Seamus Murphy describes photography as "part history and part magic." This brief description could be a title for Murphy's entire archive, as he is the embodiment of the soulful photojournalist. A native of Ireland, he has worked extensively in the Middle East, Europe, Russia and the Far East, Africa, North and South America, and has to date won six World Press Awards. Murphy's work spans years and continents, but we have chosen to concentrate on the area that captivated him perhaps the most in recent years—Afghanistan. His recent book, "A Darkness Visible," published in 2008 by Saqi Books of London, is a retrospective of his work in that country since 1994.

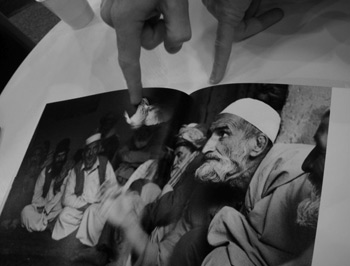

Murphy's mesmerizing collection of black-and-white photographs tells the story of the Afghan people who, enduring a perpetual state of devastation, still maintain a vibrant culture. It also reveals a gifted journalist with the heart of an artist, compelled to undertake an epic project in a country entirely unlike his own. With each return Murphy seems to have become even more deeply involved with the fluctuating reality of the Afghan land and its inhabitants.

Murphy's mesmerizing collection of black-and-white photographs tells the story of the Afghan people who, enduring a perpetual state of devastation, still maintain a vibrant culture. It also reveals a gifted journalist with the heart of an artist, compelled to undertake an epic project in a country entirely unlike his own. With each return Murphy seems to have become even more deeply involved with the fluctuating reality of the Afghan land and its inhabitants.

In his afterword for "A Darkness Visible," Murphy describes himself and other photographers as "thieves who sometimes rob but don't pay back," though "by necessity." However, his images speak volumes to the contrary. This remarkable photographer consistently gives warmly and wholeheartedly to his subjects, and his images display a bond rarely achieved even by the most ethnographically talented and artistic observers.

I met Murphy in Perpignan, France, last year at Visa Pour l'Image while he was informally presenting his just-released book to a magazine photo editor. From the moment he began turning the pages I was deeply drawn to the photos and couldn't help wanting to know more. Every image had a story, and his anecdotes about each one were just as fascinating as the images themselves. The book for me became a must-have, and I went immediately to the bookstore in Perpignan and bought a copy of my own.

Maybe it's the mysteriousness of black and white that makes the Afghan darkness literally and metaphorically visible in the images, but I think the soulfulness emanates from the photographer himself. How Murphy does this is not easy to explain, so I think the best we can do is look at the images, listen to what he has to say, and let our hearts and minds do the rest.

Maybe it's the mysteriousness of black and white that makes the Afghan darkness literally and metaphorically visible in the images, but I think the soulfulness emanates from the photographer himself. How Murphy does this is not easy to explain, so I think the best we can do is look at the images, listen to what he has to say, and let our hearts and minds do the rest.

In the book, complementary essays by Nancy Hatch Dupree and Anthony Loyd serve as verbal bookends to Murphy's 13-year photographic exposition. The images are each captioned briefly, belying what could surely be a stand-alone, multiple series of essays. My only criticism of the book were I to have one—and I don't—would be that the reader cannot know the wonderful back stories to the photographs as told to me in Perpignan.

Recently, I had a chance to ask Murphy a few questions about the developmental path of his career that now includes work on every continent, and we focused in particular on his intense, abiding interest in Afghanistan. His response follows, in his own words, and gives a hint of why he opens his book with an inscription from the tomb of Mughal Emperor Babur (1483-1530), who conquered Kabul in 1504 and is buried there:

"If there is a Paradise on earth, it is this, it is this, it is this."

As a young Irish boy in 1963, Murphy saw U.S. President John F. Kennedy in Dublin. Working as a photojournalist years later, he saw America through a different lens, but he says a fire was lit that day in 1963 that has never extinguished—a fire that "promised an infinity of dreams." I wondered if seeing JFK was the beginning of his involvement with photography, but it turns out it was the beginning of something else, very much inspired and shaped by the idea of America and all that it stood for at the time.

I was 4 when I saw JFK in Dublin; it's one of my earliest memories, and I didn't get around to photography till my late 20s ... late starter. My father swore he would never visit America after they killed Kennedy. It has to be said he had a fear of flying too.

No matter what anyone tells you, America had and still has an enormous impact on us non-Americans. We saw it as the other place, the other side, the refuge, and to hell with tradition. The place where fun wasn't an 'F' word, where they had the wit, balls, money and foolishness to make "The Beverly Hillbillies" and "Get Smart." I am still a devoted disciple of the gospel according to Sergeant Bilko.

Knowing now that it's so much more complicated than it seemed to a pre-teenager—of course, it was about coinciding with the emergence of teenage spending, that fun comes at a price and that it wasn't all fun for the Americans themselves—doesn't take away its appeal, glamour and the promise of the possible. To a kid, it was a bit like going to the adult who was more likely to say 'yes' as opposed to one who always said 'no.'

