|

They Call It Art: Campaign Photography

February 2004

|

|

|

|

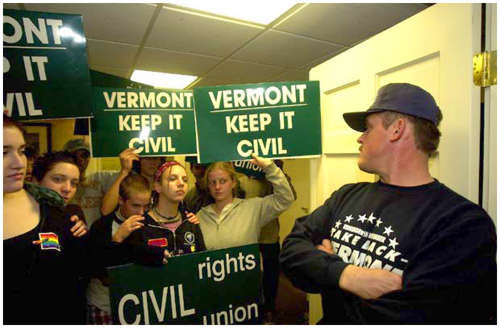

Political campaigns can be an exciting experience for photojournalists, and stressful for participants. Campaigns are put on to precisely deliver the campaign message, but a great deal of drama is involved; some staged, some unexpected. The important messages of the campaign must be delivered in a circus atmosphere. The planned spontaneity presents opportunities for the alert photojournalist. "Planned spontaneity" is not an oxymoron in political campaigns. Photojournalists look for the moments of truth revealed in the planned spontaneity. All journalists are on the scene to observe and listen, and report these messages. But, journalists go beyond passive pick-up-and-delivery, they judge the integrity and worth of what is presented. Vermont freelance photographer Steven Frischling caught a great moment of truth in this image taken during a Vermont political campaign. This scene may have lasted five seconds or several minutes. Frischling had to perceive this little scene while it lasted. Notice the expressions on the faces and the body language on the man. Is there bias in this picture? Are the students depicted sympathetically, while the sweatshirt man is not? If so, is this the photographer's doing? Or, did the photographer select a truthful instant to say something with his image? Consider these questions rhetorically. Frischling is an extremely fair and ethical photojournalist. Rest assured his image is as objective as his cutline, reproduced below the photo.

Photo by Steven Frischling Chris Crafts, wearing a "Take Back Vermont," anti-civil unions slogan sweatshirt, glares back at a group of students, involved in gay and lesbian organizations, as they peacefully protest a seminar set up to have the subject of homosexuality removed from schools in any context, as the subject of civil unions dominates Vermont's political debates, Wednesday, October 25, 2000, Brattleboro, Vt. Photojournalists enjoy an ambivalent position. One moment, they are perceived as Pavlovian observers, simply reacting and recording the pageantry, while reporters do the real business of the campaign, report the message. Other moments, politicians, the public and other journalist realize the camera is the most powerful recording instrument there, to be respected or feared. Photojournalists can flip from near-celebrity to pariah in an instant. This can be disconcerting to a newcomer. This up and down status continues when you present your work to the first critic, an editor. The editor trusted you with the assignment, so should trust your coverage, your hits and misses. You are not CNN, NBC, ABC, CBS, Reuters. You captured what you could. It's sad, but print editors saw the event on TV, while you where jostling for position, trying to make visual sense out of everything. Newspaper photojournalists are incensed by the "Did you get what I saw on TV?" questions. I met David Handschuh, former President of the National Press Photographers Association, at the Little League World Series in Williamsport, Pennsylvania. He was tired after a long day photographing games and color. He had transmitted everything back to his paper, the New York Daily News, and was ready to go to dinner. But, he got a call from his editors, "Go back and get a shot of the winning team in a tight happy grouping of heads, celebrating their victory." It was a great idea for an image, except Handschuh had earlier chosen to transmit action highlights of the victory. Going back to the ball park, finding the team several hours after their victory, setting them up in a jubilation shot was more than an interruption of dinner with friends. It was an insult to his professionalism. He was furious, but he got the shot and transmitted it. Later that night in my hotel room in another city, I saw the newsroom's inspiration for his shot on CNN. It was tape of their afternoon coverage of the championship game. Handschuh's editors had been happy with his action shots, but had ordered him to go back and get a shot they saw on CNN.

