GOING TO THE WHITE CHURCH WOULD HAVE BEEN EASY

5:30 a.m. came painfully early this morning. Especially after going to bed at 2 a.m. But I knew as I fell asleep that at first the alarm would not make sense to my tired body and brain, especially on my only day off this week, but then the reality of today would shutter me awake. Sure enough, the obnoxious alarm clock

rattled me out of sleep, I lay there wondering why I had to be awake now,

and then I vaulted out of bed, "Today is it, the church comes down. Letís

get ready."

A year ago the story was so different. Hurricane Floyd swept over Eastern- North Carolina a week earlier, leaving Princeville, Pinetops, parts of Tarboro and other towns under as much as eight feet of water. Think about that, look at the ceiling in your house, it is about eight feet, now imagine your house, your neighborsí, and every house in a 50 mile radius under that much water. Now think about what would be usable after the water went down, nothing, absolutely nothing. The water, not clean, filled with mud, hog waste, and raw sewage. Even after the water recedes, all metal rusts, all wood rots, all plastic is contaminated, your life as you know it is gone. "But I am insured," you say. Are you? Your insurance probably only covers falling water---rain coming through the roof, not rising water--- flooding. This is an issue I have grown to know well over the past year, most people in the flooded areas of North Carolina did not have flood insurance, many had no insurance at all. This hurricane did not wipe out million dollar beach houses belonging to people who would just write them off of next yearís tax return, like many Carolina coastal hurricanes do. This force of nature, this act of God, hit one of the most economically depressed areas of the state, people who had worked their entire lives for the few things they had, and now they were gone. A storm with the cruelest outcome possible. And as it seemed, a racist storm. For you see, the people who live in the lowest lying areas around the flooded Tar River of Eastern North Carolina are predominantly African American. Many have farmed or lived on the same plot of land their family has held for generations, some such as Princeville, since their families were released from slavery. Many of these towns still live divided, a white side and a black side, and the floods went after the black sides for some reason no one can understand. October 3, 1999---It was the first Sunday after the water went down to the point people could return to their homes. Not return like go back inside and live again, but return to find everything, and I do mean EVERYTHING destroyed. It looked like a war zone from a third world country, collapsed houses, crushed cars, piles upon piles of rotting house innards. Nothing could be saved that could not be boiled, so other than glass and metal, nothing could be saved. Pictures, clothing, furniture, things people worked an entire life to accumulate were now rubbish in the street. Many people had to flee their homes with only the clothes on their backs and what they could carry. Think about it, what would you take? I came into work that Sunday morning knowing I would be going to Edgecombe County as I had done everyday since the flooding. Our assignment editor informed me I would be doing a story on churches that flooded out and what they were doing to continue with services and support their congregations. Great story, yes, only one problem. It was 11:00 a.m. That is when every church I have ever been to in the South (about 30 in all) start their Sunday morning services. Tarboro is an hour and a half away; I might get there for the last seconds of church, but nothing to make a story out of. I tried to impose the logic of the time-space continuum on our assignment editor, but it was over his head. Fine, there are a thousand stories in Tarboro, I will find one, but donít bank on the church story." He still did not get it as I stomped out of the newsroom. This was my first solo trip to Tarboro.

Until this day, I had a reporter with me to discuss what the people were

going through, what we were going through. I got to Rocky Mount and knew

I was not in the right mindset to go to the devastated area yet. I stopped

at the Texaco on 301 to fill up the car. There were no open gas stations

in Tarboro and very few functioning phone lines, not a place I wanted to

be stranded. I also got some water and

I popped in the tape and realized it was the perfect soundtrack for driving to Tarboro- ---Miles Davis Ascenseur pour Líechafaud. Simple, dirty recordings. It is all the outtakes from the scoring sessions for a 1958 French film. They are slow and sad, technical and deliberate. I felt myself instantly go to the place that I mentally needed to be to face Tarboro. Twenty minutes later I was exiting Highway

64 to Princeville/Tarboro. Trash everywhere, some flooded cars still abandoned

in the median. I drove past the high school that was now an emergency shelter.

The McDonalds was now open at least. I drove through the city square, lined

with big white Victorian homes that remained unharmed by the flood. Then

I headed toward the river. Two city blocks later the destruction began.

