I

remember hearing stories my mother told me about dangerous political times

in China, first during the Japanese occupation of China and World

War II, and then after the revolution led by Mao Tse-tung.

Her account seemed so oddly nonchalant (maybe she did not want to remember;

maybe she did not want to burden me) that the stories felt as if they were

about someone else. I

remember hearing stories my mother told me about dangerous political times

in China, first during the Japanese occupation of China and World

War II, and then after the revolution led by Mao Tse-tung.

Her account seemed so oddly nonchalant (maybe she did not want to remember;

maybe she did not want to burden me) that the stories felt as if they were

about someone else.

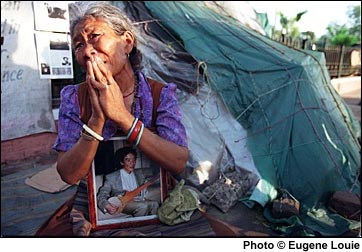

It wasnít until I met Sonam Dekyi

on the streets of New Delhi, India, did I learned the true nature of political

oppression. Dekyi is the mother of imprisoned musician Ngawang Choephel,

a Fulbright scholar who had journeyed back to his native Tibet to video-tape

traditional Tibetan music and culture.

Her son was reported missing in Tibet

in August 1995. Dekyi waited 14 months to discover he was still

alive, but that he had been jailed in a Chinese prison in Tibet on

charges of espionage. He is accused of spying on behalf of Tibet's

exiled leader, the Dalai Lama and "a certain foreign country" -- apparently

an allusion to the United States.

Since then, the 62-year-old Dekyi has

campaigned continuously for the right to see her son. Her fight has

attracted global attention; thousands of appeals have been forwarded to

Chinese authorities. Hunger strikes were begun in Ngawang Choephel's

name. All are met with silence.

Hansa Natola, an Italian supporter

of the hunger strikers, introduced me to Dekyi, who was sitting alone

on Parliament Street, handing out petitions and leaflets in English

and Hindi, flanked by a crude lean-to tent that faced the luxurious Park

Hotel.

Dekyi left her home in Mundgod, in southern

India, last June and began living on the streets of the capital, appealing

to anyone who would listen for her son's release. She pulled out an 8"

x 10" color photograph of him to show me, wrapped her arms around

the frame, pressed against herself and began to cry, explaining the details

of his arrest. Natola and I soon began to call her "Mom," and paused

daily to greet her in the traditional Tibetan way of putting your hands

together as in prayer and saying, Tashi Deleg - good day.

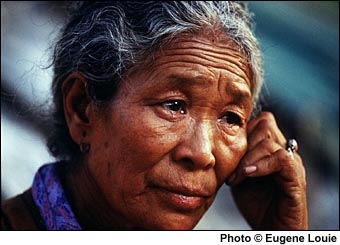

In many ways, Dekyi's facial features reminded

me of my mother's. After I finished photographing her nightly candlelight

vigil I put down my cameras, sat down with her and massaged her back.

Even though we had no common language, "Mom" held her hand up in front

of her, as if she were praying, letting out a sigh of relief

each time I loosened a particularly tight muscle.

During her effort to find her son Dekyi

contracted tuberculosis, but she discounts her health problems, saying

she is an old woman who only wants to "meet my son one last time before

I die".

While researching the Tibetan hunger strike

in the United States on the Internet I learned more: Years ago, this

mother had escaped Chinese brutality carrying two-year-old Ngawang on her

back over the Himalayas to freedom in India. Dekyi devoted her life

to caring for and educating her only child in a Tibetan refugee camp.

Her efforts paid off; Ngawang's passion for Tibetan arts surfaced

in elementary school. He taught music at the Tibetan Institute for

the Performing Arts in Dharamsala. Later, he earned the prestigious

Fulbright scholarship to study ethnomusicology in the United States at

Middlebury College in Vermont.

Ngawang always felt a duty to preserve

the cultural identity of Tibet through its music and performing arts.

At 30, without telling his mother, he armed himself with a video camera

and tape recorder and entered Tibet, knowing a returning Tibetan exile

could be imprisoned on the slightest provocation.

Before Ngawang's arrest he gave his video

tapes from two months of travel to an American traveler, fearing they would

be confiscated if they were found in his position. The tapes show

old men on mountain tops performing opera to the wind, little girls singing

nursery rhymes and lamas doing wrathful dances to chase off demons.

"In 16 hours of Mr. Choephel's video footage,

not a single scene exists indicating that he was involved in any political

activity whatsoever. His extensive photographic record shows he was solely

engaged in cultural documentation," according to John Ackerly, president

of the International Campaign For Tibet in Washington, D.C. (http://www.savetibet.org)

See the RealVideo of Sonam Dekyi,

produced by Ruthie

Ristich.

Click on the appropriate

modem speed:

28.8K

56.6K

High-Band

After I left India, Notala and I conducted

a long - distance interview of Dekyi: Natola asked the questions

of Dekyi through a translator, then e-mailed the results to me in

the United States. Here is our conversation. Parliament Street,

New Delhi, India, May 3, 1998

Q:

Why did you decide to leave your home and come to Delhi to live on the

street? Q:

Why did you decide to leave your home and come to Delhi to live on the

street?