Photo by Tom Hubbard You can't be everywhere. Every great photojournalist has missed something highlighted in TV coverage. Politely stand by your coverage and defend it and sell it to skeptics. Writers and photojournalists observe and judge campaigns with their chosen tools. The action, drama, pageantry, emotion, and unpredictability make a campaign event similar to a sporting event. Paul Guillory of the Baton Rouge Advocate said, "In Louisiana, we consider politics a spectator sport." His sentiments are echoed around the land. The campaign manager and the coach, and the candidate and the star quartrback are parallels. Each may score a perfect delivery, or they may fumble. If the choreography is performed as planned, the intended message is delivered. But, truth may be revealed in the stumble, when the facade drops. That's what photographers look for. Images of a stumble will affect hundreds on the local level and millions nationally. "Stumble" is not always litteral. It can be anything visual that is off-message. This is where words may fail. Partisans may not believe the stories they read. But, they believe images, so, photojournalists are severely limited in access. Spectator Sport Politics as a "spectator sport" may be a joke, but it's instructive. The sports metaphor helps you to understand how photojournalists see their function, and how others see it. In sports, the competition is between two teams. In campaign coverage, the competition happens to be between journalists and the subjects they are covering. You are a sideline observer in sports, but you are definitely in the playbooks of campaign organizers. What you can see and capture is choreographed as tightly as the speakers, bands and placard wavers. Knowing this will help you maintain your position as observer, not participant. You are in their chorus, whether you like it or not. Just remember, they can put you in the chorus, but they can't make you sing their song. Political handlers want to manage a flawless event which follows the script. If the candidate gets close to the crowd, handlers want a sanitized crowd they have arranged or approved. To handlers, missteps are everywhere. A locally well-known unsavory character may be in the crowd, eager to shake the candidate's hand ... or worse. Mistakes can be more fleeting, until captured by the camera. The candidate may smile at an inappropriate moment. News is the exception, the flaw, the misstep. Handlers are trying to avoid these, or at least, prevent photographers from capturing them. Steve Frischling remembers campaign workers throwing 20 patrons of a diner out and replacing them with 15 hand-picked patrons, for a visit by their Presidential candidate. Frischling also remembers advance people scouring Boston all day for the perfect bar for a Presidential candidate's "spontaneous" visit. What handler or photojournalist would have thought there was a potential problem when President Clinton happened to casually embrace a women in a campaign stop? The image became famous when Monica Lewinsky became famous. Photojournalist Dirck Halstead didn't think much of the situation. He shot only one frame. One wonders if White House personnel may may have known the import of that moment when it happened? Halstead says he had no memory of the image later, when Lewinsky became a news story. But, he believes photographers have what he calls "lint on the brain." He said, "Whatever we have seen is lint on our brain. It can be triggered, maybe it was the red lips. I pushed the button. It was only a moment, one shot, no other frames of Monica around it." When Monica became famous, he had an assistant search thousands of negatives for the image he vaguely remembered.

