Newsweek

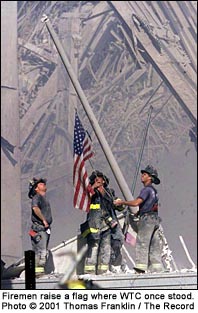

magazine's cover September 24 was the picture of the three firefighters

raising the American flag above the shattered World Trade Center.

The image by Thomas E, Franklin of the Bergen Record (NJ) also appeared

in hundreds of papers worldwide. It garnered immediate attention—three

firefighters working intently, hoisting the flag on tons of shifting

rubble. They are covered with the ashes generated by the explosion.

The composition of the photograph is excellent: Three men evenly spaced

looking at the flag with concern. Their upward gaze, the position

of the flag and the large pole rising to the left-hand side of the

photograph makes it a memorable image.

Newsweek

magazine's cover September 24 was the picture of the three firefighters

raising the American flag above the shattered World Trade Center.

The image by Thomas E, Franklin of the Bergen Record (NJ) also appeared

in hundreds of papers worldwide. It garnered immediate attention—three

firefighters working intently, hoisting the flag on tons of shifting

rubble. They are covered with the ashes generated by the explosion.

The composition of the photograph is excellent: Three men evenly spaced

looking at the flag with concern. Their upward gaze, the position

of the flag and the large pole rising to the left-hand side of the

photograph makes it a memorable image.

The photograph brought out an immediate deeply felt reaction in America

as evidenced by the multiple printings, its use in impromptu displays

of patriotism and even in the demand for it as a tattoo. Its quick

embrace by the public based, in part, on the tragedy, the men pictured

and the flag’s appearance in a difficult moment reminds one of

another photograph made some 56 years ago in the Pacific on Iwo Jima.

The most famous photograph to come out of World War II was “Old

Glory goes up Mt. Suribachi, Iwo Jima,” by AP photographer Joe

Rosenthal. Five soldiers hoist a large flag on the high-ground of

Mt. Suribachi; they surge forward to plant Old Glory and their own

hopes during a battle just four days old.

The battle went on for another 31 days killing three of the marines

shown in the photograph. The men raised the flag on Suribachi, but

Suribachi was no longer a “mountain” in the natural sense.

It was a fortified mound filled with tunnels, Japanese soldiers and

artillery. It was a time bomb.

The Pacific war was difficult and deadly. Americans at home held on

day-by-day to see if the military would gain clear control of the

war. And then the flag went up against the odds.

The

image was transformed into a symbol of America’s determination

and confidence: the nation would rise above the moment and end the

conflict.

The

image was transformed into a symbol of America’s determination

and confidence: the nation would rise above the moment and end the

conflict.

Comparing the picture of the WTC and one at Iwo Jima, may at first

seem like a superficial coincidence of construction. But that is wrong.

The firefighters had lost approximately 200 comrades who had been

helping people in one tower to safety. They knew that they stood in

a space that had been violated, but also a space that was a sacred

grave of nearly six thousand bodies.

At the moment when Americans were numb and felt powerless, these men,

who had worked so hard, broke through the wall of despair and planted

a seed of hope, reminding Americans of the positive things they could

accomplish.

A major difference in the two photographs is the media that distributed

the information. The photo of Iwo Jima went from the battlefield to

American newspapers in approximately 17 hours—the fastest turnaround

time of a wire photo to that point. It seemed instantaneous.

The firefighters flag raising and much else that had happened since

the first terrorist-piloted aircraft hit the WTC, was seen in real

time. Much will be written on this catastrophe played-out in restaurants,

doctor’s offices and living rooms.

When the photograph of the flag raising on Iwo Jima was published

in 1945, the editors of U.S. Camera wrote that the “camera recorded

the soul of a nation.” No less can be said of the three firefighters

denying the panic and rising about the shock and chaos.

Marianne Fulton

Contributing Editor

marianne@geh.org