|

→ January 2005 Contents → War Stories and Legends

|

With Nixon in China

A Memoir January 2005

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

I have been a working news photographer and photojournalist for more than 50 years. During that time, I have covered wars, royalty, movie stars, and spent 30 years covering The White House. But if I had to point to one story that was the most important I ever covered there would be no doubt as to the winner: the trip of President Richard Nixon to China in 1972. I had covered the Nixon presidential campaign in 1968 for UPI and during the next four years, although I was then based in New York, I was frequently asked to cover Nixon's major international trips. In July of 1971, while Nixon was summering in San Clemente, a bombshell went off. It was revealed that National Security Advisor Henry Kissinger, who had mysteriously disappeared after the president's arrival in California, had secretly flown on to Beijing, and had gotten an agreement from the Chinese to invite President Nixon on a state visit the following year.

China had been sealed off from the West since the Cultural Revolution. With the exception of a few left-leaning western journalists, no western press had been allowed to enter what was called "The Middle Kingdom." As you might imagine, once the announcement was made, every journalist in the world started to jockey for position to be included in the presidential delegation. That was the main question asked at press secretary Ron Ziegler's briefing: "CAN I GO?" When Kissinger had conducted his negotiations with the Chinese, the makeup of the press corps that would cover the visit was not a priority. As the meetings concluded, Kissinger was told that of course Chairman Mao would welcome the press with the president's party. They had in mind ONE print reporter, preferably from The New York Times. Kissinger's people tried to explain to the Chinese that photographs and television were of supreme importance in the West, but it became clear that was not the time to press the issue. So you can imagine the bedlam that broke out in the press briefing room when Ziegler announced that the Chinese had decided to allow one print reporter on the trip.

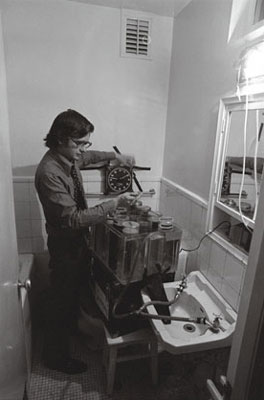

For the next several months, every news organization was turned into a Shakespearean battleground, as reporters schemed to be one of the chosen few. The gloves came off. Any one of these people would happily drive over his or her own mother to get on the plane. Eventually, the Chinese decided to allow a total of six still photographers to accompany the president. But since they had no real experience with television news, they did not think it was necessary to include the networks. This led to pressure from the very top of those organizations, but the Chinese would not budge. Finally, an ingenious advance person on the ground in China came up with the perfect pitch. "Television is not really considered press. What these people do is provide technical support." This made sense to the Chinese, so at last television would be represented. There was a caveat, however. The Chinese desperately needed modern communications. Therefore, it was agreed that every piece of equipment the television people brought into the country would be left behind, in operating condition, including ground stations. This then led to further bloodshed at the networks as correspondents and crews fought to be included. Of course, the big guys (and girls) won. Walter Cronkite could go, as could John Chancellor, and the correspondents such as Barbara Walters. During this time I made innumerable trips down to Washington, where I wined and dined my friends at the White House. Eventually the six photographers chosen were John Dominis, representing Life magazine; Wally McNamee, Newsweek; Bob Daugherty and Horst Faas of The Associated Press and Frank Cancellere and myself for UPI. In addition, two "technicians" were allowed to go to China in advance and set up transmission facilities: Bill Lyon, who was then the general manager of UPI, and Bill Achatz from the AP. IT'S GOING TO BE VERY COLD The selected press then received a number of briefings in Washington. We were warned that a Beijing winter could be very cold. We all received various inoculations, and were told to go out and buy warm coats, and several sets of long underwear and thermal socks. We were warned that anyone who got sick would immediately be sent to the hospital, and might not make it home. In pool meetings, we were also told that we should expect no sleep during the six days in China. Everyone would have to do double and triple duty. As well as shooting, each of us had additional responsibilities. For example, each night after a long day covering events, I would go into the darkroom we had set up in the Minzu Hotel and process not only our black and white but also color film, not just for UPI but for the magazine pool, as well. I then had to make dupe slides of the selects that would be put on a courier aircraft at dawn to be sent to the pool headquarters in Tokyo.