Knowing now that it's so much more complicated than it seemed to a pre-teenager—of course, it was about coinciding with the emergence of teenage spending, that fun comes at a price and that it wasn't all fun for the Americans themselves—doesn't take away its appeal, glamour and the promise of the possible. To a kid, it was a bit like going to the adult who was more likely to say 'yes' as opposed to one who always said 'no.'

None of this I really thought too much about until after I made some road trips in America in 2005 and 2006, when I started jotting down some ideas about what I was doing, what and why I was taking on by photographing this beast, and remembered a pretty significant event in my life, that time had misplaced.

On childhood, the emergence of social and political consciousness, and his interest in photography:

I was actually born in England, was the youngest of six kids and was 6 months old when my family returned to live in Ireland, having lived in England. This would occasionally cause situations in the classroom when I was asked where I was born. I grew up in Taliban Ireland—the Irish Catholic chapter. The country was in its infancy as a republic and there was a fair amount of fundamentalism around. The Catholic Church had a nasty amount of power (yet more revelations recently about clergy and sex abuse), which was unhealthily linked to Irish Republicanism and the throwing off of the yoke of British Empire. This gave corrupt politicians license to destroy swathes of Georgian Dublin in money-grabbing property swindles—all in the name of ridding Ireland of the filthy, ungodly British presence.

I was 8 when the 'Troubles' started up again in Northern Ireland. When the Catholics were being burned out of their homes, neighbours were talking of driving across the border with guns. I am sure it was all talk but those were the times.

When I was 11 we had the backlash with bomb attacks in Dublin from Protestant paramilitaries. So this was all exciting stuff and not something we were used to in sleepy Dublin. In some way, it introduced me to the idea of news, politics, change and violence. Had I been more attuned I would have also seen the links with the civil rights movement in America. But I think it pricked an interest that stays with me to this day about current events and the course of history—and a curiosity about where beliefs and actions come from, and trying to capture the passion and consequences of what follows.

Photography as a medium and as something that I would personally develop wouldn't come till much later. It was when I lived in San Francisco after college in Dublin—I started photographing and using a darkroom, and it was the darkroom that lit the fuse for me. So from the start there was a connection between black and white and being able to control my work. Of course, now we can scan or shoot digital and we control all that—but for me, at that moment this is how it happened. And there were these great yard and garage sales and people seemed to have endless supplies of amazing photography books that they were selling—maybe it was people splitting up and burying the past, God knows, but I devoured these, at $1 or $2 a go.

On beginning his work in Afghanistan:

Why Afghanistan? I was sent there on assignment in 1994. Actually 'sent' is misleading. I pitched, along with a writer friend, the idea of going to Afghanistan to the Observer newspaper here in London and they agreed. It was a forgotten war and yet I read at the time that more people were being killed and dying there than anywhere else in the world. It was incredibly difficult to get there and the only way to handle logistics was through an NGO—we had an arrangement with CARE International.

Kabul was under siege; there was a perilous journey one took by road from Peshawar through a load of dodgy stoned checkpoints, but I will never forget arriving the following day on the outskirts of Kabul and driving through a city that was like something out of 'Mad Max.' People were scurrying around in fast-forward, trying to scrape a living—before the next round of bombings, shellings or fighting. It was a baptism of fire for me and I learned an awful lot in that month-long trip.

Two years later in February 1996, I was back—the Taliban had just taken Herat and were beginning to be taken very seriously. I went on assignment with writer Anthony Loyd, whom I met for the first time at the airport, and whom I subsequently have worked with a lot in Afghanistan and elsewhere, who wrote the afterword in my book, and is a great mate. When the Taliban took Kabul in October 1996, we returned again and, I guess, so started the involvement with Afghanistan.

Over the last 15 years Murphy has done many projects elsewhere in the world, but says he misses Afghanistan when he is gone too long. I asked him if he was surprised at his attachment to something so different, so foreign from his native Ireland, and to what did he attribute such a deep connection to the country and its people.

I am not at all surprised in becoming attached to Afghanistan because it never seemed foreign. I think it's being Irish—we are great travellers, and great mixers. We have had to be, historically—to survive—and under British rule it was the only way to get peace and respect. You can't go anywhere in the world—and I mean anywhere—and not find a Paddy that hasn't been there before you, who has already charmed or robbed everybody in town. And I have to say the Afghans have a very similar attitude towards life as the Irish. Like the Irish, they are respectful but irreverent and talk horribly behind your back. They love a laugh and a tune and they aren't afraid of poetry. Afghans are especially like people from the west of Ireland, regarding connections with the ancient.