Mattresses and computer monitors, easy chairs and childrenís toys, wedding

albums and air

I drove past the big Episcopal church,

sandbags still lined the stone walls. A few people stood in the English

courtyard smiling and shaking hands. They were well dressed and getting

into big shiny cars, they were not flood victims by any means. They would

be easy to talk to about this, but there was not the level of story there

I knew was out there. I then drove the road closest to the river, St. Lukeís,

a historically black Baptist church was

I had missed my story and now I had to

find something else we had not done six times over. It was still early

on Sunday so people were not really cleaning or gutting their homes yet.

The day before when I was with a reporter, we saw some groups set up in

the town hall parking lot giving out free lunches. I drove back to Main

Street, but no one was at the Town Hall. People were cruising up and down

Main in their Sunday church clothes looking at the damage to downtown stores.

That could be my story, but I had seen a

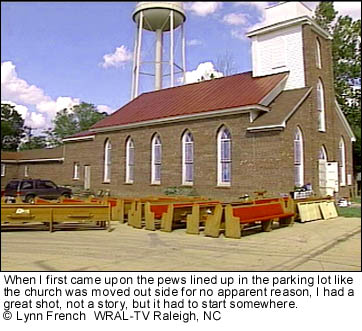

I looped in and out of streets, I hoped I would not get a flat tire from driving through all of the debris from the homes. The piles of possessions were mind boggling, some of them you would look at the house and wonder how did all that stuff fit in there. Then I tried to imagine if I had to throw all of my worldly belongings on my front lawn for the world to look at, what would they think? And then there was the shot, it was not

a story, but what a shot. This story book red brick church with a tall

white steeple sat on the corner in the midst of the destruction with all

the pews lined up in the parking lot like they had decided to move services

outside for no apparent reason. I pulled in the parking lot next to the

rows of benches and walked to the front stoop of the church with just my

camera. Upon closer inspection, this little building was a flood victim.

A pile of rubbish was started along the side of the building, The Bible

sat on its pulpit, waterlogged, with the blue ribbon marker still stuck

in Psalms. I drove about three blocks, everything

around me was still destroyed. I looked for a church, but there was not

one to be found. I drove to where I knew it was too far and turned around.

I drove back down the street almost back to Eastern Star again. One more

try and then we will go back and ask again. I drove up the street and saw

lots of cars parked like there was a church in the area. Then a big white

wooden building caught my eye. It did not look like a church, more like

a really big, old house with peeling paint

Now, I am a white girl raised in New Mexico.

I did not meet a black person until I was in the fourth grade. The only

black people on TV were Sanford & Son and Whatís happening while I

was growing up. Until I went to college, I only knew the stereotypical

things about African American culture like Kwanzaa and Martin Luther King

Jr.ís "I Have a Dream" speech. But before you think too badly of me, I

grew up in a Hispanic culture that North Carolina has yet to grasp. I celebrated

Las Posadas and made Christmas tamales and went to midnight mass in Latin

even though I am not Catholic. I set out

I got my gear and walked up the short steps. I stood in the foyer that was not even the size of my hall closet. I pressed on the tall wooden door and a black woman dressed head to toe in white, even with crisp white gloves poked her head around the door to see what I wanted. I quickly and quietly tried to explain to her that Deacon Parker sent me. She squeezed my elbow and escorted me to a clear area in the back of the church behind everyone, and EVERYONE turned around to see why the white girl with the big camera was there. I could feel my face turn hot and I eeked out an embarrassed smile, no one smiled back. Slowly attention turned back to the front of the church where one of the deacons was talking about donations for flooded families, but the children still hung their chins on the backs of the pews with their big dark eyes fixated upon my every move. I looked over the congregation. Despite the fact many of these folks lost everything they ever owned a week ago, they were dressed for church. Not Dockers and a pressed shirt or a floral print blouse with a pleated skirt kind of dressed for church, oh no, women in glorious hats with feathers and shiny beads, jewelry at every point on the body where clothing ended and flesh began, fancy dresses trimmed in vibrant colors and work hewn hands covered in snow white gloves. The men in their dark three-piece suits with bright bow ties and felt hats hanging off their knees tapped their spit shined shoes on the hollow floor. I knew the second Reverend William Clayton

