|

by Don North The Internet has brought a new dimension to the job of war correspondent and has stepped up the pace of conflict reporting. It used to be that warriors on both sides of a conflict, from the grunts to the generals, all put their case through the war correspondent. Information and disinformation went through the filter of an experienced journalist, trained in sifting through conflicting viewpoints to focus on the most important news their readers should know about a conflict. Kosovo may be the first major international dispute where the battle for hearts and minds, always an important adjunct to a shooting war, has shifted to the Internet. The combatants are often bypassing the ladies and gentlemen of the press to communicate their viewpoints directly to the public through their web sites. In Kosovo, the policymakers who used to brush off journalists with, "no comment", now say, "check my web site." There are at least fifty web sites with a point of view on Kosovo that anyone with an Internet connection can access.

Kosovo on the Internet points to new battles between the media and the military in future conflict. Barrie Dunsmore a former ABC News war correspondent and author of "The Next War: Live!" for Harvard's John F. Kennedy School of Government sees Kosovo as a harbinger of new consequences journalists may face covering international conflict. "Kosovo is the first glimpse of the Internet's impact in wartime. In a larger war, US Military sources at the highest level tell me they are prepared to jam Internet connections or even shoot satellites out of the sky if they feel security of military operations may be threatened. Scrambling and manipulating journalists Internet communications are also options under active consideration to spread disinformation in support of military operations."

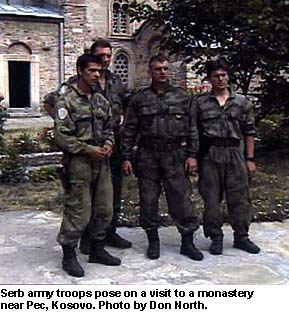

Kosovo is about the size of Connecticut with a population of only two million. Although journalists keep reminding their editors that this conflict could spill over into neighboring Macedonia and Albania, as well as Turkey and Greece, Kosovo rarely makes page one, and that suits Belgrade's dictator Slobodan Milosevic just fine. If he learned one thing from the war in Bosnia, it is to keep images of burning homes and suffering refugees off the world's television screens and newspaper front pages. For a page 12 newspaper story or a thirty second blurb on the Evening News, it's a tough story for a journalist to get a handle on. Until NATO negotiated a pullback in late October, Serb police and Army checkpoints were encountered every few miles along major highways. If an attack on a village was underway, journalists and observers were not allowed through. You must take to the side roads or dirt trails to find other ways into an area of conflict. It also meant risking roads that could be mined by either side. For a few seconds of distant smoke from burning homes, the television crews, photographers and reporters often risked their lives. On the way to my assignment in Kosovo, driving south from Belgrade, I passed through the Serb city of Nis. At the Church of St. Nicholas, converted from a Mosque, stands the infamous "Skull Tower", a fitting tribute to the Balkan tradition of being bestial to your vanquished foe. Following the Battle of Cegar in 1809, the Turkish victor Hurshid Pasha built a tower. Into the wet cement he sealed 952 severed heads of Christian Serb enemies. Today 60 skulls can still be seen, grinning sardonically through the ages. In the long history of mans inhumanity to man, the never ending Balkan wars started a tradition that killing your enemy isn't enough, they must also be mutilated and stripped of any dignity in the eyes of those who loved them and claim the remains. There have been a few refinements since Hurshid Pasha denied a decent burial to the Serb warriors. Now the display of inhumanity in Kosovo has largely been assigned to the Internet. Albanians frequently lead journalists to the bloody sites where whole families and villages have been murdered and mutilated by suspected Serb police actions. In Gornje Obrinje, September 29th, 21 Albanians from one family clan were brutally executed, following the ambush of seven policemen near the village. Grissly photos of the bloody victims, some of them babies in their mothers arms, appeared on the Albanian daily Kohe Detore web site within hours of the crime. They were photos so gruesome they would not appear in any major newspaper.