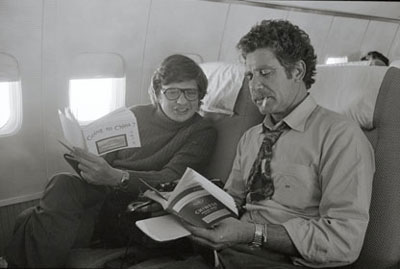

On the red and white TWA jetliner were the greatest names in American journalism: CBS' Walter Cronkite; John Chancellor, NBC's anchor; Theodore White for Time/Life, who had written the definitive book on Mao's long march; novelist James Michener; Eric Severaid of CBS; William F. Buckley of The National Review, and the fabled Hugh Sidey, keeper of all things about the American presidency, for Time/Life. Somehow, ABC's Barbara Walters wound up on Pan Am, and she sulked throughout the flight to China, especially when occasionally she would look up through the window and see the NiHao 1 flying proudly overhead. OPENING THE MIDDLE KINGDOM As the planes crossed landfall over the People's Republic, the normally blasé travelers jostled to take pictures through the windows. You have to remember, no Western journalist had seen this country pass below for more than 30 years. The charter planes arrived to clear formalities in Shanghai, the port entry city to China. From there, we would go on to Beijing on Chinese aircraft. Our planes would follow behind, empty.

White House advance man Tim Elbourne told me of working alone in China throughout January, and then a week before we were to arrive, he went out to the airport to see the arrival of the first jumbo Air Force planes. As he was standing with astonished Chinese who had never seen a plane of such size, the back of the plane opened up, and a huge truck lumbered out with the proud insignia of NBC's peacock all over it. As the Chinese watching gasped, Elbourne's heart swelled with pride, and he began to weep. We arrived at Beijing's International Airport 18 hours ahead of the president. As we drove into the city on buses, we were all busy taking pictures out of the windows. The streets were covered with snow, which workers with brooms were trying to move to the side. The most astonishing thing was there were no cars. There were some busses, but everyone else was on a bicycle. It was very cold, but the main thing you noticed was the acrid smell of coal that was used for heating all the buildings. Arriving at the hotel, we were all introduced to our "opposite numbers." The Chinese had made sure that every reporter, TV technician, and photographer had a "minder" who would stay with them 24 hours a day. In addition to keeping track of the foreign press, the job of these "minders" was to learn how to do whatever it was that their guests knew. My minder was a government photographer, who would constantly ask me what exposures I was using, and what my film speed was. My favorite example of one of the minders in action was one that was assigned to the pool TV producer, staying at his elbow for the entire visit. Early in the coverage of the presidential visit, he turned to his American colleague and said, "I understand almost everything you are saying. The feed, the uplink, the standup, but there is one thing you keep saying that I don't understand. Please explain, what is "the F...g Audio?" NIXON IN CHINA On the morning of February 21st, we were all bussed out to the Beijing airport for the arrival ceremony. As we stood on camera stands in the frigid cold, we watched as Chinese soldiers raised the Stars and Stripes alongside the Chinese flag. President and Mrs. Nixon were greeted by Premier Zhou En-Lai, and did a formal review of the honor guard, then took honors as the American and Chinese national anthems were played. I photographed the ceremony from a camera stand, while my colleague Frank Cancellere, who had arrived on Air Force 1, took close-in pictures.

I have discovered in most of the old Communist countries that there is a saying when asked if it is possible to cover something. It goes like, "It's no problem! It's impossible." The agenda the Chinese had laid out for coverage was naïve. They actually thought they could control the movements and coverage of a modern American White House press corps. They soon learned otherwise. The sheer technological modernity of the American coverage left them speechless. Suddenly young network pool producers were telling senior Chinese bureaucrats how many minutes they had to get across the message on The Today Show. And of course, they had never met anyone like Barbara Walters. The barbarians had indeed crashed through the gates! President and Mrs. Nixon were staying in an official Chinese guesthouse not from the Hall of the People. The president's movements were to be covered by the small White House traveling pool, which included Cancellere and Daugherty. They rarely got into position to do any of the major events. The rest of the press were bussed ahead of time to the events, to pre-position. Today, on a similar state visit, the pre-positioned pool would number in the hundreds, but in China, I doubt there were more than 20 photographers in the room.