stepped to the pulpit. Every face turned to shine on him. He was not going

to take it easy on the parish despite these hard times. "MY EYES DO NOT

KNOW TEARSÖ BECAUSE I KNOW I AM NOT IN THIS ÖBY MYSELF!" My ears rang from

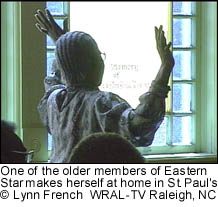

his voice bouncing across the ancient church walls. Women raised their

bare palms to the sky and men thumped their heels with the Reverendís cadence. I stood there in the back of the church, exhausted but enlightened as to what brings people to church. Slowly older members of the church approached me about my presence in their Sunday service. I put my best defense first, "I just met Deacon Parker at your church up the street, he told me I would not want to miss this, I wanted to see that you all are okay." One by one a crowd built around me as people welcomed me to their borrowed church and asked how I liked it. I told them I would be back. December 26, 1999---Thank God this day

fell on a Sunday. I knew a month ahead of time where I would be on the

day after Christmas. No post Noel shopping stories for me this year, I

was going to my church. I could barely sleep Christmas night, I was so

excited to be living up to my promise to the people of Eastern Star. I

gave myself a two hour head start to Tarboro, enjoying the lack of traffic

on Highway 64 and listening to Miles Davis the

As I observed the congregation settling in, I knew I would never be able to go back to boring white churches again. It was so obvious how much these people got out Sunday mornings. It was not the aloof filing in of families to soft organ music I knew, there were loud ladies hugging in the aisles and old men grabbing onto one another as they doubled over with laughter as children climbed on the pews and played on the pulpit. Eventually everyone settled into their seats as the choir churned on the stage. I knew what my story was, the two churches under one roof living in harmony. I rolled on the music and the people and the pastor. Yes, he was wonderful, completely different from Reverend Clayton, he jumped up and down on the stage and wore a long black robe. But he had the same effect on the crowd, again people rose to their feet, clapping and cheering, almost like a football game between Good and Evil, but you knew here that Good had the home field advantage. The service was coming to an end as I finally spotted two familiar faces in the crowd. Then the pastor called on one of them to rise and give some good news about Eastern Star to the congregation. A tiny woman you would want to be your grandmother, in her petite Sunday suit and matching plaid pillbox hat with pink flowers stood and announced that Christmas morning Reverend William Clayton and his wife brought a baby girl into the world. I had only met the man once, but I felt a rush of happiness push through my chest. The pastor dismissed the congregation and I rushed to catch the small woman. She remembered me from a few months earlier and gladly agreed to an interview. As I stood there asking Miss Shirley Mayes about the newborn member of their little church, her eyes became sad. "How is the rebuilding of the church going?" I piped up. She took a deep breath, "We are going to have to tear the church down". Hot tears suddenly burned in my eyes, this could not be, it was like she told me a good friend was going to die soon. She then told me the engineers determined the wood under the brick was too rotten from the water trapped in the walls to rebuild it. I thanked her as I grabbed a few more quick interviews about the two churches sharing the building for now what would be a very long time. I guess that is the bittersweet beauty of a church, they saw the opportunity to share as a blessing despite the depressing things that brought them together. It was like the first time I saw my best

friend, Lisa, after she was diagnosed with cancer, my head was heavy with

the mourning ahead. I was not sure of the time we had left together, but

I was well aware of the joy and strength in its history. I went to the car to get my camera and

a white Lincoln pulled up. One of the familiar faces from todayís congregation

got out. "I knew you were headed over here," the grandfatherly man said

as he settled his winter hat on his head and patted me on the shoulder.

