|

|

|

|

Claxton

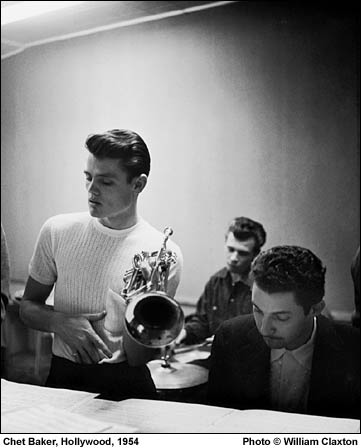

Interview: Chet Baker Jazz trumpeter Chet Baker taught me the true meaning of the term "photogenic." When I first started out, I met many beautiful girls and handsome guys and photographed them with less than happy results. Being pretty seemed to have little to do with it. Early on I learned that attractive people do not necessarily record well on film. I first met Chet in 1951. He was on a small bandstand at the Tiffany Club in Los Angeles with Charlie Parker and a group of mostly black musicians. Chet was pale white and yet had an athletic stance. He looked like an angelic boxer, a tough guy with a pretty face topped with a slick '50s pompadour. The truly odd thing about him was a missing front tooth which he tried to conceal. Later, when I got to know him better, he told me he did not want to have the tooth replaced because he was afraid that might change the sound of his trumpet playing. When I began printing the pictures of these jazzmen in my darkroom, it was Chet's image that came through in the developing tray as a spectacular young face. What a great-looking guy! He's better looking in the photograph than he is in person, I thought. A light bulb turned on above my head: So that's what being "photogenic" means. During this period, my friend Richard Bock formed Pacific Jazz Records, and Gerry Mulligan and Chet Baker became the label's big stars. Then Chet formed his own enormously successful quartet. I was fortunate to get to know him well (as well as anyone could, he was enigmatic). I photographed him during his rehearsals, recording sessions, and live performances and at early morning parties and jam sessions. After five or six years, Chet and I grew apart, partly because of his increasing use of drugs and his frequent incarcerations. He had to spend more and more time in Europe to avoid arrests in this country. One cold, wintery night in 1970 at Da Vinci Airport in Rome, I was seated reading a book while waiting for my delayed flight back to my home in London. Suddenly, I looked up from my book to see a figure coming toward me. In spite of the cold weather, he was dressed in blue jeans, a T-shirt, and sandals. He carried a trumpet case. "I don't believe it!" I thought to myself, "It's Chet." He looked dreadful and old beyond his years. As he approached me, he said casually and softly, "Hi, Clax, can you loan me sixty to get back to Amsterdam?" He was quite direct, no small talk, just his request. It was as though we had just seen each other the day before rather than some thirteen-odd years earlier. I tried to talk with him a little, but it was quite evident that he just wanted the money, forget the conversation. I did, of course, give him the money, and since it was cold, I gave him a sweater from my bag, which he accepted courteously. He promptly put the sweater on over his head and pulled it down. The odd thing was that I am very tall, and Chet was not. He looked hilarious in that big sweater hanging on him as he continued down the hall to the ticket counter. I didn't see Chet again until Bruce Weber brought us together when he was filming Let's Get Lost. Of course we both had aged, but Chet looked exceedingly old with heavy lines in his face, thinned hair, and no teeth. I was shocked. Just before Bruce's documentary about Chet was released, in 1983, Chet died in Amsterdam after a fall from the second-story window of a hotel in that city. The Dutch police concluded that it was an accident, but mystery still surrounds the circumstances of his death. |

|

ARCHIVES

| PORTFOLIOS

| LINKS |

Books

by William Claxton |

Send us your

Comments |