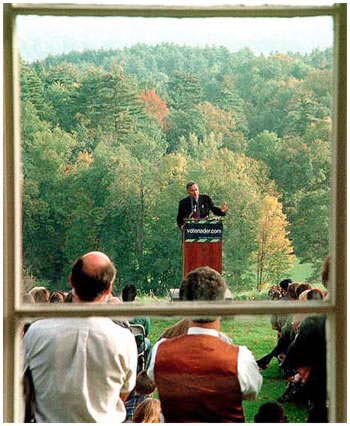

Photo by Dirck Halstead, Time Campaigns are a jumble of inconsistency, being precise and chaotic at the same time. The precision is in handling, from campaign flacks to the Secret Service. The chaos comes when thousands of people voluntarily or professionally participate in a unique pageant. Similar events have happened but not THIS one. It has never happened at this place or time before. The Secret Service is professional, as are seasoned campaign workers and journalists. The rest; new campaign workers, the crowd, hired security, are amateurs. I was one of a handful of journalists waiting for President Lyndon Johnson to land at the Cincinnati airport. It was during the Viet Nam War, at the height of Johnson's unpopularity. We were reluctantly allowed by the Secret Service onto the tarmac near where Airforce One would park. There were about eight of us. Everyone else was at the site of the President's speech. A Secret Service agent drew an imaginary line about ten feet long on the ground. He said, "Stay on this line, or we will have to jostle you." It was clear that "jostle" was an open ended term. The Presidential limousine pulled up and the angle caused me to be blocked by my colleagues on that line. The agent was watching us. I pointed to a spot two feet in front of me and silently asked if I could move there. He nodded affirmative, and I moved, and avoided the Secret Service "jostle." Another time, I was standing at the side of a narrow hallway, waiting for Vice President George Bush to come through. At the last minute, I decided to jump to the other side of the narrow hall. I was delayed for an instant because I stepped on a woman's foot. I was quickly apologizing when a pair of polite hands gripped the sides of my shoulders, picked me up, pivoted, and placed me out of the way. The script called for the Vice President to move through that hall at a certain pace. No time was allowed for a clumsy photographer to get out of the way. It was a physical and psychological tour de force by the agent. I was moved quickly and not upset. I stood in awe, staring at a Secret Service agent, about my size, wondering, "Did my feet leave the ground? Yes they did." The agent was my size, about 200 pounds. But, he had muscles to pick me up with his outstretched hands and move me. Try that with weights in a gym sometime. They forget the purpose The events above were handled well. The Secret Service protected their man and kept the event moving, without distraction. Give them your full respect, even if the amateurs get over-zealous. Ardent campaign workers often forget the purpose of a campaign is media exposure. Co-campaign workers don't communicate well. Journalists wonder if they talk at all. Confusion results, permission is granted one minute, denied the next. If you are denied reasonable access, keep asking. The next person may see a grander purpose, one that includes photojournalists. An important semantic note to remember is, never say you will "shoot" the candidate. Say "photograph." This may be a joke in the newsroom but it's a serious affair with campaign personnel. Campaigns are serious affairs for politicians, but quite humorous for journalists. They see the irony and contrast between the public presentation and the behind the scene shenanigans. President Ford had a knack for the misspeak and misstep. On a campaign stop in Middletown, Ohio, he constantly referred to it as Middleton. I got a laugh on the press bus when I said, "Oh, he'll probably correct it at the next stop in Daytown." These thoughts come directly from photojournalists interviewed for this chapter, but when they travel with a candidate, or the campaign comes to their town, photojournalists thoughts and concerns are more pragmatic. It's simple, "Will I be standing in the right place at the right time, will my view remain unobstructed and will my camera be ready? Reporters are ready if they are in the vacinity and have a functional pencil and pad, even if the pad and pencil are in a pocket or purse. If a surprise happens, only the photographers with cameras up to their eye, with the right lens, capture it. If reporters are distracted, they can whip out their tools and ask, "What happened?" Reporters deal with concepts and messages of the campaign. They weigh the candidate's position, and evaluate its intellectual delivery. Reporters appreciate photographers' efforts but seldom think of it as an equal report. After all, reporting is an intellectual activity. Wondering and worrying about where you will stand doesn't seem to match. Many reporters think photojournalists are just reacting to the scene, while reporters are doing the serious journalism business, evaluating what they hear. If campaign workers harrass or hinder photojournalist, it's a compliment. They recognize the importance of controlling the visual report. In the history of the world and human communication, this reporter bias is rare. Humans were communicating visually, with signs and gestures for eons before speech developed. The first "written" human communication was pictures. Photographers and mass audiences realize the prominence of visual communication. Reporters are trained to be outside of this intuitive communication. The NFL doesn't hire orators Political planners are ahead of reporters on this. In their planning, the visual is as important as the spoken message. Consider this. The NFL doesn't hire orators to sell their action. The action and the emotion sell football. Political campaigns are the same. Ralph Nader has never been known as an exciting campaigner, but look how campaign workers planted "green" in this appearance in Vermont. Notice that freelancer Steven Frischling had to accept the campaign "green" message, but he gave it his individual framing.