I told him how sorry I was to hear the church would be torn down. The man,

who had seen many Sunday mornings in this church, gave me a sweet smirk,

" I am an old man, and she is my old girl." Right then I knew there was

no stopping Deacon William Joyner, just start rolling, again, no tripod,

no good microphone. We stood on the sidewalk in front of the church, "She

is sick, itís time for her to go, we will live on, the church lives inside

of us, not in a building. This old woman and I have been together for a

long time but her time is done." I drove back to Raleigh and announced to the newsroom that the church had to be torn down. That night we tagged out the sad story with the good news about Reverend Claytonís newborn daughter. In late February I covered a ground breaking

of a housing complex in Princeville. I was not really excited about watching

politicians shoveling sod, until I saw Reverend Clayton with a spade in

hand. After the ceremony I ran up to the pastor to ask when his building

would be demolished. Five months had passed and I figured he would not

remember me so I walked up and introduced myself. The reverend laughed

heartily, and pushed my hand away and gave me a big hug, "There my wife

and I were on the day after Christmas

In June, I had a Sunday where nothing was

going on in Raleigh or Durham, it was time to check on the church. Reverend

Clayton promised to call me when the church would be torn down, but I know

our phone message system at the station and I feared the building was a

pile of bricks now. It was the right weekend for Eastern Star to hold services,

not St. Paulís. I got there good and early again and set up in what had

become my regular spot. I hugged Deacon Joyner and wished Miss Mayes a

happy birthday. When the Reverend stepped onto the stage he looked at me

and smiled. I could see why people do

Two weeks ago I opened up my work e-mail, TARBORO CHURCH DEMOLITION. I felt my heart sink as I opened up the message, it was finally here. I called the Reverend to let him know I would be there Monday morning. It fell on my only day off that week and I was glad. I could go down there on my terms, leave when I wanted and I did not have to slap it together into a story and could just enjoy the time with the congregation. I let the assignment desk know about the demolition and they told me Brian Bowman, another one-man-band photographer/reporter would be there. I was glad they saw how important this was to me. 5:30 a.m. came early. It took a moment

for me to figure out why I was getting up this early on a Monday morning

(my weekend). But then I could not get ready for my day fast enough. I

loaded up my gear and headed to Tarboro. I did not even wait for the radio

signals from Raleigh to get weak before I popped in Miles Davis. As I exited

64 into the town, the last year flashed before me. The people of this area

have come so far in the last year. There are parts of town where you have

to look for a minute to find evidence of

No one was really sad, they had a long

good bye and it made this seem merciful that it was finally here. It would

take about a week to tear the church down since the structure was so complex.

There was the leaning wall and the steeple that was not part of the original

church and all of the additions onto the back.

The color of a church. I thank God for

the lessons I have learned about doing the easy story versus doing the

good story.

Lynn French

|

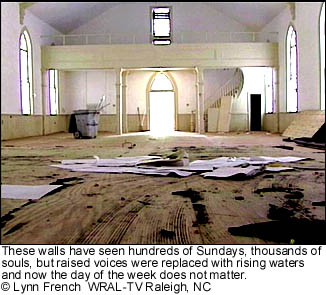

Stacks

of Hymnals blew in the breeze, no longer inspiring song, but rather emitting

the odor of wet dog. The organ sat in a puddle, the wood veneer already

starting to warp from wetness and heat. I slowly opened the front doors

of the church preparing myself for the worst, like there would be dead

bodies inside or something. The high white sanctuary opened up before me,

in the corner under one of the purple stained glass windows was a solitary

man pulling at the sopping red carpet. "Hello" I tried not to startle him

too much. He turned around and flashed me a huge genuine smile, "Why Hello!

What can I do for you?" The glistening black man in a sweat soaked t-shirt

and jeans made squishing sounds as he walked over the wet carpet toward

me. I introduced myself and told him I was checking on

Stacks

of Hymnals blew in the breeze, no longer inspiring song, but rather emitting

the odor of wet dog. The organ sat in a puddle, the wood veneer already

starting to warp from wetness and heat. I slowly opened the front doors

of the church preparing myself for the worst, like there would be dead

bodies inside or something. The high white sanctuary opened up before me,

in the corner under one of the purple stained glass windows was a solitary

man pulling at the sopping red carpet. "Hello" I tried not to startle him

too much. He turned around and flashed me a huge genuine smile, "Why Hello!

What can I do for you?" The glistening black man in a sweat soaked t-shirt

and jeans made squishing sounds as he walked over the wet carpet toward

me. I introduced myself and told him I was checking on

An

"Amen" or "Speak it Brother" sprung out of the audience from time to time.

