|

So, I turned my imagination north, resolving that one day I would fly about the Alaska Bush in my own plane. I would become intimate with the wilderness, and the people of the wilderness. In 1974, I married a woman belonging to Arizona's White Mountain Apache Tribe. Feeling the need to learn something of my wife's, and future children's heritage I postponed my long-held Alaska dream and took on the job of single-handedly producing the tribal newspaper, the Fort Apache Scout. In June of 1981, my wife and I sold the bulk of our possessions, packed what was left, and along with our three small sons and an infant daughter, piled into a Volkswagen Rabbit and hit the highway north.

In the hope of photographing the unique and fascinating life of the Iñupiat Eskimo and their bowhead whale hunt, I traveled to Barrow for the first time, in early May of 1982. Hunting conditions were perfect. A steady procession of bowheads blew their way through uiñiq -- the open lead of water that separates shore-fast ice from the constantly drifting polar pack. Yet, I found no one hunting whales. For millennia, the Iñupiat had hunted the bowhead with no interference from the outside world. The whale was the focal point of the Iñupiat's cultural, spiritual, economic and social life. But, in 1977, the International Whaling Organization, backed by the U.S. government, informed the Iñupiat that they could no longer hunt bowheads, thus bring their sacred culture and way of life to an end. IWC based this moratorium on marginally accurate scientific data. It indicated that the bowhead population, estimated to have numbered about 20,000 animals in the mid-nineteenth century, before the coming of the Yankee whalers, was now as low as 600, and could sustain no further hunting. Iñupiat hunters countered that the bowhead population numbered many thousands, and was growing, not being depleted. IWC and the U.S. discounted the Iñupiat's numbers as non-scientific and totally wrong. In response, the hunters formed the Alaska Eskimo Whaling Commission. By whatever means necessary, the AEWC members traveled to London, Tokyo, Washington, D.C., or wherever IWC and U.S. government officials connected to the moratorium could be found. They argued their case with force, and succeeded in winning only a small, insufficient quota--12 bowheads--for the entire Alaska whaling community, spread along 1,500 miles of Arctic coastline. They did, however, also persuaded the government to fund a long term, in-depth whale census. AEWC struck a cooperative management agreement with the federal government, under which the hunters agreed to honor the quota and enforce its terms upon their own people, provided the IWC and the U.S. would revisit quotas should whale numbers prove greater than scientists originally believed.

As a white journalist, I was greeted with anger and hostility. I hung on, though, and did the best job I could. By May of 1985, I had left the Tundra Times to freelance. I returned to Barrow and was taken in by the crew of George Ahmaogak. Heavy ice conditions prevailed and kept the lead closed for the most part. During the 12 days I spent with Ahmaogak, we saw only one whale, breaching through a crack in the mirage zone, far beyond our reach. In the fall of that year, with funding from the North Slope Borough, I founded Uiñiq, a one-man-magazine dedicated to covering the community life of the Iñupiat. For about the same price as a good used truck, I purchased a 13-year-old spruce-framed, fabric-covered airplane and named it Running Dog. I used Running Dog to travel back and forth between my family in Wasilla--700 nautical miles south of Barrow -- and the nine villages of the Utah-sized borough. I made forays on and off the ice, helping whatever whaling crew I had tagged up with, in whatever way I could. To earn my place in camp, I often had to put down my cameras and take up a pickax to cut trail, or to perform the countless tasks assigned to young boys. My eyes saw many photos I could not take. After a tremendous amount of work, clearing the way, whales would begin to appear, and then, before the opportunity to strike, we would learn the quota had been filled elsewhere on the lead. We would pull back, then hear other reports about a village further up the migration route that had given one of their allotted strikes to Barrow. So, back out we would go. Just as the crew had again made everything ready, and it seemed certain a whale would soon present itself, a strike would be made elsewhere. Frustrated again, we would pull off the ice.

Aboriginal whaling presents modern day America with a dilemma. This is supposed to be a time when America is recognizing the wrongs it perpetrated upon its native peoples and trying to right those wrongs where ever possible. Many claim a desire to adopt the native values, of living close to nature and cherishing the environment. For native peoples, this has always meant taking wild animals and using them for food, for culture, for economics, and for spirituality--whether they are deer, buffalo, salmon, or the whales of Alaska. I found the hunt to be a wonderful experience. The whale brings much good to the people who hunt it, both physically and spiritually. From the beginning, the whale allowed the first people to thrive in Arctic Alaska. Even today, the best of Arctic Alaskan traditions and activities found here are based on the hunting and sharing of the whale. |

|

|

|

| Buy the book from our partner, Barnes and Noble | |

|

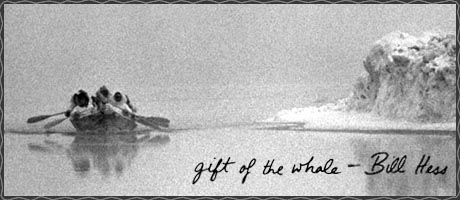

GIFT

OF THE WHALE; THE INUPIAT BOWHEAD HUNT, A SACRED TRADITION

by Bill Hess Price: $28.00 Retail Price: $40.00 You Save: $12.00 (30%) Format: Hardcover, 256pp. ISBN: 1570611637 Publisher: Sasquatch Books Pub. Date: September 1999 |

| PAGE

1 | 2

| 3 | 4

| 5 | 6

| 7 | 8

| 9

| 10 | 11

| 12

13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 | 31 | 32 | 33 | 34 | 35 VIEW THE INDEX PAGE |

| Contents | Editorials | The Platypus | Links | Copyright |

| Portfolios | Camera Corner | War Stories | Dirck's Gallery | Comments |

| Issue Archives | Columns | Forums | Mailing List | E-mail The DJ |