Murphy's account of the conflict in Afghanistan is very personal, very focused on the human element rather than the fancy machinery of war. Represented by the agency VII, he prefers to work independently rather than embedded, as has become standard for most photographers since 2003. I asked him about the logistics of getting around.

My preferred method of getting around in Afghanistan is in a little car—the ubiquitous Corolla—that passes as local, and very often is. Anything bigger and involving more people gets in the way of the work and draws too much attention. For example, I worked this way in Badakshan, Balkh, Kandahar and Nangrahar over two trips in 2004, against official advice, and survived. Of course, situations change with time and wouldn't include places like Helmand where it's necessary to be protected or embedded.

But on this last trip to Afghanistan in May and June 2009 I was being told not to move freely in Kabul, let alone the Shamali Plain and Nangrahar, which would be seen as too risky and where I very comfortably spent some nights in villages, so paranoia plays its part. Also, if you work for an organization it's easy to become institutionalized by their rules—I guess you have little choice—which is a shame because people are missing the best part of visiting Afghanistan, which is hanging out with Afghans.

The photographs in "A Darkness Visible" are published exclusively in black and white, but most of Murphy's work elsewhere is in color. I asked him about his predominant use of black and white vs. color in Afghanistan.

Why black and white? It seemed to suit the mood and emotion of the times I was experiencing; it certainly matched my feelings … it felt right to record what I was seeing in black and white. These were epic times and despite the apparent lightness of the people, it was also a dark time of great extremes. I was shooting colour throughout—in fact two assignments in 1996 were in colour and published as such—but it's the black and white that I was also shooting that seemed the more eloquent.

It was probably also an extension of my roots in photography—I really had been shooting professionally for about five years in 1994 and I felt I could say it better in black and white. At the time I remember observing that I never regretted shooting a story in black and white but that I did sometimes resent being forced to shoot something in colour by a magazine. It became a default position, which with so many other things to concern you as a photographer, this was something I didn't have to think about.

That pretty much all changed when I started to shoot my next big project in 2005—and which I am still shooting: America. I started out with colour and black and white, but after a few days I knew this was going to have to be colour. Edward Hopper was what I had in mind. And it would be on film. There weren't any deadlines and I didn't want to be downloading and editing in the nights when I could be out shooting or exploring. I also prefer the colour film look.

I have just returned from three weeks in Afghanistan and I have been shooting colour, but with some black and white. The black and white is the continuation of a project I have been shooting on one family I met and stayed with in 1994. This will be featured in a multimedia Afghanistan special for GlobalPost that publishes August 10th.

To get back to colour … I felt it now suited my mood, in Afghanistan. Whatever mistakes have been made by the West since 2001 and the re-engagement in the country post 9/11—nothing will match the bleakness I saw in 1994, 1996 and 2000. The West had turned its back and abandoned the Afghans, and we all know where that led.

In the end, it's all photography—black and white or colour, film or digital. And if you get to choose which, that's good; it's personal. I have to laugh at those who say that one is better than the other, like one is truer, more ethical—makes you a better person. Every period throws up its dogmas, which is usually more about self-promotion and vanity. The real question—is it honest, is it original, does it try to be original, is it any good? That's the real question.

After listening to Murphy’s radio interview and knowing there are so many stories over 15 years' time from Afghanistan, it surprised me that he didn’t write a lengthy essay himself, rather just a short afterword and acknowledgement. I asked him if the silence was deliberate to favor the visual, and if he feels his essential message is being communicated.

I really don't have a message—I am probably as much in search of answers. What drives me is to shoot what interests me and to find out how life is for all of us. In that there may well be messages of humanism and my belief in the ultimate goodness of the vast majority of people—but it is not a conscious subtext.

I did write something about thanking the Mujahedeen fighters who stole my broken Leica but mercifully discarded a plastic bag with the rolls of film that I had shot over months in the run-up to the fall of Kabul. It was tucked away in the Thank-You's page at the back so I take your point.

The experience of putting the book together took enormous energy and attention to get the book to press, albeit a year late. I did feel that so much had gone into the imagery—not just the photography but also the edit and sequencing—that it was the time to let the pictures speak for themselves. It was time they earned their keep.

And I was conscious too that I had two amazing writers—Anthony Loyd and Nancy Hatch Dupree. Anthony is unequalled in articulating his thoughts with sincerity and emotion and Nancy Hatch Dupree is a legend when it comes to Afghanistan, and as well as being an expert on the history of the place, she crucially knew it in happier times. I couldn't have had a better combination and I love both pieces.

The Digital Journalist proudly presents a gallery of Murphy's photographs from "A Darkness Visible" courtesy of the photographer and VII Network.

Beverly Spicer is a writer, photojournalist, and cartoonist, who faithfully chronicled The International Photo Congresses in Rockport, Maine, from 1987 to 1991. Her book, THE KA'BAH: RHYTHMS OF CULTURE, FAITH AND PHYSIOLOGY, was published in 2003 by University Press of America. She lives in Austin.