedy.

In

the Old Quarter streets are open markets. One street is filled with fabric

and clothing stores, another with shoes. I was struck buy the blocks of

storefronts selling gravestones. Each stone was carved with skill by the

man sitting in front working on his latest job. It appeared that the carvers

had branched out in their craft; not only were they copying photographs

of the deceased on gravestones, but they were also carving memento plaques

of brides, babies, and in one place, a likeness of John and Jackie Kennedy.