|

→ March 2005 Contents → Column

|

"First Seen"

March 2005

|

|

|||||||||

|

That we live in the digital age is undeniable. Digital touches every part of our lives, especially in photography. We should never forget there was a time when digital was beyond anyone's imagination. In 1839, and for many years after, when photography was still new, photojournalists did not exist.

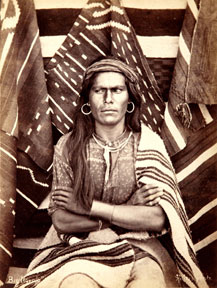

So, come back in time with me, perhaps as long ago as 165 years. Take a journey with me to Kabul, Algiers, Syria, Egypt, Burma, Turkey, and Kashmir. Visit these and many other exotic locations over the world, at the Dahesh Museum of Art in New York and its new exhibit, "First Seen: Photographs of the World's People, 1840-1880." The next time you press the button on your digital camera, whether professional or amateur, think about this exhibit. Viewing it will help you understand modern photography, and give it context and historical meaning. The 250 photos in this remarkable exhibition are about faraway places distant in time when the camera was a magical new instrument. Few understood how it worked. Even fewer could afford to own one, let alone use it. Photography was in its infancy and the people who took pictures were amateurs. But these men saw something in the new device that fascinated them, something that would allow them the chance to stir their creativity in ways they never imagined. Given the opportunity, they bought and provisioned rigs and then went trooping the world in search of what their roving eyes could bring to those who had to stay at home and were not as fortunate as they were.

It is important to see this exhibition as much for its history as for its art. Initially, many of these men were official photographers on military expeditions sent to explore, and possibly subdue, what many then considered inferior peoples. Some were on the road with their unwieldy equipment to record the ethnic diversity of an exotic way of life. Art was probably the last thing on their minds. Many thought only of the historic record they were mapping, using photos about a world no one had seen to that moment, and one we will never again see. Others understood the commercial appeal and their photos appeared in albums sold to a public entranced with exotica. Photography was too new to have developed a formal methodology on how to take pictures. There were no instruction books. There were no classes. Those would only come with time. I wonder if these photographers knew the work of each other. How many of them knew each other personally? Did they exchange ideas about technique? In London or Paris 150 years ago, did they discuss their adventures while sipping ale or mulled wine in their pub or exclusive club? Certainly each must have made many discoveries on their own. Many years later, once out of the bottle, photography advanced rapidly and meaningfully to become an important part of our lives. Ideas about art and method flowed, and still flow, through intellectual commerce and open exchanges. Now the equipment is so small that were we to bring one of these photographers to this day, they probably would not believe the size of the camera. One they could hold in their hand. The next time you, as a professional or amateur, point and shoot your new digital camera, whether a photojournalist on assignment or at a wedding of a friend, think back to the past and what the early photographers had to do to make a record of what they saw.

These photographers set the standard for today's photojournalists.

© Ron Steinman

|

||||||||||

Back to March 2005 Contents

|

|