|

|

An Appreciation of

Carl Mydans

by Marianne Fulton

|

|

History!

Carl Mydans is a great photographer.

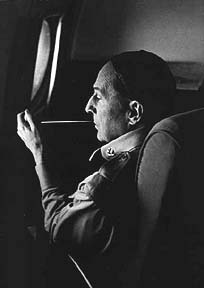

Looking at his famous photographs of General Douglas MacArthur, listening

to Mydans talk about the camaraderie at LIFE, and reading his books, one

gains an appreciation for his vision, for the intelligence and sensitivity

that made him want to be part of the historical moment. This is not

just an appreciation of a photographer's pictures but of his humanity at

work in the twentieth century.

Mydans has said that he has always been a people-watcher, looking at posture

and the telling gesture which might reveal something of the person. He

would watch mouths and look for falseness. As he began to understand this

unspoken language and interpret what he was so carefully observing he wrote,

"I had found a source of stories as wide and as varied and as captivating

as the human race."

Mydans has said that he has always been a people-watcher, looking at posture

and the telling gesture which might reveal something of the person. He

would watch mouths and look for falseness. As he began to understand this

unspoken language and interpret what he was so carefully observing he wrote,

"I had found a source of stories as wide and as varied and as captivating

as the human race."

As important, Mydans has a sense of history, and seemed to understand from

the beginning that his photographs were small emblems of contemporary history,

happening on the streets and in the war zones. Through accumulation, these

moments would meld together into a sense of a particular time and place.

Ironically, great war photographs seldom, if ever, show two sides battling

hand-to-hand to the finish. Distance is a secret presence and obstacle

in this genre of work. How does one impart an emotional understanding

of the larger situation, let alone tell a balanced story from only one

side within a constricted environment? One looks at incidents, individuals,

gestures, at the very things Mydans had trained himself to do when he perfected

his craft while working for Roy Stryker in the Farm Security Administration.

Perhaps his intuitive gift of empathy in the narrative unfolding before

him has been his greatest gift to the field.

If you think Mydans does not know what he's seeing or stands apart from

its impact, read his 1959 book More that Meets the Eye. It is one

of the most moving, beautiful photographic books produced in any decade.

Yet, there are no photographic reproductions in it. Instead, the

gut-level sense of the small moment symbolizing a larger conflict is related

time and again within the text. It is more than meets the eye - it

is the interior vision, the haunting memory, the shared agony of a man

in the midst of a world beyond his control. A philosopher once wrote

that one knew the quality of a person's mind through their writing. In

Mydans' first book, one also understands the quality and sources of one

man's vision. Not only through his intellect - his sense of purpose

- but also through an outpouring of feeling.

In literature, as in photography, the descriptive moment is yanked out

of the flow of events and held up for all to see. Done correctly, it has

a memorable impact. For example, in More Than Meets The Eye, there

is a story set during the Korean War of a Turkish doctor working in freezing

temperatures confronted with yet another dying man . Mydans sets

the scene:

"Late one afternoon in 1951, as the sun jumped behind the snow-covered

ridges of the Korean mountains, turning the top slush into crystals, a

Turkish patrol, shouting incom-prehensible words of recognition, struggled

back into their lines. They half-carried, half-dragged a poncho in

which quivered an incredible bundle. They moved in miniature through my

camera finder, hunched, silhouetted figures against the failing light."

Going into the tent with these cold men and there strange cargo, Mydans

watches the Turkish doctor pull back the edge of the poncho and peer inside.

There is a mound swaddled in roughly-made emergency bandages. Mydans continues,

"Two holes at the top showed black, glazed eyes. 'Turkish soldier,' said

the medic as he stood half-crouched beside me with a pair of scissors in

his hand. He struggled for his English. 'Turkish soldier,' he repeated.

And then angrily he pantomimed the scratching of a match and the torture

of fire.

