|

Going to Court in Iraq

December 2007

|

|

|

Iraq, many people might be surprised to learn, has a functioning court system. Well, "functioning" might be too strong a word but it does have an array of non-religious criminal courts run by the Iraqi government. A few days ago I had the chance to see a small one operate up-close.

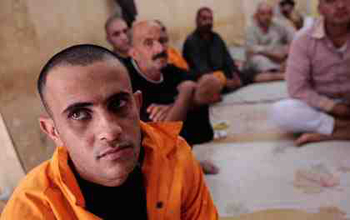

On Nov. 6, 2007, an arrested Iraqi man stands before Iraqi judges in a makeshift courtroom. Around 300 Iraqi men who have been swept up in raids by Iraqi and U.S. forces--often on charges of insurgent activity or organized crime such as kidnapping rings--are detained at a sparse, rudimentary jail on a combined U.S.-Iraqi military base here.

The chance came up suddenly. I was on the ground at an Iraqi-run jail, photographing the conditions there when one of the Iraqi guards called out a series of names. One by one prisoners hopped up from their spots on the floor to assemble in the courtyard outside. An Iraqi translator working with the U.S. Army was with me; he keeps his real name secret like all the Iraqis working for the Americans, though his nickname was emblazoned on his U.S.-style fatigues: Slim. I asked Slim what was going on.

"They are calling them to appear in court," he said.

"Well, I better go with them and see what it's all about," I said after a pause.

"Why not?" Slim said.

Around 300 Iraqi men who have been swept up in raids by Iraqi and U.S. forces are detained at a sparse rudimentary jail on a combined U.S.-Iraqi military base here and about five to 10 a day are outfitted in orange jumpsuits and brought before a panel of judges at a nearby makeshift courtroom.

The 10 or so prisoners all seemed to know what to do: they grabbed orange jumpsuits and blindfolds from a pile in the corner, and started to don them over their clothes. Then they silently lined up for the trip. They were surprisingly docile with the vacant stare of prisoners resigned to their lot.

In Baghdad, Iraqi men who have been chosen to appear before an Iraqi judge to be arraigned put on orange jumpsuits for the trip to the court on Nov. 6.

The prisoners were loaded onto the back of a truck to head to the court building nearby. They removed their blindfolds themselves long enough to scramble down from the truck when they arrived and then put them back on. Each prisoner laid a hand on the one in front and they were led in a long file into the court building.

This court building clearly wasn't designed as such; it was a just simple small structure, the size of a small house. The prisoners were brought into a room in the back and then, one by one, brought into a makeshift courtroom. Two judges, balding men in ties, sat behind small desks with a stack of prisoner dossiers by their elbows. A middle-aged woman in black sat intermittently in a chair across from them; she, it turns out, was an Iraqi lawyer and acted as a sort of public defender. A TV was on in the corner quietly playing Lebanese music videos.

The men who've been chosen to appear before an Iraqi judge to be arraigned are led in, blindfolded, to the court building in Baghdad on Nov. 6.

A prisoner was brought in before the judges; I asked Slim to translate what was going on.

"The judge is telling him that he is accused of being in a kidnapping ring," he said.

"What is the prisoner saying?" The young man in orange was rambling in Arabic and gesturing wildly.

"He says, 'No, I am not.'"

"That's all he's saying? Look, he's still talking."

Slim cocked his head toward the prisoner.

"Okay, he's saying: 'No, I don't know any kidnappers, I am innocent, I just own a simple shop in Ameriyah,' things like that."

The judge nodded, took a few notes, and then sent the prisoner off. Once he left I talked to the judge.

"So the guy says he's innocent?" I asked.

"Yes, he says he is not a kidnapper," the judge said, still writing. "Maybe yes, maybe no."

"How many people admit to guilt here? Does anyone come here and say 'Yes, I did what you say'?"

The judge thought a few seconds. "It happens sometimes. Maybe five percent of the time."

"What's going to happen to this guy?"

"He will go back to jail until he has a trial."

"When will that be?"

The judge smiled. "Oh, I don't know. Sometime."

On Nov. 6, Iraqi men in a police detention center wait to hear their name called to appear before an Iraqi judge.

Each of the prisoners was seen in this way, most of them accused of either kidnapping-related crimes or of insurgent activity. One was allegedly found with a bomb in his trunk; he was the most quiet. Most of the others animatedly engaged the judges--some of the prisoners seemed relaxed and smiled a lot, like they were giving a sales pitch.

By lunchtime all the hearings were finished and I headed back to the U.S. portion of the base which was so close I walked. I wasn't sure if what I'd just seen was an example of justice or a perversion of it. I'm still not sure. Like any photographer I strive to get to the center of what's happening, but sometimes even when you get there it's difficult to ascertain the truth behind what you see--especially in Iraq.

Chris Hondros was born in New York City to immigrant Greek and German parents. After receiving a degree in English Literature at North Carolina State University in 1993 and conducting his graduate work in photojournalism at Ohio University's School of Visual Communications, Hondros returned to New York to concentrate on international reporting. He has photographed in most of the world's major conflict zones since the late 1990s, including Kosovo, Angola, Sierra Leone, Afghanistan, Kashmir, the West Bank, Iraq, and Liberia. His images have received dozens of awards. In 2004 Hondros was a Nominated Finalist for the Pulitzer Prize in Spot News Photography for his work in Liberia and in 2006 he was awarded the Robert Capa Gold Medal, war photography's highest honor, for "exceptional courage and enterprise' in his work from Iraq. He lives in New York City where he is a staff photographer for Getty Images.

Click the following links to read some of his previous DJ Dispatches: • http://digitaljournalist.org/issue0511/dis_hondros.html • http://digitaljournalist.org/issue0505/dis_hondros.html • http://digitaljournalist.org/issue0502/dis_hondros.html

© Chris Hondros

|

|

Back to December 2007 Contents

|

|