Photo by Steven Frishcling Important information is communicated visually. Campaign organizers recognize this all too well. They organize a visual tableaux, designed to augment the campaign. Campaign people script an event. Photojournalists know they are manipulated. Their job is to break through the manipulation with planning and intuition. Secretly, they respect their own creativity. Intuition and creativity are not respected journalistic tools, but they ARE the tools of photojournalists. A campaign visit is exciting. The atmosphere is created to persuade the crowd to "buy" the appearance, and the message. First, comes the anticipation of seeing the famous candidate. Bands play. Cheerleaders work up the crowd’s enthusiasm. Sometimes the cheerleaders are from a local school, other times they are carefully selected groups of enthusiasts. The photojournalists is in the middle of this, a part of it, while trying to be an impartial observer. Good photojournalists create a psychic envelope around themselves. They let their psyche function on both levels. They embrace the excitement on one level and evaluate and observe it on another level. Most can't express this, or even conceive of it, but it's how they do it. If you have a chance to observe a press pool of reporters and photographers before an event, you may notice reporters are generally relaxed and socializing with each other. Photojournalist pretend to be relaxed, chatting, bantering with each other. But if you look closely, photojournalists are nervous before an event. This day, they may get a great shot or they may not. Their preparation is more psychic perception than intellectual. Most photographers fear missing the important shot. Some deny this fear through preparation, including everything from checking equipment to getting a good safe shot early. Then, you can take some chances. Relax. A relaxed finger on the shutter button is a key to great photographs. Photojournalism is more intuitive than most are willing to admit, but there is a chance to intellectually prepare. As you prepare to photograph a campaign event, review what you know about the situation. You might start with your access and the physical environment. Can you get there from here? It may be easy access on normal days but how wide is the security perimeter? Can you park and get there on time? Notice, the best photographers are first there. Who put the sun behind the stage? Is the natural lighting right? Can you avoid shooting into the sun? (Amateurs may have placed the stage.) Will stage lighting give you problems? The most important question may be, what makes this situation unique? Use that uniqueness as your theme. Be flexible. Shoot what occurs, but frame your thinking. Politicians can be compelling personas, but don't forget the environment. That great close-up in your viewfinder may be identical to one taken yesterday in another state. Will security come up with a last minute restriction, thwarting your plans? Are you tall enough, or can you stand on something? A small ladder is standard equipment for many campaign photographers. Are you prepared, with elements you can’t photograph? That is, have you read everything available on this event? You can't photograph the issues, but knowing them will cue your reactions. Know if the candidate is strong or weak with any issue or demographic group. Keep an eye on such groups and anticipate protests or support. You may want to be in the middle of this group or nearby for close faces that make the dramatic pictures. We are dealing with cosmic elements of campaign coverage here but an equally important question for photojournalist, is my stuff ready? Stuff is everything needed, from cell phone to notepad to laptop to camera equipment. Is each lens in an intuitive spot in my bag or vest? Do I have a snack, in case I’m tied to the campaign for hours with no food stops? Most campaigns are aware of journalists needs for food and other amenities, but campaigns are chaotic. (Photojournalism veterans agree, Republicans serve better refreshments than Democrats.) Push-top writing pens are best. There's no time to remove a cap to write notes. Wear sensible shoes. Two stops in a candidate's leisurely walk around may require equipment laden photographers to run the length of a football field to be in place for the next "op," and no one anticipates this. You are a professional, so dress the part. You are not going to a beach party or pickup basketball game. You are mor than a camera, so dress the part. A shirt and tie and decent slacks for males and the equivalent for females is acceptable attire for most public events. Washington photographers wear tuxedos and formal dresses at evening events. There's an inverse wisdom in dressing like the crowd. The more you blend visually, the more chance you have to be an individual, by not drawing attention. Finally, have one deep thought, what will I do today? In the long history of the world, or this campaign, or my community, what do I want to record and show today? Have a theme, but be flexible. You can change, drop or forget your theme but it gives a proactive base to your thinking. You are more than a drop of water, dancing on someone’s pancake griddle. "I told him I would try." Paul Guillory, then a photographer with The Advocate in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, met these arguments head-on, as a photographer should, with his camera. Clyde Holloway, a Congressional candidate was re-districted to the far end of his district, far away from its center. The Holloway complained that he was not getting a fair ride and demanded to be included in the picture this time. Guillory responded with a few words. He said, "I will try." Did Guillory do it? You decide. Here's the picture.

