For Richard Drew the worst moment photographing the tragedy of the

was not photographing the burning buildings, or people throwing themselves

out of the windows to certain death, or the collapse of the buildings,

nor any of the other gruesome sights that he saw that first day. His

worst moment came when he decided to turn his attention on other parts

of the story and moved up to the Armory where the families of the

missing people were trying to locate their lost loved ones:

“It was sort of early in the morning, and there were not a lot

of people there. I went around the corner to get a cup of coffee to

come back around to this pen area where all the people were coming

over to tell their stories to the media, and I was on my way back

with this cup of coffee, and my phone rang. It was my 3-year-old daughter,

and my wife said "I want to tell you something", and she

hands the phone to my daughter, and she says "Daddy, I just want

to tell you that I love you" and I guess that really got to me,

because I realized there are lots of people out there who are not

going to hear their 3 -year-olds say " Daddy, I love you."

anymore. It was really tough. I had to take 2 days off after that.

The reason it really hit me, I think, is because I had been reading

a newspaper on my way to that site that day, and I think the headline

was "10,000 Dead." I think it was the Daily News article.

That's the first time I think I really realized, I just didn't see

a building fall down with airplanes hitting it, or whatever happened,

I watched 10,000 people die, possibly, in the collapse of those two

buildings. I can't remember anyone ever seeing 10,000 people die at

one time. It was really hard for me.”

Drew certainly isn’t a newcomer to the tougher moments of this

country’s history. At the very beginning of his career he was

one of only four photographers in the kitchen of the Los Angeles hotel

when Bobby Kennedy was shot and killed. His day on September 11th

started on one of history’s softer moments covering a maternity

fashion show in Bryant Park for the Associated Press, his employer

for the last 31 years. He got there before the show started to get

some shots of the pregnant models in hair and makeup, and was about

to go and stake out his “real estate” in front of the runway

when a CNN camera operator heard over his headphones from the control

room that there had been an explosion at the World Trade Center. Rumors

of such an event had been common since the car bombing in 1993, and

Drew paid it little heed until the CNN cameraman told him that a plane

had crashed into one of the towers. At the same time Drew’s office

called him on his cell phone with the same report. Needless to say,

the pregnant models were left behind as he boarded an express subway

train to Chambers Street, the stop just before the Twin Towers. Upon

his arrival at the scene he did not immediately notice that by this

time both towers were on fire. Instead he mingled with the crowd,

deliberately not wearing his press pass, while he concentrated on

photographing the debris on the ground from the impact and explosion

of the planes, and stunned people, many of who had been cut by flying

glass.

At one point he was moved on by a policeman and told that he had to

go over to West Street. This didn’t bother him at all, because

it would give him a better angle, and also because that was the location

of the ambulances and a triage unit where Drew expected the many injured

would be brought initially.

“Usually I find that the ambulance people and the rescue people

don't really care if you're there. They are not in the enforcement

angle of this; they are there in the rescue part of this. So, I hung

with them, waiting for people to come, and I was standing next to

a very nice policeman from the 13th precinct, and all of a sudden

he said "Oh my gosh, look at that!" I looked up and there

were people coming out of the building. Falling or jumping from the

building. There was a woman there from the rescue squad, and she started

pointing them out to me too, and we must have seen six or eight or

maybe more people and I was photographing them as they were coming

down. It was quite something to see. We were watching one guy, who

is in one of my photographs that has been published a lot, some guy

was actually clinging to the outside of the building, outside on the

girders. He had a white shirt on. We were watching him for the longest

time while all these other people were falling, and I alternated between

that and this other stuff, then there was the huge rumbling sound.

I had my 80-200 lens on, and this rubble just starts to fall down.

I had no idea it was the building falling. I thought maybe it was

part of the roof or the façade.”

As the first building imploded he managed to get about eight frames

before being pulled by one of the rescue workers away from the location

and up Vesey Street:

“It was really tough to see. Tough to work, because you couldn't

breathe. I managed to get to an ambulance, and I managed to get a

surgical mask, and I wore that for a long time, but it was getting

in my eyes, it was hard to see. So I went over to the spot where they

were moving all the ambulances to, which was the spot where I was,

about a block and a half from the original location, and I was photographing

people then walking out, covered with ash and all the ones you have

seen like that, when a ranking police officer in a white shirt came

running up the street, yelling "we all have to get out of here!"