As the bundle was slipped onto a litter and carried away to an ambulance

the doctor rose and faced the mountains. Pointing toward the darkening

horizon, he turned and shouted, 'History!' In exasperation he searched

for other English words, but they would not come. 'History,' he shouted

again and then stood jerking his fist into the air, looking wordlessly

toward the purple twilight."

This is the first page of the book. On the last, Mydans writes, "The sense

of history and drama comes to a man not because of who he is or what he

does but flickeringly, as he is caught up in events, as his personality

reacts, as he sees for a moment his place in the great flowing river of

time and humanity."

This is not supposed to be a book review, but just shy of 40 years later,

the verbal images Mydans creates are as moving as those he made with a

camera.

Let's look at two images of women: In "French woman accused of sleeping

with Germans during the occupation is shaved by vindictive neighbors in

a village near Marseilles," we see a woman being ridiculed by people on

the street. There is no place to run or any purpose in resistance.

She does not look rich, she wears a simple home-made blouse with rick-rack

sewn on for meager ornament. The composition of arms, eyes, the v-shaped

line of her accusers' heads, and the backlight of bright leafy summer lead

repeatedly to her closed eyes. We are very close. Was she the only collaborator

in the crowd? The taunting laughter from two onlookers and the sly glance

towards the camera by the man on the left make an uneasy moment with no

answers, only questions.

It is a caught moment, but interpreted photographically for maximum strength.

That is what sets Mydans apart from other photographers. It reiterates

his command of telling gesture and powerful arrangement.

Another woman, "A Korean mother carrying her baby and her worldly goods

flees the fighting around Seoul in the winter attack on the Korean capital

in 1951." For me, the sculptural quality of this image makes it one of

the most beautiful Mydans took during the war years.

As a curator, for me to call a war image "beautiful" reminds me of photographers

like Larry Burrows and Don McCullin who have agonized whether they were

somehow benefiting from the misery of those they photographed. I

have always admired Mary Ellen Mark's no nonsense reply to similar questions:

"Would you rather I did not take the photograph?" Meaning , in part, is

it easier for you not to look, not to know?

This photograph is exceptional. A young woman holding a precarious load

on her head, moving onward, suckles an infant bound to her body securely

in cloth, in the traditional fashion, while intensely concentrating - on

her steps? She cannot afford to fall. Or, lose her precious baggage. (Remember,

the caption states that there is fighting and an attack going on.)

She is the central subject of the image where everything is circular, antiquely

feminine, primordially important. She must make it. Besides showing a refugee,

this is about motherhood, about the human race.

There is another woman not often pictured in the gathering of Mydans' greatest

pictures. But, she is there, if only in his mind. It is Shelley

Smith Mydans. We see her in the early book at LIFE working late at night,

inundated with paperwork; Carl stops and asks what she is doing with all

these mathematical figures on scraps of paper. She replies that she is

balancing the budget - the national budget - for an article. Another insatiably

curious perfectionist, how could he not love her?

One of the great tributes to his wife and partner corespondent for LIFE

magazine, is found in More Than Meets the Eye. Mydans leaves alone

on another war assignment, leaving Shelley behind at Penn Station for the

first time. Contemplating the figure growing smaller on the platform,

he admits that he was still not completely sure of himself after the horror

of their shared Philippine imprisonment by the Japanese. He writes,

"And that night as I headed back to another front in another land, I was

suddenly aware that so much of the strength I had always thought was mine,

was Shelley's."

Carl Mydans is one of our best photographers. He has been everywhere.

For many years he worked under siege. He was not deterred from his vision

nor his obligation to tell the story. He was obsessive about keeping

notebooks containing captions and background material. Whenever humanly

possible he developed his film every night in various dark bathrooms across

the world so that LIFE would receive the story on time.

In the Pensées, the French philosopher Pascal observed that "the

greater the intellect one has, the more originality one finds in men. Ordinary

persons find no difference between men." Mydans has always seen the

uniqueness of each person. Look at his photographs.

- Marianne Fulton is the Chief Curator

at the George Eastman House in Rochester, New York, and a leading author

and authority on the history of photojournalism. |