Both sides vigorously deny the atrocities. Serb police often blame the guerrillas for civilian atrocities. In defense, KLA spokesman Adem Demaci recently said, "the KLA is by its very nature and philosophy incapable of crimes against civilians." There is little doubt that rogue elements on both sides have committed crimes against Serb and Albanian civilians. United Nations Secretary General Kofi Annan, reported both sides are to blame, but that the majority of crimes had been committed by the Serb military. The brutal publication of their crimes on the World Wide Web just hours after the act may have more clearly defined the war crimes of Kosovo than in any other conflict. But Internet or not, in the October agreements that held back NATO bombing, Belgrade refused to accept the jurisdiction of the Hague War Crimes Tribunal or allow their investigators to visit Kosovo. If the ancient warriors like Hurshid Pasha had been brought before an international war crimes court for the desecration of his enemies heads in the Skull Tower, perhaps the spiral of vengeance and "eye for an eye" cruelty would have been curbed. Perhaps not. Until the recent Hague Tribunal on Bosnia war crimes, atrocities have remained largely unpunished in the Balkans, and terror-as-theater to intimidate survivors has become a tradition. If there is any doubt the Internet has excellerated the pace of war coverage, try filing a questionable story. Chances are, like Erich Rathfelder of the German Tageszeitung, you will be escorted to the border before the ink is dry on your story. On August 5th, Rathfelder reported "hundreds of civilians" were dumped on a pile of garbage at the edge of Orahovac. An unnamed Gypsy witness was quoted saying he helped bury 567 bodies. Reporter Rathfelder described "dozens" of mounds of freshly dug graves. Tageszeitung implied it was the Kosovo equivalent of "Serbrenica." Within hours of the stories release through the Internet, a majority of the 100 diplomatic observers and 300 accredited journalists in Kosovo were on their way to Orahovac. Many of them found the Gypsy quoted by Rathfelder and declared him unreliable as he changed details of his account with every telling. Serb officials rushed their own explanation onto the Internet. The gravesites, they said, contained bodies of about 40 KLA "terrorists" killed in the battle for Orahovac. The town cemetery was already full so the bodies were buried just outside of it. Rathfelders scoop was quickly spiked within days. In pre-Internet days it would have inflamed already raw emotions on both sides for weeks before being exposed as bad reporting.