So, I’m thinking they are just trying to clear the area, and

I moved to the center median strip, where there were some bushes,

and I tried to hide myself in the bushes, so all the hoopla would

go past me. I had changed lenses to sort of a medium telephoto lens

and thought if they are going to kick me out, I am going to make some

more pictures of this building on fire, then leave. As I picked my

camera up to do this, the top of the second tower poofed out, and

I held my finger on the trigger, and made nine frames of this building

cascading down, the North Tower, then the camera stopped shooting,

because it takes nine frames then stops. Then I said "I've got

to get out of here!" and I ran a block and a half north to Stuyvesant

High School.” The photographs that Drew took of the people leaping

from the burning buildings have been widely published and widely criticized.

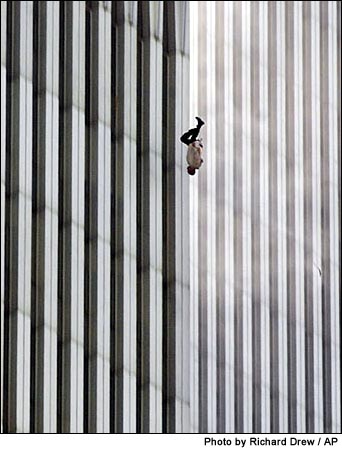

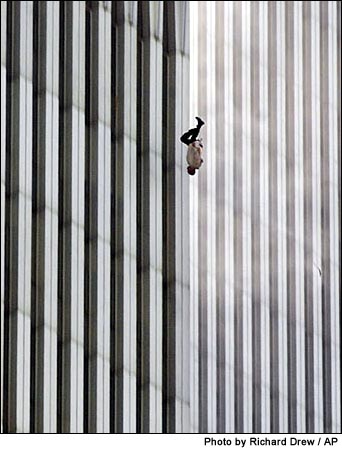

“The

one image that’s been causing a lot of discussion is one image

that I shot of a man falling head-first from the building, before

the buildings fell down. He was trapped in the fire, and decided to

jump and take his own life, rather than being burned. I don't know.

I have no idea and that has caused a lot of controversy among readers

of newspapers that used the picture. There are two newspapers that

have had their ombudsman write stories about the picture, explaining

why they used the photograph. The Memphis Commercial Appeal and the

Fort Worth Star Telegram. They received a lot of complaints, and that

is only two I know about that were complaining about the picture.

Our readers e-mailed and phoned, and complained that they didn't want

to see this over their morning corn flakes. This was a very important

part of the story. It wasn't just a building falling down, there were

people involved in this. This is how it affected people's lives at

that time, and I think that is why it’s an important picture.

I didn't capture this person's death. I captured part of his life.

This is what he decided to do, and I think I preserved that. A reporter

from the Toronto Globe and Mail thinks he has traced down the family

of this guy, and some people in his family don't want to believe that

it is him. Other people, according to the article say it is him. Others

won't even look at the picture in his family, and they are still handling

their own grief about it, but that is what I like to say, I didn't

capture his death, I captured part of his life. That has been very

important to me.”

“The

one image that’s been causing a lot of discussion is one image

that I shot of a man falling head-first from the building, before

the buildings fell down. He was trapped in the fire, and decided to

jump and take his own life, rather than being burned. I don't know.

I have no idea and that has caused a lot of controversy among readers

of newspapers that used the picture. There are two newspapers that

have had their ombudsman write stories about the picture, explaining

why they used the photograph. The Memphis Commercial Appeal and the

Fort Worth Star Telegram. They received a lot of complaints, and that

is only two I know about that were complaining about the picture.

Our readers e-mailed and phoned, and complained that they didn't want

to see this over their morning corn flakes. This was a very important

part of the story. It wasn't just a building falling down, there were

people involved in this. This is how it affected people's lives at

that time, and I think that is why it’s an important picture.

I didn't capture this person's death. I captured part of his life.

This is what he decided to do, and I think I preserved that. A reporter

from the Toronto Globe and Mail thinks he has traced down the family

of this guy, and some people in his family don't want to believe that

it is him. Other people, according to the article say it is him. Others

won't even look at the picture in his family, and they are still handling

their own grief about it, but that is what I like to say, I didn't

capture his death, I captured part of his life. That has been very

important to me.”

If it’s disturbing to look at these pictures over your morning

cornflakes, it’s traumatic to take them, and witness the terrible

events of September 11th. For himself Drew has found solace in talking

about the sights that he has seen with his colleagues, and even in

interviews such as the one with the Digital Journalist. His sense

of professionalism also gives him a stoical attitude:

“It's part of the history that I have been able to photograph

in my lifetime for the AP, whether it be a car wreck, or a fashion

show, or this thing. I just have to place in that file drawer where

you say, "I have covered major stuff", and this will go

in that major file drawer. I just go on and do my thing. I have covered

the stock market 3 or 4 days or more since this has happened and whatever

else has to be done, that's what I will do.”

However this philosophical attitude does not extend to his children.