Photo by Paul Guillory, the Baton Rouge Advocate

Practice reverse reaction What if the unthinkable happens, something terribly unexpected? You can't really prepare for this. For your emotional health, you probably should not obsess on such possibilities. A good preparation is to practice a reverse reaction to events. The more exciting the moment, practice being calmer. Try it. Find an exciting event and determine to remain calm. Even in a heated discussion with a friend, find a quiet place within, and retreat there. Practice not hearing, at a speech or rock concert or exciting sports event or movie, even walking down the street. This teaches you to ignore what you can't photograph. If you are familiar with Zen, you will recognize these techniques. If not, spend a couple of bucks on a Zen book at a used-book store. Photojournalists with years of experience remember the value of intuition. Campaign security has been observably tightening over the last 50 years. Earlier photojournalist could wander the scene, stand back or get close, have lunch or champagne with the candidates. Today, campaigns are more precise. They may look casual but most are precisely timed. If you photograph popular celebrities, you just might get a movie star to tarry for more photos. If a national politician tarries, it was in the script. Unique from the start Photojournalists are charged with getting unique images, much more than reporters are charged with getting a unique report. Only the most trusted experienced reporter is allowed to make a unique report. Photojournalists must do it the first day on the job. To reach this high plane of uniqueness, photojurnalists must attend to the mundane. They must have the right credentials for this visit, and their credentials must allow them access to photo areas. The newsroom usually arranges for credentials, and often ignore photojournalist's needs. For example, for gruesome reasons, photographers want to be outside, near the runway when the President's plane lands and takes off. If the weather is bad, reporters may be just as happy to watch from inside. Those ordering credentials should be aware of photographers' needs. The physical wearing of credentials has aspects to consider. Most photojournalists have a favorite sturdy clear plastic credential holder they got from some assignment. It's usually about 4 x 7 inches, on a neck strap. Fed X might be happy to ship you around the world with such clear identification. With camera bags and several cameras around the neck, the type of chain can be important. The ubiquitous metal link chain can pull and cut. Credentials on the camera bag may not pass security, or be pulled off in a crowd. My favorite is a loop of leather boot string. It will not break and never cuts or gets caught in hair. Photojournalists seem to be watched by security more than anyone. In frustration, photojournalists have avoided credentials and just joined the crowd. Mark Hertzberg, with the Racine, Wisconsin Times Journal tested this. He got a public ticket from a Democratic friend, borrowed his wife's point and shoot camera, and showed up for an Al Gore Vice Presidential visit. He got closer and more dramtic shots than the Journal staffer stuck on risers.

Photo by Mark Hertzberg, Racine, Wisconsin Times Journal Some security access restrictions may seem arbitrary, until you understand their thinking. If you have been cleared (searched) and are in a secure area, you cannot casually leave and come back. The search was clearance to enter this one time, not a personal approval of your charming personality. Once outside the area, you must be cleared again. Think about it, it's logical. Never leave your camera bag. Any unknown bag or container is a security crisis. At some point, review your biases. Are, "all politicians crooks?" Are you predisposed toward male or female, young or old candidates? Politicians build a public persona. You walk a fine line between "buying" this persona and ignoring it. "Buying" might be an exciting image. Ignoring or working around might be an exciting discovery, or a boring shot. You are not a cheering squad. Laugh at funny lines and applaud only politely, so you don't draw attention to yourself. Remember your position as an observer. Reporters strive for objectivity. Be objective in your behavior but your work should be honest more than objective. Objectivity can defeat your purpose. After all, you are looking for excitement and emotions, opposites of objectivity. Your best bet is a centered, flexible, emotional stance. Find the dominant emotion, feel it, look for visual display, in the sense of behavior and juxtaposition. For instance, if you see a supporter or detractor dressed as Abraham Lincoln or a giant chicken, decide whether it is honest enthusiast, or something done for you. Dismiss thoughts of how you might vote. You are there as a journalist now, not a voter. (Some journalists never vote, to maintain their objectivity, but this may be extreme.) The camera can lie The camera can lie by delivering a visual ambiguity that is filled in by the viewer. Mark Hertzberg tells us the story behind this picture. Vice President Al Gore appears to be walking off the plane, waving to the crowd. Gore is walking, but the crowd is three photographers.