My heart raced in my chest at the excitement around me, old men were now

on their feet clapping their hands to the time of the reverendís words

and women swayed in their seats with their faces turned up to God and their

eyes closed to the harsh realities around them. The reverend whipped off

his jacket and wiped sweat from his brow as his voice boomed over the worked

up crowd as their clapping came together into a single rhythm of pressed

palms and then the choir broke out into a boisterous hymn that the entire

church sang along with despite the fact the organ drowned and the sheet

music washed away.

An

"Amen" or "Speak it Brother" sprung out of the audience from time to time.

My heart raced in my chest at the excitement around me, old men were now

on their feet clapping their hands to the time of the reverendís words

and women swayed in their seats with their faces turned up to God and their

eyes closed to the harsh realities around them. The reverend whipped off

his jacket and wiped sweat from his brow as his voice boomed over the worked

up crowd as their clapping came together into a single rhythm of pressed

palms and then the choir broke out into a boisterous hymn that the entire

church sang along with despite the fact the organ drowned and the sheet

music washed away.

I

drove down the street that brought me to St. Paulís three months earlier.

I could see the steeple that someday would not be there. I pulled into

what was now my parking space next to the little red brick church. I did

not even get the camera out, I just walked in to the church. I looked at

the giant stained glass windows, "They will have to save those and put

them in the new church", I thought as I heard my own hollow steps on the

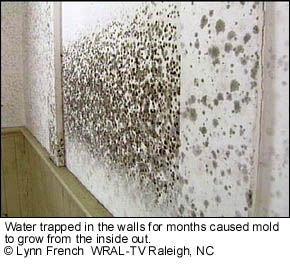

bare floor. I looked at the south wall, where the water would have first

come in, there was still the line of demarcation between clean and dirty.

Mold spores the size of pocket change and as varied in color

I

drove down the street that brought me to St. Paulís three months earlier.

I could see the steeple that someday would not be there. I pulled into

what was now my parking space next to the little red brick church. I did

not even get the camera out, I just walked in to the church. I looked at

the giant stained glass windows, "They will have to save those and put

them in the new church", I thought as I heard my own hollow steps on the

bare floor. I looked at the south wall, where the water would have first

come in, there was still the line of demarcation between clean and dirty.

Mold spores the size of pocket change and as varied in color

We

walked inside the church and the deacon pointed out structural problems

the church has had for almost a hundred years, the east wall leans outward

toward the top. We looked inside some holes punched in the walls, he showed

me the ailing wood structure. The red bricks on the outside are a veneer

over the wooden church Eastern Star was founded in. The original church

was Howard Presbyterian, a white church built up the road a few miles during

the Civil War. In 1906, the building was sold to the people who wanted

to break away from St. Paulís and start Eastern Star. The structure was

rolled on logs and pulled by mules to its present site.

We

walked inside the church and the deacon pointed out structural problems

the church has had for almost a hundred years, the east wall leans outward

toward the top. We looked inside some holes punched in the walls, he showed

me the ailing wood structure. The red bricks on the outside are a veneer

over the wooden church Eastern Star was founded in. The original church

was Howard Presbyterian, a white church built up the road a few miles during

the Civil War. In 1906, the building was sold to the people who wanted

to break away from St. Paulís and start Eastern Star. The structure was

rolled on logs and pulled by mules to its present site.

I

was shooting an interview for Brian with Deacon Joyner when we heard the

bulldozer tear into the roof. I looked as a solitary member standing down

by the tree at the edge of the parking lot burst into tears. Reverend Claytonís

wife handed their baby daughter to another member of the church and ran

to the lady and hugged her. The men stood there, stoic for a moment and

the reality of this hit them like the brick wall falling to the ground.

As the first truck full of church pieces pulled away and the front end

loader took a moment of silence, Deacon Parker ran to the construction

site and grabbed an armload of bricks, "These are for our older members,

so they can remember what color she was".

I

was shooting an interview for Brian with Deacon Joyner when we heard the

bulldozer tear into the roof. I looked as a solitary member standing down

by the tree at the edge of the parking lot burst into tears. Reverend Claytonís

wife handed their baby daughter to another member of the church and ran

to the lady and hugged her. The men stood there, stoic for a moment and

the reality of this hit them like the brick wall falling to the ground.

As the first truck full of church pieces pulled away and the front end

loader took a moment of silence, Deacon Parker ran to the construction

site and grabbed an armload of bricks, "These are for our older members,

so they can remember what color she was".