He worries about the America that they will grow up in, especially

his youngest daughter:

“My 3 year old, whenever she sees a tall building, says "Daddy,

is that the World Trade Center?" All this has permeated her psyche.

I told her the other day: "You won't see the World Trade Center

anymore. There was an explosion and it fell down." There is no

way she can grasp the enormity of 10,000 people being killed, or 6,000

people being killed, at one time at her age. It will change how she

grows up in the United States, because certain freedoms that I have

enjoyed over the years are going to be different. Things are going

to change. Personal freedoms. How we move around. How we are looked

at. People in Europe have been doing this for years. We all travel

through airports in our lives. I think the first time my wife and

I got off a plane in Madrid before we went through customs, to see

soldiers carrying rifles in the airport, it was something we didn't

see here. I always thought security was a joke at New York airports,

and in US airports to begin with. You can go through any European

or Middle Eastern airport and things are a lot tougher.”

However he also feels that the heightened security that is omnipresent

in New York post-September 11th will at best give New Yorkers the

illusion of greater safety.

“When I go to my office every day, people are checking IDs, bags

and stuff. But I think the toothpaste’s out of the tube on this

one because no one brought anything in in a bag, anything in in a

suitcase, nothing in a backpack. It came in at 600 miles per hour

in a 757 airplane. So I think all this is giving people a false sense

of security in a way by throwing up all these security nets around

major buildings. It's not going to come in that way. We've already

seen how it's going to come in, in a truck, like it did at Oklahoma

City at the Federal building or it's going to come in by plane, like

it did at the World Trade Center. It's going to be major.”

Drew hasn’t seen one image that he considers to be the iconic

summation of the disaster, but he feels that the photographic coverage

of it has influenced the American public:

“I think it has rallied the Americans. At least what I can see.

It’s seemed to have rallied everyone. Everyone is carrying flags,

they have flags on their cars, and they have flags on their lapels,

flags on their hats at the NY stock exchange. They have flags everywhere.

People on the street corners are all selling flags. There is a sense

of patriotism that probably wasn't that strong as it was when this

thing started, you know. You can't screw with us. We are going to

go after you. We're not going to sit back here and take it.”

He pauses and reflects for a moment: “We'll see how effective

that is.”

© 2001 Peter

Howe

“The

one image that’s been causing a lot of discussion is one image

that I shot of a man falling head-first from the building, before

the buildings fell down. He was trapped in the fire, and decided to

jump and take his own life, rather than being burned. I don't know.

I have no idea and that has caused a lot of controversy among readers

of newspapers that used the picture. There are two newspapers that

have had their ombudsman write stories about the picture, explaining

why they used the photograph. The Memphis Commercial Appeal and the

Fort Worth Star Telegram. They received a lot of complaints, and that

is only two I know about that were complaining about the picture.

Our readers e-mailed and phoned, and complained that they didn't want

to see this over their morning corn flakes. This was a very important

part of the story. It wasn't just a building falling down, there were

people involved in this. This is how it affected people's lives at

that time, and I think that is why it’s an important picture.

I didn't capture this person's death. I captured part of his life.

This is what he decided to do, and I think I preserved that. A reporter

from the Toronto Globe and Mail thinks he has traced down the family

of this guy, and some people in his family don't want to believe that

it is him. Other people, according to the article say it is him. Others

won't even look at the picture in his family, and they are still handling

their own grief about it, but that is what I like to say, I didn't

capture his death, I captured part of his life. That has been very

important to me.”

“The

one image that’s been causing a lot of discussion is one image

that I shot of a man falling head-first from the building, before

the buildings fell down. He was trapped in the fire, and decided to

jump and take his own life, rather than being burned. I don't know.

I have no idea and that has caused a lot of controversy among readers

of newspapers that used the picture. There are two newspapers that

have had their ombudsman write stories about the picture, explaining

why they used the photograph. The Memphis Commercial Appeal and the

Fort Worth Star Telegram. They received a lot of complaints, and that

is only two I know about that were complaining about the picture.

Our readers e-mailed and phoned, and complained that they didn't want

to see this over their morning corn flakes. This was a very important

part of the story. It wasn't just a building falling down, there were

people involved in this. This is how it affected people's lives at

that time, and I think that is why it’s an important picture.

I didn't capture this person's death. I captured part of his life.

This is what he decided to do, and I think I preserved that. A reporter

from the Toronto Globe and Mail thinks he has traced down the family

of this guy, and some people in his family don't want to believe that

it is him. Other people, according to the article say it is him. Others

won't even look at the picture in his family, and they are still handling

their own grief about it, but that is what I like to say, I didn't

capture his death, I captured part of his life. That has been very

important to me.”