The Serbian Government recently established a comfortable Media Center in the Prestina Grand Hotel. There's a well stocked bar, CNN from satellite, phones and Fax lines, translations of the local press, and for ten Deutchmarks you can get on the internet for an hour. For the Serb side of the war go to http://www.mediacentar.org. In wars gone by, competing news agencies would go to great lengths to keep track of their rivals. Today, there is no more peeking over shoulders in the line at the Cable office to crib from your rivals copy. Now just punch up "Yahoo" or another search engine and Reuters can read the AP file, and the Washington Post reporter reads what the New York Times is printing within hours of the story being sent. At the Serb Prestina Media Center each morning, all major news agency stories on Kosovo are found on the web and copied. To their credit, even the stories unfavorable to the Serb government are distributed. With war on the Internet, scoops from the front lines don't remain exclusive for long. A few blocks away is the rival Kosovo Press Center run by Albanian leader Ibrahim Rugova and his party the Democratic League of Kosovo (LDK). There too you can read a daily flow of press releases and tap into their web site. But questioning Rugova is more difficult. Wearing his signature dark silk scarf, he often appears at the press conference on Friday mornings, but usually rushes off declining interviews. Rugova is one of the most puzzling and mysterious leaders in Europe today. He's a longstanding pacifist and does not condone the guerilla war in which many of his former followers are now engaged. Perhaps more influential and better at Cyberwar than Rugovas organization is the Prestina daily Koha Ditore. (http://www.koha.net) It's a paper that editorially supports Kosovo independence, but covers all sides of the conflict. Koha Ditore's web site and offices have become a first stop in Prestina for both journalists and diplomats trying to sort through the confusion. Editor Dukagjin Gurani says the press in Yugoslavia never had a tradition of presenting facts, only viewpoints. "Now people in Kosovo say our paper is not patriotic because we are objective. At Koha Ditore we feel that the highest form of patriotism is objectivity." Koha Ditore has a vast network of stringers throughout Kosovo who report Serb military movements and detailed accounts of actions by either side. Within hours these details are reported on the Koha Ditore Web site. It is hard to imagine the 2,000 foreign observers who are to roam Kosovo under the NATO agreement being able to track the conflict any better or faster than Koha Ditore's web site. However, the most important source of journalism throughout the former Yugoslavia may well be the independent Belgrade based radio news organization B-92. When Milosevic pulled the plug on B-92's broadcasts during the 1996 student demonstrations in Belgrade, B-92 took to the Internet. Although their broadcasts were returned to the air, a digital seed had been planted and now the Internet is the core of their news gathering activities. B-92's twice daily news reports on the web is the most complete and objective reporting I have seen on the Kosovo conflict and often days ahead of the AP, Reuters or the BBC. Go to etodrazb92e@brazil.tcimet.net to subscribe. During the recent showdown with NATO, Slobodan Milosevic and his henchmen cracked down even harder on the Serbian independents like B-92. Two of the largest Belgrade dailies Dnevni Telegraf and Danas were raided by police and shut down. Their crime, "unpatriotic behavior." Earlier the police shut down several radio stations and banned re-broadcast of Voice of America and BBC. Not satisfied with his complete control over Serbian State Television, Milosevic is using the Kosovo conflict to stifle even the limited freedom that the independent media has in Serbia. Serbian Information Minister Aleksandar Vucic (e-mail is mirs@srbija-info.yu) has also added the Internet to the draconian new Serbian Law on Information passed by the Legislature in October. Minister Vucic specified that a web presentation of publications which commit "verbal or opinion deceit" would be fined between10,000 and 80,000 US dollars. Attacking freedom of the Internet in Yugoslavia may prove a slippery slope for Milosevic and his henchmen. On October 19th the Belgrade magazine Evropljannin (European) was banned for printing a scathing, article headlined "What's next, Milosevic?" Within hours the offending column was picked up by computers behind the walls of Visoki Decani Monastery and blasted out to a worldwide audience on the Internet.

At the high point of combat around Decani last May, as his brothers raised the volume of chanting to overcome the sound of automatic weapons fire outside, Father Sava started bombarding the internet with e-mails to journalists, politicians and diplomats calling for peace between Serbs and Albanians. "Slobodan Milosovic is playing a wicked game with the emotions of Serbs in Kosovo," says Father Sava. "In 21st Century Europe there is no place for ethnically cleansed territories, terror or crimes. The Holy Scripture teaches us that one cannot love God without first loving one's neighbor." He predicts that unless a peaceful compromise can be reached soon, the small minority of Serbs in Kosovo will pay the price for Belgrade's behavior. Father Sava is a thoroughly modern monk. Rising at around 1:00 A.M. to take advantage of the best internet connections, he prays and then surfs the Internet. He will mark stories from a wide variety of sources and then fire them off to be shared with his list of more than 300 reporters, diplomats and friends; this scribe included. The monastery at Decani, on the Bistrica river, near the Albanian border, is the largest in Kosovo, home to 23 monks and an island of spirituality in the sea of war and hate. The Decani Monastery has been nominated for UNESCO's world heritage list. Six hundred years ago dozens of renowned painters were commissioned to create thousands of images on the walls of the monastery's church. Many of the most beautiful illustrate the life of Christ before his crucifixion. One of the paintings even depicts Christ in a spacecraft, an image that drew the attention of Erich Von Deniken, the researcher of lost civilizations. "It's nice to live in a medieval setting as we monks do, but that does not mean we are prepared to accept a medieval mentality. The Internet enables me to speak from the pulpit of my keyboard," says Father Sava. "I'm on a war footing, this is not a normal routine. I usually get 50 e-mails a day, but during the threat of NATO air strikes, there were about 200 a day. People were concerned about us." Father Sava's website is http://www.decani.yunet.com. Slobodan Milosevic may have kept many war correspondents and the tv cameras away from seeing the Kosovo conflict at first hand, but he hasn't stopped the flow of news, images of war crimes or the exchange of ideas between the warring factions from multiplying themselves on the World Wide Web. Kosovo may be the first major conflict being fought out on the Internet. It has quickened the pace of war coverage and put an avalanche of facts, opinions, propaganda and lies in the laptop of the war correspondent. There may be a greater flow of information direct to the public, but the Internet has not replaced intrepid correspondents like The Washington Post's R. Jeffrey Smith, The New York Times' Mike O'Conner, AP's George Jahn or Reuters Kurt Schork to name only a few regularly covering Kosovo. Although greatly aided by the Internet, these correspondents must still decide what's relevant and what is not. For the best war correspondents, the Internet has not replaced the often deadly necessity of commuting to the Kosovo killing fields through the checkpoints and mined roads to check out a story they first saw on the Internet. |

