|

| ||||

Temp Shooter, Major Disaster

January 2005

|

|

|||

|

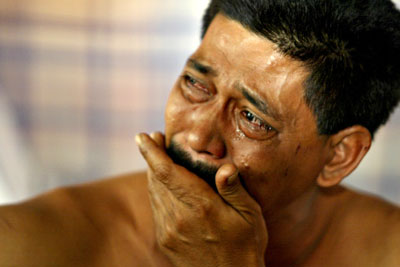

"What is wrong with you? You're filing your pictures late! We're getting killed by the competition!" yelled Yves, the Agence France-Presse photo chief in Hong Kong, through my cell phone. "And why are you sending us so few pickups? Are you doing your job?" he added. It was December 27, a day after a tsunami struck northwestern Malaysia, one of the many countries the wave hit, inflicting a death toll of more than 120,000 people worldwide. That statistic continues to rise by the day. I am on the ground in Penang, one of several areas in the country hit by the giant wave, and quickly reaching my personal breaking point, running a high fever from the flu I contracted on Christmas day. That and the simple fact I was the new guy: AFP Kuala Lumpur hired me one week ago as a temporary shooter for their photojournalist who needed an extended vacation. I had the skills from several years working for community papers in the United States and a self-funded project in the Indian Himalayas (where I did string for AP every now and then), but I did not have the years of experience to do wire service work on a daily basis. I eagerly accepted the job offer; I wanted the work experience, even if it was just for six weeks. "It's all pretty simple, just make sure you get some good stuff every couple days, file them in a timely manner, and cover the important events. Malaysia is a somewhat slow news country, so don't worry too much" said Jimin, the AFP staff photojournalist, before he left for vacation. He was later sent to Sri Lanka to cover the tsunami aftermath. "And don't forget pickup photos if you can't physically cover any assignments by yourself," he added. He was wrong on the slow news thing, and I misjudged the importance of additional pickups during disaster situations. While other wire agencies had their shooters on the ground and deskers at bureau offices sourcing pickup photographs, it felt as if I was the only photographer doing both tasks. I found it hard to juggle shooting, filing, finding pickups, and being in three places at any given time, plus a fever to nurse. Apart from the help of my correspondent and other photographers in the disaster area, I was totally alone, trying to manage my own little crisis on this end. Hong Kong, furious at me, didn't know that. But would it matter even if they did? I fell asleep late that night feeling annoyed and shaken. I couldn't afford to lose my confidence, the temp shooter trying to prove my worth, doing my darndest, while trying to keep a level head. We took off after an early breakfast the following day, December 28, looking for more tsunami aftermath. I was beginning to grow a little tired of static photographs of smashed houses and displaced boats. For some reason my photographs weren't telling the destructive force of the tsunami. Perhaps it was because Malaysia suffered very minimal casualties compared to other countries (sixty-six people have died in Malaysia, with several others missing--a tremendously small number compared to Indonesia or Sri Lanka). Or perhaps I was simply in the wrong places at the wrong time. Whatever it was, it came to a point where my photographs were getting repetitive. I needed something stronger, something more compelling from a human perspective. Jega, the correspondent I was working with, was given the address of a grieving survivor somewhere near Balik Pulau. We decided to look him up. We got lost along the way, and stopped to ask for directions. An elderly man who was filling up his motorcycle at a gas station offered to lead the way to the person's house. Arriving at the village, there were a few curious onlookers checking out who we were. It seemed that the local media circus had come here the previous day, hounding the politicians that seem to materialize out of nowhere, important ministers discreetly fighting with each other, highlighting their concern, only to disappear as quickly as they showed up, motorcades kicking up a trail of dust from drying silt and mud churned up from the tsunami. I was glad we were the only outsiders there, without the mob of other reporters and photographers. It made it easier to interact with the villagers on a personal level, to take the time to listen to their stories. It felt real. And it felt right. We were brought to the house of Zulkifli Mohamad Nor, who lay on a thin mattress in the living room surrounded by grieving family members. He was in physical pain after the wave carried and smashed him on the beachside rocks, but that was nowhere close to the pain he carried inside: Zulkifli lost five of his seven children to the tsunami while he and his family enjoyed a Sunday picnic at the beach.

Kate, my girlfriend, called long distance from Pennsylvania later that evening. Or was it me who called her. I can't remember. All I remember was breaking down after talking with her for a minute or two. "I just photographed a father who lost five of his seven children. The poor guy doesn't even have a complete family anymore," I said as I tried in vain to regain my composure. I couldn't even describe to Kate how it felt while hearing his story, the trust he had given me being there with a camera. I also learned that evening that my second cousin, Cara, was one of the many casualties of the tsunami--she was listed missing for days, and recovery personnel only just recovered and identified her body. She was up in Phuket, Thailand, enjoying a vacation with her family when it struck. Though I have not seen her since my early teens, the thought of her in those frightening last moments gave me nightmares. It is now New Year's Eve as I write this. Abdullah Ahmad Badawi, The Malaysian Prime Minister, has made a call to cancel all New Year's celebrations, replacing them with gatherings of prayer and reflection. Meanwhile, I am still in Penang, continuing coverage of the disaster. I have seen survivors gather whatever is left of their belongings from their destroyed homes, photographed them sleeping on concrete floors of cramped classrooms in schools converted into relief centers, listened to their tales of grief and survival, and empathize with their growing frustrations of not yet receiving any meaningful assistance from the government or independent aid groups. I reflect on how I handled the job during the disaster. I made some mistakes along the way, some that I wished I didn't make, but given the circumstances I think I did an okay job. I don't think I could have done much better, but I still can't help but wish that I did more.

© Tengku Bahar

Dispatches are brought to you by Canon. Send Canon a message of thanks. |

||||

Back to January 2005 Dispatches

|

|