|

→ June 2005 Contents → Feature

|

The News from the Dark Side

|

|

|||||||||

|

If you think it's tough being a photojournalist, try being an author. According to publishing industry statistics about 60,000 new book titles appear in the United States each year, most of them going directly from the warehouse to the remainder piles with only a brief rest on the shelves of a bookstore. In an attempt to counteract this downward flow their creators have to go through one of the most grueling and demeaning experiences known to mankind the book tour (something that is not, but should be, covered by the Geneva Convention.) This can take several forms, the least effective of which is actually going to Des Moines, Cincinnati, Minneapolis and other key towns where people still buy books. It's the literary version of a trunk show. A better way to flog your product, or so I'm told by my publisher's publicity department, is a satellite tour where you sit in front of a phone and radio stations around the country call you for live or taped interviews. It's also one of the most tiring and disorienting ways to spend a day short of running three back-to-back marathons.

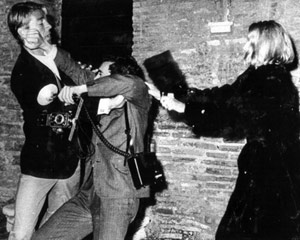

It was during one such radio epic that I was asked by an interviewer what made me want to visit the dark side that is, why write a book about the paparazzi? It is specifically because it is the dark side that I felt it would be interesting to shine some light and see what was revealed. For most of us in the profession of photography the paparazzi are like drunken, philandering uncles that the family refuses to acknowledge, but who mysteriously seem to be making more money than the rest of us. To be a paparazzo you have to be totally insensitive or at the very least tough-skinned, because it's a job that gets no respect not from your subjects, your peers, or even the readers who buy your work in such copious quantities. About the only people who acknowledge your importance are the editors of the ever-increasing number of magazines who rely upon unauthorized celebrity photographs to fill their pages. What this phenomenon says about our society and the implications it holds for our profession seemed worth looking into.

I suppose I shouldn't have been surprised by the extent to which the paparazzi will go to get their pictures, until I found out how much further this goes from merely hiding in bushes. When exclusive pictures of Princess Diana were fetching hundreds of thousands of dollars, όber-paparazzo Phil Ramey once rented a submarine at $16,000 a day to try and get pictures of her sunbathing on exclusive Necker Island in the Caribbean. It wasn't until he was offshore at a depth of 50 feet that he discovered this vessel, being a nautical research tool and not a warship, didn't possess the periscope upon which he was relying to shoot the pictures that would justify the investment.

Another instance of the "whatever it takes" mentality at work was the operation mounted by the National Enquirer to try to cover the wedding of Michael J. Fox to Tracy Pollan in Vermont in 1988. They set up a military-style operations trailer, overflew the site in a helicopter, and discovered that the only way to get close enough to the tent in a field that would house the ceremony and reception was to cross another field in which a herd of llamas were peacefully grazing. Their tranquil existence was soon to be shattered by a group of Enquirer photographers dressed in llama suits provided by the magazine edging toward shooting range. Not only was this one occasion when the paparazzi could justifiably be described as acting like animals, but it was also an example of the best-laid plans of tabloids going awry. At the very last minute, and despite the fact that it was a warm and humid day, the organizers lowered the sides of the tent, thereby thwarting the llama-like shooters.

To be a successful paparazzo you don't have to be a great photographer, even though a couple of them are, Ron Gallella being an example of somebody who would probably have risen to the top of whatever area of photography he devoted his talents to. But for the most part photographic quality is not a prime requirement. A young L.A.-based photographer, Steven Ginsburg, described the relationship between quality and profit in less than flattering terms. "If it was a picture of you, Peter," he proclaimed, "it would have to be sharp and correctly exposed, because you're nobody. But if it was a shot of Tom Cruise and Nicole Kidman getting back together, then a shadow would do."

I was also surprised by the fact that only one major celebrity Susan Sarandon would talk to me on the record about the paparazzi. Either my multiple inquiries were ignored, or I was told, mostly through intermediaries, that the celebrity in question didn't want to antagonize the photographers. This betrays a fundamental misconception that many celebrities have that in some way this is personal; it isn't. The sole motivation that causes the paparazzi to go to the lengths that they do is money it's always the money, whatever any of them say. As long as the celebrity has a dollar sign emblazoned on their backs, that's as long as they will be the focus of the photographers' attention. It may be scant compensation for the almost total loss of privacy, but at least if you're being chased by a pack of scruffy young men with long lenses you know that your career is on track.

The ability to sense who's hot and who's fading is also a skill that they possess, and one of the complaints that you hear from the photographers is that the celebrities court them on the way up, and on the way down, but when they're at the top of their game it's, "What are we going to do about these dreadful people?" Now don't get me wrong, there is no doubt that the paparazzi make life hell for 'A' list personalities, but the relationship between the two is more complex than it initially appears. In the first place these are people who make considerable amounts of money attracting and keeping the public's attention, and it's probably naοve of them to expect that attention to be controllable. Having said that, the best of them are good at manipulating the media.

At the moment we are entranced with Brad Pitt and Angelina Jolie's every move, and it's no coincidence that "Mr. & Mrs. Smith" is about to be released. We are also having to endure the nauseating spectacle of Tom Cruise gushing over the all too cute Katie Holmes, allegedly his latest love. It should be noted that "War of the Worlds," his movie, and "Batman Begins," hers, are about to come out just after this tidal wave of adolescent emotion has engulfed us. Cruise is also somebody that the photographers say is impossible to get unless he has a movie about to be released he simply evaporates between films.

In many ways what we are witnessing here is as much to do with control as it is invasion of privacy. Publicists are willing to provide information to photographers when it suits their client's agenda, and have even gone so far as to set up paparazzi-looking shoots that are then released and controlled by them. What drives the PRs and stars crazy is that they have no control whatsoever over the work of the paps. This is precisely why these photographs are very appealing to magazine editors fed up with jumping through the endless hoops that the publicists put up, often, it seems, just for the fun of seeing editors jump through hoops. In fact, if you discount the hard-core tabloids such as the Enquirer, the photographs that are popular with the mainstream fan mags are innocuous in the extreme.

In many ways I think that this is the secret of our fascination with celebrities. In a society where we increasingly feel anonymous and overlooked they are highly visible and courted; as opposed to our regulated nine-to-five lives theirs are free of restraint from bosses, financial insecurity, and they don't even age like we do. As one agent told me, the subjects of the paparazzi who work with him are all "good-looking, rich and young." They are our fantasy ideal, and the paps make them real.

To me whether the paparazzi are good guys or the other kind is less interesting than why and how they do what they do and why there is a seemingly endless demand for their photographs. Much of what they do I wouldn't even begin to defend especially the very dangerous car chases that routinely occur in Los Angeles, as was recently highlighted by the ramming of Lindsay Lohan's car by a photographer but our society demands their work while routinely rejecting stories on famine and AIDS in Africa, poverty and aging in this country, conflicts around the world and all the other subjects that most of the readers of this publication feel are important. It is important for us as journalists to understand why this is, and not to dismiss it with a vague, but frustrated feeling of superiority. On the other hand, as one of the few people in the world who takes notes while reading "In Touch," I can't wait to get back to a bit of elitism.

© Peter Howe

Executive Editor

|

||||||||||

Back to June 2005 Contents

|

|