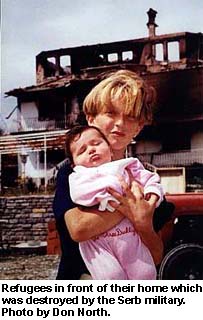

For

the past six months, clashes between the Albanian guerrillas, known as

the KLA (Kosovo Liberation Army) and Serb police and Army units have created

a massive refugee problem with about a quarter of a million ethnic Albanians

fleeing to save their lives. It's as nasty and tragic a little conflict

as I have covered, and I have covered 14 wars, revolutions and assorted

uprisings since reporting the war in Vietnam for ABC News in the 1960's.

For

the past six months, clashes between the Albanian guerrillas, known as

the KLA (Kosovo Liberation Army) and Serb police and Army units have created

a massive refugee problem with about a quarter of a million ethnic Albanians

fleeing to save their lives. It's as nasty and tragic a little conflict

as I have covered, and I have covered 14 wars, revolutions and assorted

uprisings since reporting the war in Vietnam for ABC News in the 1960's.

When

Serbs were the apparent victims, the Prestina Media Center, run by the

Serbs, quickly arranged transportation to a captured KLA base in Klecka.

On August 30, journalists were shown the charred remains of 22 Serbs, including

women and children allegedly tortured and shot by a KLA firing squad and

their bodies burned in a kiln. The photos were on the web site the same

day.

When

Serbs were the apparent victims, the Prestina Media Center, run by the

Serbs, quickly arranged transportation to a captured KLA base in Klecka.

On August 30, journalists were shown the charred remains of 22 Serbs, including

women and children allegedly tortured and shot by a KLA firing squad and

their bodies burned in a kiln. The photos were on the web site the same

day.

The

most dedicated and respected Cyber warrior in Kosovo today is a 33 year-old

Serbian Orthodox Monk, Father Sava Janjic. As the monks in medieval monasteries

once pioneered the use of the printing press, the Monastery in Decani,

built 663 years ago, sends out a steady stream of E-mail to promote peace

and conciliation in Kosovo. The old church contains the bones of Knights

who fought in the famous battle of Kosovo in 1389, but today it is the

home of a new breed of warrior, the Serbian Cyber-monk. Within a

few hundred yards of this ancient monastery is a wasteland of burned homes

and looted shops. Decani has seen a lot of fighting since the 14th century,

but none more devastating than in the summer of 1998 as Serb and Albanian

military groups fought it out and the mostly Albanian civilians ran for

their lives.

The

most dedicated and respected Cyber warrior in Kosovo today is a 33 year-old

Serbian Orthodox Monk, Father Sava Janjic. As the monks in medieval monasteries

once pioneered the use of the printing press, the Monastery in Decani,

built 663 years ago, sends out a steady stream of E-mail to promote peace

and conciliation in Kosovo. The old church contains the bones of Knights

who fought in the famous battle of Kosovo in 1389, but today it is the

home of a new breed of warrior, the Serbian Cyber-monk. Within a

few hundred yards of this ancient monastery is a wasteland of burned homes

and looted shops. Decani has seen a lot of fighting since the 14th century,

but none more devastating than in the summer of 1998 as Serb and Albanian

military groups fought it out and the mostly Albanian civilians ran for

their lives.