A: The reason I came here to Delhi is

that my son, who is a musician, was studying music in Tibet, and the Chinese

caught him and imprisoned him, giving him a sentence of 18 years. Now I

have totally decided to leave my home and protest here. I would like the

Chinese to release him immediately. If not, I would like them to

allow me to visit him. The only thing I know is that I am now 62-years-old

and I am suffering from tuberculosis and I know that I donít have many

years to live. I also know that my son is totally innocent, the only

thing he was doing was Tibetan music, thatís all.

Q: Why this specific spot?

A: The reason I am here is that this is

a place where all people from all over the world come. In this particular

street I would like to appeal to every single person who comes here to

help me to get the Chinese to release him, or for me to meet him. I would

like permission from the Chinese government to meet my son who is innocent.

Q: I read in your appeal that you actually

went to the Chinese Embassy here to ask for a visa to enter Tibet, but

they told you to wait. Have you received a reply?

A: I went to the embassy in January 1996

and I met a tall looking person there and I asked him if he could give

me permission to visit my son. What he said is that I would have to wait

4 or 5 months. After that he would give me the permission. Since then,

I went back at least three times, and the last time I went was in August

1997, and again there was no word from them.

Q: Did you visit the Embassy alone or did

you go with someone?

A: The first time I went to the Embassy

there were three people helping me. The second time I went alone, and the

last time I went with my brother.

Q: What do you do with the petitions that

people sign?

A: I plan to offer them to the United

Nations.

Q: How many pages have you collected so

far?

A: About one thousand.

Q: How long are you going to wait before

you present them to the United Nations?

A: I have been collecting these petitions

for almost one year. I am now planning to wait one, or two months, and

then present them to the U.N.

Q: Do you know whom to approach at the

United Nations?

A: I donít know whom I should be presenting

them to, but I plan to be taking the assistance of Indian, as well as Tibetan,

well wishers here.

Q: How long do you think you will live

here on the pavement?

A: I plan to stay here on the street until

some fruit comes out of this effort I am making;. Until my son is released

by the Chinese.

Q: Would you accept some kind of promise

from the Chinese government that your son will be released soon?

A: I cannot trust them 100%, so until

my son is really released I will not accept any promises. Only the day

when he is really released will I leave this place.

Q: There are many associations all over

the world who are working on your case. Are you in touch with any of them?

A: So far, I have no real relation

with any of these organizations. I am not able to know who is fighting

for him or not. As far as I am concerned, I believe that human beings out

of compassion will contact me and help a mother who has lost her son. From

my side, I am illiterate and I donít know how this functions and which

organization is working to release my son. I have no idea, not even how

I should contact these people. I am sure that people all over the

world are willing to help me out of compassion, out of kindness, out of

love, thatís why I am here on the street appealing to people. I believe

there are organizations attempting to help, but as far as I can see

there is no organization anywhere in the world who can even tell me where

my son is imprisoned, in which part of Tibet he is, or whether he is already

dead. If an organization can at least pinpoint that much, then probably

I would believe that there are organizations which are helping in this

issue. Until then, I know that I am an individual who is trying to get

my son released, thatís all.

Q: How do you survive living in the streets

in New Delhi? How do you get money?

A: In the past, for many years when my

son was alive and working, in India or in the United States, I lived off

him because my health is bad. I always lived on his earnings. Now

that I have come on the street...things are a little difficult, and so

I have gone to the Tibetan welfare officer in Majnu Ka Tilla in Old Delhi,

and I have received aid from him twice in the last two years for a total

of 1,700 rupees (about $42.50 US). With this money I actually can last

for quite a long time if it was just a question of getting something to

eat. I can live on 500 rupees a month (about $12.50 US). My expenditures

are mainly for the paper for the petitions, which cost quite a lot of money.

I also receive money from well wishers, and as a result I am alive. I have

enough money to eat and pay for the petition papers. The day I will not

have enough money I will go again to the Tibetan welfare officer, but recently

I have had no need to go back to him. Also I have received some money from

an Italian girl. She sent 1,500 rupees. Money will come.

That finance is difficult is just normal. I donít consider that as

an additional burden whatsoever.

Q: If you stay here much longer you

might die and then never meet your son again. How can we convince

you that your son will be released one day and that you might have to practice

a little more patience? This could save your life and your son could

also enjoy being with you again one day.

A: If all these organizations you

have been talking about will really help me to get my son released soon,

then I think I will be able to wait, whether here or anywhere else. But

if it is going to take interminably long then there is nothing really that

I can do. And then I think that I will also think of some more severe

desperate measures... When I lose faith completely that I don't think I

will meet my son this life, then I will commit suicide. But as far as where

I will do it, I will think about it and I will do it at the appropriate

place.

Q: Is there something specific you would

like to say to anyone who reads your story?

A: I appeal to the compassion of everyone

all over the world to help a single mother to get her son released from

the Chinese government. I am sure that you know better than me whom

to appeal to, to your representatives, to your governments. These

are things that myself, an uneducated, illiterate old Tibetan woman, has

no idea of. And I just pray that all of you, people who have

been so helpful, might live forever.

Eugene Louie can be reached at: elouie@sjm.infi.net

San Jose Mercury News, 408-271-3660 |