|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

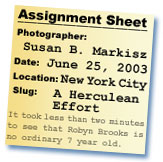

It took less than two minutes to see that Robyn Brooks is no ordinary 7 year old. Sure, her fire engine red painted fingernails, her constant companion, a stuffed animal named Patch, and a room filled with children's books with fairy tale endings, convey a deceptive sense of normalcy for Robyn, her parents and her 9 year old sister Elise, who moved to the United States from their small town in the UK last year. I only spent a few hours with them, but it was clear that Robyn's mom and dad, Karen and Garry, and her sister Elise, have the weight of the world on their shoulders.

Robyn, I had been told, is a spunky kid. Her dad Garry, indicated that the best time to come would be sometime around 7 or 7:30 in the evening, well after the narcotics Robyn takes, would have worn off. Robyn's best time of day is at night, he told me. We could not get permission, for patient privacy reasons, to shoot at Memorial Sloan Kettering during Robyn's treatments but it was a lovely June evening...still sunny, and breezy - with plenty of time for a walk in the park.

Ronald McDonald House has become the Brookses home away from home for the last year and a half. The room that the Brooks family occupies is about the size of a guest-room in the local Holiday Inn, with two double beds, a mini-refrigerator, microwave...all the comforts of home in miniature, you could say.

As I entered the darkened room, my pupils dilated. Blankets covered the windows to keep out the daylight so Robyn could finish sleeping off the narcotics that she has to take to stave off the effects of the painful treatments. I could hardly make out her tiny figure, bundled up as she was in a corner of the bed, her huge eyes peeking out from behind the blankets, her fingers clutching its satin binding.

Robyn was having a tough day. Still in a lot of pain, the last thing she wanted to do was to take a walk. What she did want to do, however, was to join her older sister Elise, who was playing bingo in the family room at RMDH. But it took every ounce of energy for Robyn to muster the strength to get going, and by the time we took the elevator down the few flights an hour later, bingo was over and Robyn was crushed. Returning to the room, Robyn's mom and dad read some of her favorite books. Her dad would tell her a joke or make funny faces, and Robyn's pale face would erupt in an engaging smile. Then, solemnly, stoically, he would share a detail or two about her illness. Although Robyn was eligible for the 3F8 clinical antibody trial, her family was ineligible for funding, because they are not American citizens, and they have racked up nearly a million dollars in debt. They have set up a website - The Robyn Brooks Appeal - to help raise money to help pay for their daughter's treatments.

Robyn had already had more than 100 blood transfusions in her short life, and she was soon facing another one. "She's pale," her dad said matter-of-factly, "she's going to need another transfusion soon," a little bit of stoicism in his voice masking concern..

Robyn's mom Karen was exhausted. I so wanted to say or do something to help, but there was nothing to say. My own cancer experience, 15 years ago, was fraught with its own difficulties, and fears. I know the exhaustion; I know the fear; I remember the stoicism. But it wasn't like this. It wasn't my child.

There was one other thing that I saw, though, out of the corner of my eye, that hit me like I had been kicked in the gut. It was Elise. Cancer is a family affair. It does terrible things to a family. There was Elise, her own childhood forever altered. If one were religious, or a philosopher, one could say she might grow up to be more sensitive, or maybe she will be motivated to become a doctor, and find a cure for the terrible cancer that afflicts her little sister. Perhaps. But what I saw with Elise, I saw happen to my own children. Much as my husband and I tried to make as normal a childhood for our children, it simply wasn't. In between ferrying my daughter to nursery school, my son to little league games and birthday parties, there were chemotherapy treatments. They were difficult but manageable. But there were also tears. I'm afraid I was not always as good at hiding things from them as I was from the rest of the world. My children soaked up my fears like sponges, and their body language at times spoke volumes about what was left unsaid.

Robyn and her family just came back from a vacation to Hawaii courtesy of the Make-A-Wish Foundation. Robyn fulfilled one of her dreams to swim with dolphins during her trip. She has recently suffered a relapse and her family and doctors are in the midst of deciding whether to discontinue treatments. For the Brooks family, the weight of the world just got a lot heavier.

© Susan B. Markisz

|

|||||||||||||

|

Write a Letter to the Editor

Join our Mailing List

© The Digital Journalist

|