Everyone on the trip, regardless of whether they were White House staff or press, was considered part of the "official U.S. delegation." That led to something I had never seen before or since, when there really was no "press," but everyone on the trip was treated equally. At the major banquets, we all sat at large tables, and we each had our Chinese counterparts to the left or right. When toasts were given, it was appropriate that the press participate, and walk around the table, toasting each member at the table. The drink, by the way, was Chinese "Mao Tai," a highly combustible rice wine that was essentially "sake" -- times ten. We watched as President Nixon made a painful attempt to use his chopsticks on his Peking Duck. The Chinese were major cigarette smokers, and packs of cigarettes were in front of every place setting. On the evening of the American reciprocal banquet at the Great Hall of the People, the White House had arranged for California wines and champagnes to be served. They also provided packs of American cigarettes with the Air Force One seal on them. A few minutes after the guests sat down at their tables, a murmur began to arise from the room. Chinese were whispering to each other and pointing to the cigarette packs. This was their first introduction to the concept of "The Surgeon General states that smoking these cigarettes can be harmful to your health." Generally, when covering a White House trip, there is very little suspense about what is going to happen. The advance teams for both sides have really worked everything out, and it is only necessary for the principals to take their positions for the photo ops. Twice in my career, I have seen entirely unscripted summits. The most recent was the meeting between Mikhail Gorbachev and Ronald Reagan in Reykjavik, Iceland, where everything suddenly came off the tracks, and the meetings between Nixon and the Chinese. Although Kissinger and his opposite numbers had prepared the playing field as best they could, you were still left with arch-enemy of the West, Chairman Mao, and Richard Nixon, a conservative from Yorba Linda, California. How these two men would find common ground was a question that tantalized the most brilliant minds in statecraft. In this case, a possible realignment of world politics was at stake.

Then there was the Great Wall of China. We were bussed to the wall, half an hour from Beijing, and waited in the cold for the presidential party to show up. The president and first lady, accompanied by Secretary of State William P. Rogers, walked on the wall to our cameras. A reporter cried out, "Mr. President … What do you think of this wall?" After thinking for a few moments, Nixon responded, "It's really a Great Wall!" For six days, the schedule was packed. We would be bussed from one event to the other, then back to the hotel to drop off our film, then back on another bus. Every night there was a dinner, which would go on until nearly midnight, where the Mao Tai flowed like water. Then it was back to the darkroom for another five hours of work, processing and making dupes. After the second day, I had adopted a routine. I would come back to the hotel, drop my coat off in my room, and take a shot of Jack Daniels. Then into the darkroom to start the color processing. About 3 a.m., I would go back to my room, take another shot of Jack Daniels, and a clementine orange, then back to the darkroom to start making dupes, finishing about 5 a.m. in time for the courier packet pickup, then get an hour's sleep, and be in the lobby at 7 a.m. for the next day. After four days of this, as I came out of the darkroom at 3 a.m., my erstwhile opposite number, who had to keep track of me, stumbled over to me and wailed, "Please, Mr. Dirck, you must get some sleep! You will die if you don't!" So, it was in a state of complete exhaustion that the press corps approached the end of the visit. We were about to fly to southern China for a brief visit, which Premier Zhou En-Lai was hosting. Before arriving in China, almost all of us had filled out forms requesting that we be allowed to stay after the president left. As the time approached to leave, we became panic-stricken that the Chinese would take us up on our requests. We were totally exhausted, and all we wanted to do was get back on our friendly U.S. planes and go home. Word spread that Chinese officials were walking through the hotel offering visits. We all locked our doors. As we got ready to leave the hotel, we decided to pay one last joke. We all had these smelly sets of long johns. So we dropped them in the room of one highly-paid TV correspondent, on her bed. At the final departure ceremony, as the correspondent was in line to say farewell to Premier Zhou, an assistant came bustling up, saying, "Excuse me, Missus, but you left these in your room." Thinking it was a parting gift, she opened the package, and the odor of scores of fruity long johns filled the air. Back on the "Zoo Plane," Pan Am, which had been waiting in Guam for us to exit China, had gone to great lengths to provide a festive return to the United States. They had decorated the plane with balloons and signs, and brought aboard the finest food and wines. The 707 had barely cleared Chinese airspace when the dismayed flight attendants looked back into the cabin, and it looked as though someone had released sleeping gas. The entire press corps was dead to the world, and would not regain consciousness until the planes settled to earth at the Anchorage Air Force base. It had been a week that literally changed the world. The following year, peace talks started in Paris to end the American involvement in the Vietnam War. China, and then the Soviet Union, started to dramatically reduce their arms shipments to North Vietnam. China began to pursue free trade and consumerism. Within a few short years, those streets that had seen only bicycles were filled with new cars. Two decades later the Berlin Wall fell, and the Soviet Union, now a broken military power, was no more. Two years later, Richard Nixon left the White House in disgrace. But by that time he had negotiated the crucial SALT treaty that ended the nuclear arms race. And all these things came about as the result of one cold week in The Middle Kingdom.

© Dirck Halstead

Editor and Publisher of The Digital Journalist

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

Back to January 2005 Contents

|

|