Photo by Mark Hertzberg, Racine, Wisconsin Times Journal Be aware that dramatic, telling images may be second guessed by the campaign ... in advance. Campaigns are repetitive. You are looking for new drama. Campaign directors will exert pressure on editors for favorable coverage. They may question the validity of an image. They may see you capture an unflattering image and call your editor before your picture gets to the newsroom. You can argue that the camera can lie and can tell the truth. Campaign workers want it to be their truth. David Kennerly, shooting for Time, had to justify a revealing portrait of a haggard President Nixon, at the height of the Watergate crisis. The picture itself became news because it it caused many in Congress to think Nixon could not make it through the Watergate crisis. AP got many calls questioning the objectivity of the photo. AP criticized Time at an Associated Press Managing Editor's convention. Time looked through Kennerly's negatives. All of Kennerly's 36 exposures showed little variation in Nixon's haggered look. Kennerly had not captured an unfair, unrepresentative moment. It's a lesson. Be ready to prove your image is accurate in reporting the tone of the event, or the moment. An emotional tear is different from a dust in the eye tear. Both may be part of the campaign story, but be sure to present them fairly, even if in the cutline. When the candidate and entourage get into limousines and vans, be there. It's still a news scene, even after they leave. Be there, unless a compelling deadline draws you away. So, how's it done in the United Kingdom?

British Prime Minister Tony Blair by Neil Turner, the London Times British photographers face the same situations as American photojournalists, with a few exceptions. The United Kingdom is a smaller area, so a candidate's travels seldom last more than 48 hours, and are usually one-day long. Neil Turner is a photojournalist with the educational edition of the London Times. He often travels in his own car, even on general election campaigns. He likes having all his equipment with him, and he can transmit via his laptop from his car, and drive home. Fatigued American journalists on the campaign trail would appreciate this luxury. American photojournalists are experiencing one new problem that Turner is familiar with. He said, "The risk of terrorism in the UK has been huge for all of my adult life, so the security is always tight. I always have an eye for terrorism." In typical British understatement, he said, "I am always nervous of the very big set-pieces and their attractiveness to those who want to bypass the constitutional process." As it is in the United States, there's more freedom on the smaller campaigns. The amateurs are abroad also. Turner says, the UK Police are pretty good so most problems tend to come from private security. He understands some restrictions, "It's a lot easier to do (visual) damage to a campaign than it is to help it. It only takes one off-guard moment to ruin a candidates hard work for that day." Turner and his photojournalism colleagues made a rare show of solidarity in the Prime Minister's general election campaign. Turner said, "There was a good deal of frustration amongst photographers so we staged a series of 'cameras down' protests and turned our backs on 'photo opportunities' to let the PRs know that we were fed up with their controlling ways. The picture desks of all the national newspapers were behind us and even ran the story!" Like photojournalists everywhere, he has concerns about missing a shot, but he's not too worried. He said, "It happens to everyone, so I tend to trust myself to get the picture 95 times out of a 100 and trust in Reuters for the other 5!" The campaign manipulators are everywhere. He said, "They always try, but we are too creative to be bound by their rather clumsy efforts." He makes an important point in this e-mail message about more subtle manipulation.

President Clinton came to Madison County Ohio to speak at the Ohio Peace Officer Training Academy in Madison County, near Columbus. Jane Beathard was a reporter for the Madison Press. She saw things the national press see all the time, but don't notice any longer. First, she noticed, President Clinton moves and talks very slowly. "I wondered how a guy who moves so slowly gets to be President?" Then, she noticed Josh King. Jane said King was a short chunky man in a raincoat. King's name seemed appropriate for someone directing the President. He was always just out of camera range, helping Clinton stop some distracting physical quirks. Clinton has a tendency to slouch, and to touch his teeth with his tongue. King would stage whisper or use hand signals to direct Clinton to straighten up, etc. Jane was amazed that Clinton's physical actions were so obviously directed. The scene was arranged to visually tell the message, even to those who did not listen to Clinton's words. They had invited all the 88 county sheriffs in Ohio to hear the speech. The sheriffs were specifically asked to come in uniform. Being sheriff is an executive position. They usually wear civilian clothes, except when making statements to the media. The sheriffs sat in bleachers behind the President. All the still and television images showed the President backed up by police officers. President Clinton ended his day by stopping at a meat market advertising "Clintonburgers." The place was known to the local press. It had been cited for numerous health violations and had an employee wanted by police in another state. Guess what the evening news story was that night. The very smallest mis-step can blossom into the big story of the day. Big things happen in small towns, and big things happen away from the speaker's stand. Political handlers know this, so they must be specific, even arbitrary. The next time you sense you are being manipulated, have a little, just a little, empathy.

© Tom Hubbard

|

||

|

Write a Letter to the Editor

Join our Mailing List

© The Digital Journalist

|